When explaining why he dropped out of film school, Paul Thomas Anderson said “My film making education consisted of finding out what filmmakers I liked were watching, then seeing those films. I learned the technical stuff from books and mags…Film school is a complete con, because the information is out there is you want it.” Whatever ones motivation, the joy of uncovering the lineage of a favorite director by watching the films that inspired him or her adds another layer of pleasure to the pursuit of excellent movies. To that end, let’s look at the unofficial ancestors: a list of films that influenced great directors.

Wes Anderson is unafraid of riffing on iconic films and personal favorites. His films have film history lovingly woven into the story, dialog, mise-en-scene, and musical score. Most of his scripts are originals written by himself and a partner or two. Books are a key source of inspiration, but there are a few films, some famous some not, that stand out as representative influences that coalesce to make the Wes Anderson style complete.

1. Les Quatre Cents Coups (1960, Francois Truffaut)

In the world of Wes Anderson, any list of influential films must begin with Les Quatre Cents Coups. Wes Anderson called this the film that made him want to be a director. Francois Truffaut broke ground ready to be cultivated by future generations of auteurs with this loosely told tale of a troubled child, based on his own youth.

As one of the Cahiers du Cinema writers and reviewers, Francois Truffaut was part of a movement of critics who detested the state-sanctioned films of France—what he called the Cinema of Quality which relied on the legacy of high literature for its inspiration. Their collective musing became the auteur theory, the prevailing explanation as to how certain directors working within a studio system aimed at standardization still managed to have a distinctive style all their own.

When it came time for Truffaut to make his debut film, he took permission from the Italian Neorealists to employ non-professional actors and on-location sets. He did not want a story with an Aristotelian arc, nor did he want to conceal any of the artifice of film as is the goal of traditional editing procedures. The result is a evocative story of a boy getting shunted into manhood by a variety of incidences that leave the audience unsure as to the character’s fate.

The child star, Jean-Pierre Léaud, is so genuine as the unhappy Antoine Doinel—see the series of monologues he gives near the end of the film, explaining himself to a child psychologist at an institution for troubled minors—that Truffaut worked with the actor on six more pictures over the next 20 years. Four of those six were reprises of Antoine Doinel, at different life stages.

The film that kick started the Nouvelle Vague movement is to be found in many a contemporary director’s list of influences but in the films of Wes Anderson we see a particular debt being leveraged masterfully. Like the Truffaut-Léaud creative partnership, Wes Anderson discovered Jason Schwartzman when looking for his stand-in for a troubled youth re-imagined as the film Rushmore. Shot at Anderson’s alma mater, St. John’s School in Huston Texas, Rushmore was Anderson’s first commercial success and the first of several pictures to include Jason Schwartzman.

Truffaut and Anderson are always after some ineffable feeling, using all the tools available in the medium of film to evoke it. Both films employ the holiday blues in key transitions. Les Quatre Cent Coup happens over the Christmas season and we spot drab decorations in the background but get no hysteric demonstrations (“How could you steal your step-father’s typewriter? And on Christmas Eve!”). Rushmore is spread out over several months, but in the December sequence a Christmas depression hangs heavy for Max who has been expelled from Rushmore Academy.

The world is a little cold towards its protagonists, indifferent to their pain. But Wes Anderson brings a contemporary flair to this influence. Les Quatre Cents Coups is a rebellious film, but in our less innocent age we are taken in by the innocence behind the rebellion, and this self-conscious quality gets transposed to great comic effect. For example, the montage of The Royal Tenenbaums and Ari and Uzi out on the town, or when we see the nudes in Moonrise Kingdom that Sam paints. Wes Anderson is often criticized for being twee but really he’s staying true to that cinematic experience of witnessing rebellion with just enough distance, just enough amusement, and understanding. For both directors, no failing in their characters is without understanding.

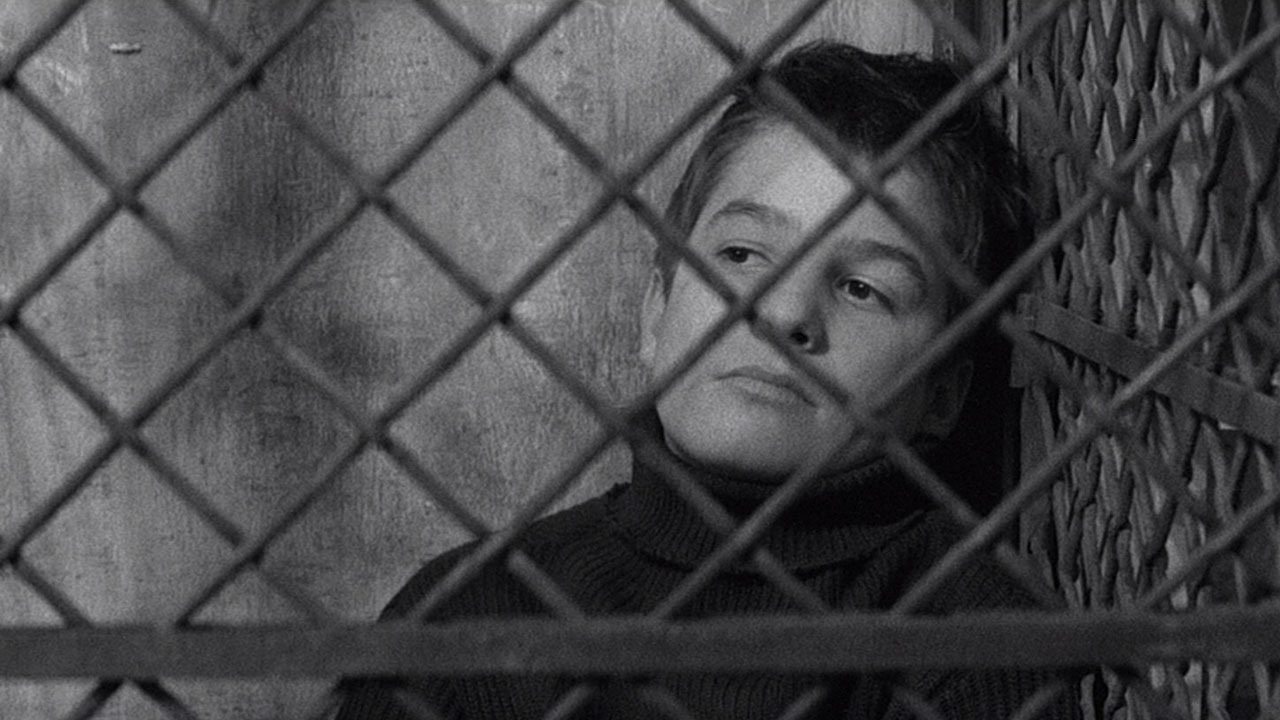

Les Quatre Cents Coups is an enduring influence and anchor point of style for Wes Anderson. If there is a primary difference it can be best exemplified by the scene where Antoine Doinel sits in his cage at the police station and pulls his turtleneck over his mouth and crosses his arms. He is both protective of his inner secrets and putting on a personalized gesture of defiance. Compare to the scene in The Darjeeling Limited when Francis Whitman (Owen Wilson) removes his bandages. The exposure neither conceals vulnerability nor signals a hardening will. Instead, vulnerability is put front and center, the aftermath of a gesture of defiance. Where Francois Truffaut is elusive and unyielding, Wes Anderson would rather be blunt and guileless.

2. Lola (1961, Jacques Demy)

Written as a tribute to another Anderson influence, Max Ophüls whose La Ronde uses tracking shots that will be familiar to any Wes Anderson fan and whose Letter from an Unknown Woman is based on a Stefan Zweig novella much like The Grande Budapest Hotel, Jacques Demy’s debut was conceived as “a musical without music”. He would go on to greater fame for making musicals with music like The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, but here in Lola there is much to be admired musically. Nobody sings their thoughts and feelings, but the eponymous character is a singer in a nightclub who likes to occasionally sleep with sailors who frequent the club while their ships are in harbor. This is another first film with autobiographical ties. It is set on the French Atlantic coast, Jacques Demy’s place of origin.

Dealing with the crisscrossing paths of lovers and friends, Lola has the cozy feel of an ensemble cast in a self-contained world. There is a restless, begrudged man trying to get his bearings in the adult world. A young girl enchanted by comic books who runs away from her single mother. An American sailor who slaughters the French language endearingly with his accent. And a mysterious gentleman, bedecked in white suit, Stetson hat, smoking a cigar and driving a white Cadillac, who is revealed to be the long-missing lover of Lola and her child’s father. And at the center of it all is Lola: adorable, talented but going nowhere, deeply sad. She has been ruined by love and makes the best of it.

If you really want to see where Wes Anderson learned to saturate his scenes with the rich magic of cinema – those iconic and often parodied slow-motion scenes filled with music – then look no further than the carnival in Lola, where the American sailor gives the young girl her first kiss and soon thereafter lifts her out of the ride.

The kiss is concealed, and in a way inessential. What carries the impact of this girl’s initiation into the adult world of love is that lift: masculine, reliable (for the moment), and yet fatherly. She is fatherless, and in the act of kissing a sailor (as her mother did before her, we learn later) that pain is made unbearable sweet. The hand of fate is gentle with these characters, and fate will continue to be a theme for Jacques Demy.

3. Tokyo Story (1953, Yasujiro Ozu)

Any one of the films by Japan’s Ozu could be this example because literally every film he made that survived the bombings of WWII, and everything after, is the same film. A middle class family struggles to come to grips with one another and the beautiful melancholy of the passage of time…in minutely arranged mise-en-scene.

Ozu is one of the names never associated with Anderson and that’s a baffling oversight. Perhaps it is because Yasujiro Ozu is so very Japanese. Tokyo Story is on this list because Wes Anderson would certainly have seen it, but Early Spring is a great contender for anyone looking to get a sense of Ozu’s haiku-like films. Tokyo Story follows two elderly people on their trip to Tokyo to visit their children, see their grandchildren, and have their expectations disappointed. The son who is supposed to be a distinguished doctor is a lowly neighborhood general physician. The younger son keeps away, obsessed with baseball and his career. The daughter’s children are brats, and the ill-tempered daughter only exerts herself to get her parents out of her house. They are carted off to a hot spring resort, where they cannot sleep, and the only person who is truly appreciative of their presence is the widow of their son who died in the war.

Ozu is most famous for a particular camera angle that he used in all his interiors. three feet off the ground, angled slightly up. The effect is said to replicate the view one would have from a tami mat on the floor, as if you were a guest in the home of the family. Take your pick of any supercut available on the internet that examines Wes Anderson’s own idiosyncratic framing practices. But beyond the idiosyncrasies, Ozu displays a rigor in the way things are arranged. His actors used to report that they were used like puppets, and the results were so good that they dared not interfere with the master’s vision.

The case can be made that WA learned the bliss of trademark camera choices and obsessive attention to detail from Stanley Kubrick (our next entry), whom he has publicly mentioned as an influence, but taken with the melancholy tone of Ozu’s filmography anyone who wants to watch the films that influenced Wes Anderson could do little better than exploring the work of Yasujiro Ozu .

4. Barry Lyndon (1975, Stanley Kubrick)

One of Stanley Kubrick’s least successful films, Barry Lyndon is an adaptation of a novel by William Makepeace Thackeray detailing the rise and fall of an Irish ne’er do well in the time of George the Third. The title character has several turns of fortune, from fugitive to soldier to spy to gambler to lord to fugitive again. All the while Kubrick employs a cool distance so that his audience is not instructed to empathize too greatly.

Like many of Anderson’s characters, Barry Lyndon is self-interested, none too clever, but talented. What makes this Kubrick film more influential is its use of Brechtian distancing. There is an artificial quality to the acting that Wes Anderson has used to comic effect in several scenes of his movies. The most consistent being The Darjeeling Limited where the actors’ timing is deliberately off, though it is more precise that the extra 2 seconds between set-up and punch line one gets in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou.

Another quality that’s made to distance the audience from the action by making it seem less real, is the choice of language. Barry Lyndon is set in a different time, and is based on a novel that is unafraid of high diction and sentimentalism. Kubrick’s genius is in neither updating the way people talk to one another nor forcing it to seem natural.

For example, when Barry Lyndon’s spoiled son falls off the horse that was to be his birthday present, distress is performed as if the characters are aware of an audience. Neither natural grief nor frantic editing assist the viewer in feeling what the characters feel. Instead we are kept at a distance, to judge as we please the goings-on.

Wes Anderson is equally unafraid of unnatural dialog and interactions. Whenever Royal speaks to his children as a group, the patriarchal Tenenbaum is keenly aware of his presentation, choosing words and expressions to make a sentimental impression, though we are quick to learn that he is far from being a sentimentalist. There is a consciously by-golly midcentury style to the dialog in Moonrise Kingdom too.

5. A Charlie Brown Christmas (1965, Bill Melendez)

The perennial Christmas TV special is hardly an influence from film school. Wes Anderson once said in an interview, “If I had to list my top three influences as a filmmaker, I’d have to say they are Francois Truffaut, Orson Welles, and Bill Melendez.” How has Melendez’s A Charlie Brown Christmas influenced Wes Anderson? Many of his films borrowed music from the soundtrack of A Charlie Brown Christmas. In his more recent movies, he’s cut loose with goofy antics and cartoonish tropes, like the lightning strike in Moonrise Kingdom.

Like Melendez (and Charles Schultz, author of the Peanuts comic strip) Wes Anderson meets his child characters were they are. Their concerns are never condescended to; rather, it is their travails he treats most seriously. Childhood is serious business for children, whether the children in question are orphans (like Sam Shakusky in Moonrise Kingdom), or grown children (like Mr. Blume in Rushmore).

Another aesthetic heritage from A Charlie Brown Christmas that shows most strongly in The Fantastic Mister Fox is roughness. The animation was considered sub-par even by 1965 standards. The audio was messy. One 3 of the child voice actors had any prior experience and the girl voicing Sally, Charlie Brown’s sister, couldn’t read. The jazz soundtrack was jarringly different than studio executive expectations and the whole thing was expected to flop. Instead it captured 50% of all television in the USA when it aired, launched the Peanuts series of feature films and specials, and has become a holiday tradition.

And so, in the age of pristine 3D modeling and computer wonder (think Pixar), Wes Anderson was unafraid to make a feature length film using techniques that made the 1933 King Kong a smash hit. Perhaps we should have anticipated it when watching the clearly manmade, unrealistic sea life in The Life Aquatic.