British filmmaker Mike Leigh is known for his unusual directorial techniques. Using improvisation to shape his characters, dialogues, and storylines, Leigh usually begins his films with a rough outline of possible thematic directions and plot developments. Choosing not the disclose any information regarding plot or character to his cast members, Leigh introduces the actors to each other in the order in which they would normally appear in the film. The actors are then told to stay in character in order to discover their innermost motivations, preoccupations, and responses to external stimuli. Once this stage is completed, after weeks of improvisation work, the cast may start shooting, having acquired in this way a comprehensive understanding of their characters and each other.

Acknowledging the playwright Harold Pinter as an important influence, Leigh usually inscribes within his characters some kind of muted struggle and a failure to express deep-rooted conflicts, often related to the incapacitating realities of British working class family life under Thatcher. Very bleak, Leigh’s kitchen-sink dramas cut to the core, as the filmmaker strives to document the lives and voices of a much-overlooked segment of British society.

Family secrets, ultra-violence, brutal dialogues, and sadism frequently feature as part of Leigh’s cinema. Often compared to the Japanese filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu, Leigh’s films provide a unique and compelling perspective on the institution of the family and the various social ties born within underprivileged East London homes.

10. Happy-Go-Lucky (2008)

Marking a curious departure from Leigh’s earlier films, Happy-Go-Lucky rejoices in the simple pleasures of every-day life. A celebration of contentment and joie-de-vivre, Leigh’s film follows Poppy (Sally Hawkins), a thirty-year-old primary school teacher, with a happy disposition and a can-do attitude. Whilst Poppy’s depressing environment and relatives threaten to imperil her positivity, the young teacher remains light-hearted, displaying an indestructible cheerfulness and an astonishing amount of empathy for others.

Do not expect any underlying sarcasm or chaos from Happy-Go-Lucky, as Leigh described his work as an ‘anti-miserabilist film’, thence denying allegations to any deeper, darker, unspoken side to Poppy’s character. Arguably the least representative film in Mike Leigh’s filmography, Happy-Go-Lucky is, albeit a bit of an outlier, a pleasant and relatable comedy with an uplifting message. Less fiercely militant than Leigh’s older films, Happy-Go-Lucky does not feature any of Leigh’s signature anti-Thatcherian political commitment, which made Secrets and Lies and Life is Sweet so compelling. With Happy-Go-Lucky, in fact, Leigh achieves the difficult feat of retaining the quick affect of his style, in a Blairian, post-Thatcher landscape.

9. Another Year (2010)

An intimate look at the psychologies and experiences of ordinary people through the course of one year, Another Year is an ensemble drama, very characteristic of Leigh’s later cinema, which dives into the every-day lives of a married couple, geologist Tom and NHS counsellor Gerry, and their unhappy single friends, Mary and Ken. Combining comedy with tragedy, Another Year pits Tom and Gerry’s happy contentment against the harsh realities of their friends’ unbridled solitude. Starring some of Leigh’s favoured actors, such as Jim Broadbent and Ruth Sheen, this family drama is sectioned in four parts, according to the seasons, as it examines the quiet ebb-and-flow of life, narrating in this way the gradual passing of time within the space of middle-class, middle-aged Britain.

Described by Leigh as ‘a very personal film’, Another Year represents a return in tone and theme to Leigh’s older films following the success of his romantic comedy Happy-Go-Lucky. An exploration of memory, family, relationships, and personal failures, Another Year offers a bittersweet portrait of the lives of the 50+, as it is set upon finding the sublime within the small, matter-of-fact elements of daily life, very much in the tradition of Ozu’s cinema.

8. Life is Sweet (1990)

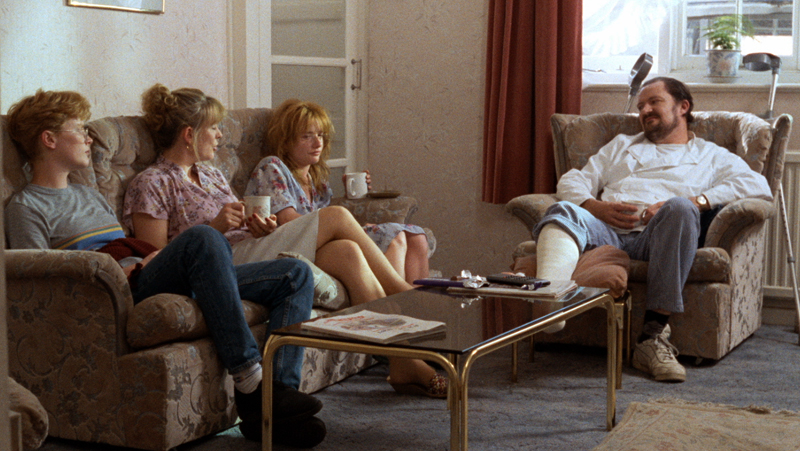

Starring Leigh old-timers Timothy Spall and Jim Broadbent, Life is Sweet enters the home of a working class family settled in suburban North London over a few weeks during the summer. Life is Sweet follows Wendy, a part-time waitress, and her husband Andy, a senior chef working for a company of London caterers, as well as their two daughters, the twins Nicola and Natalie. Whilst practical, down-to-earth Natalie works as a plumber’s mate, Nicola suffers from bulimia and deep-seated unresolved issues related to her very troubled and guarded rapports and relationships, as well as her weight, and appearance.

An ensemble dramatic comedy, very much à la Mike Leigh, Life is Sweet looks at the smaller things of life, focusing on the dynamics of every-day family situations, as its fully rounded, lifelike characters attempt to negotiate their own unresolved issues, seeking some kind of redemption against the bleak climate of working class suburban London. Similarly to Poppy, Wendy persists in looking at the glass half full, as she resolutely strives to nurture happiness and contentment within her family and home.

7. Vera Drake (2004)

Vera Drake is a period drama set in the fifties, which tells the tale of Vera (Imelda Stauton), a benevolent working-class mother and wife, who performs backroom abortions, free of charge, to help distressed young women burdened by unwanted pregnancies. The abortionist, however, finds her altruistic activities to backfire when an abortion goes wrong and the authorities finally catch her out.

Intended to instigate debate on the controverted topic, Vera Drake assumes a non-judgemental attitude on the subject of abortion. Placing Vera’s feminine philanthropy against the law, Vera Drake questions the sanctity of national codes of conduct and established social order.

Set in an austere Post-War England, Vera Drake also interconnects issues of class and ethics. Whilst working-class pregnant women were left to their own devices, wealthier women were provided other options, Leigh argues with the example of Susan’s character, a privileged young lady who is able to terminate an unwanted pregnancy legally at a clinic thanks to a costly sum.

6. Meantime (1984)

Featuring the dazzling performances of award-winning actors Tim Roth and Gary Oldman, this drama introduces Oldman to the public, also serving as a prime example of Mike Leigh at his best, as it explores the meandering lives of working-class youths during the political and socio-economic wasteland of Thatcher’s premiership.

With a very simple plot, Meantime relies on quick-paced, often violent dialogue, as it follows a family’s two unemployed sons, Colin, a reserved and sensitive teenager, and Mark, his outspoken, very loud brother. The pace picks up, and family rivalry ensues when Colin is offered a work opportunity by the family’s richer relative, Barbara, and Mark isn’t.

A gritty sketch of unemployed dejected youths during the time of Thatcher’s rule, Meantime reflects on the importance of focus and ambition, as it depicts the struggles faced by young people left to their own device in a London, which failed to promise them a future. A heart-breaking family drama, Meantime introduces some of Leigh’s signature directorial moves and thematic preoccupations.