8. Marcelino pan y vino (Dir. Ladislao Vajda, 1955)

Marcelino pan y vino (The Miracle of Marcelino) is a nostalgic entry in this list. It tells the story of an orphan named Marcelino (Pablito Calvo) who sees and talks to Jesus in the attic of a monastery. The melodramatic story leads to a tearful climax in which (Spoiler Alert) Marcelino asks Jesus to let him see his mother, resulting in Marcelino’s death.

The film harnesses the power of melodrama, using its overtly religious themes to cross international boundaries. At the time, it was one of Spain’s most successful feature films in the international film market.

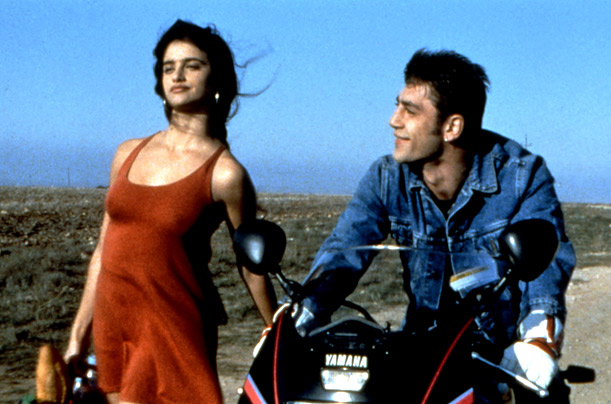

7. Jamon, jamon (Dir. Bigas Luna, 1992)

Bigas Luna’s Jamon, jamon (Ham, Ham) is an intriguing look at the conflicting identities of contemporary Spain. Silvia (Penelope Cruz) and José Luis (Jordi Molla) are in love, but José Luis’ overbearing mother (Stefania Sandrelli) doesn’t approve of the union. Utilizing all the tricks of her trade, the mother will stop at nothing to destroy her son’s union.

Jamon, jamon plays with cultural stereotypes and cultural expectations, leading to a finale that involves themes of sex, blood, violence, and legs of ham.

6. Hable con ella (Dir. Pedro Almodóvar, 2002)

Hable con ella (Talk to Her) showcases all of Almodóvar’s masterful talents. Following two comatose women and the men who care for them, Almodovar makes a gestural film that explores body language – examining Pina Bausch’s Café Muëller and silent films – as well as gendered roles – Lydia (Rosario Flores) is a female matador while Benigno (Javier Cámara) is a nurse. The film is sublime, weaving a tapestry worthy of bearing the moniker “A film by Almodóvar.”

5. Muerte de un ciclista (Dir. Juan Antonio Bardem, 1955)

In 1955, Juan Antonio Bardem used the Salamanca Congress to discuss the state of Spanish cinema. His assessment was that Spanish films did not represent the truth about Spanish life, in any way shape or form, and that such movements as Italian Neorealism tapped into the topicality of daily life.

Enter Bardem’s Muerte de un ciclista (Death of a Cyclist), released in 1955. Death of a Cyclist tells the ill-fated story of two adulterous lovers whose accidental manslaughter of the titular cyclist (who is neither seen nor heard) becomes their undoing. Bardem brilliantly oscillates between genres, harnessing the power of melodrama, neorealism, and thrillers to critique the elitist bourgeois culture.

4. Viridiana (Dir. Luis Buñuel, 1961)

Buñuel’s first Spanish film in years was meant to be a triumphant return to his home country after his exile…but like any Buñuel film there was controversy.

Viridiana (Silvia Pinal) is an aspiring nun who, before she takes her vows, decides to stay with her uncle, Don Jaime (Fernando Rey). Her uncle’s necrophiliac tendencies lead to a tumultuous journey including a wild dinner party, many instances of attempted rape, and a “three-way” card game.

Spanish officials, though hesitant of the controversial material, still claimed it as a “Spanish” film, until a denouncement from the Vatican led to Viridiana suddenly being banned in its home country.

3. Bienvenido Mr. Marshall (Dir. Luis Garcia Berlanga, 1953)

Coming out of the early years of the Franco regime, Berlanga’s Bienvenido Mr. Marshall (Welcome, Mr. Marshall) is an intriguing look at cultural exploitation as performance for foreign consumption. Upon hearing that American officials are arriving, a small Spanish village dons Spanish stereotypes in order to appease their foreign guests (and benefit from the Marshall Plan).

The film challenges the notion of an unadulterated culture, especially one that is hermetically sealed from the globalized market. Matters are complicated further when the characters themselves begin to dream in stereotypes about American culture.

2. Cria Cuervos (Dir. Carlos Saura, 1976)

Saura’s political allegories reached their peak with Cria Cuervos (Raise Ravens). The film follows Ana (Ana Torrent), a young child who “kills” her militaristic father out of vengeance for her deceased mother. Saura’s masterful storytelling paints a contemporaneous portrait of Spain in the 70s.

The title of the film derives from a Spanish proverb, “Raise ravens and they’ll peck your eyes out,” using the children in the film as a metaphor for the younger generation of Spaniards. Franco was dying during the production of Cria Cuervos, making the film a subtle reminder of the resentment the new Spanish generations would hold toward their oppressor.

1. El espiritu de la colmena (Dir. Victor Erice, 1973)

Along with introducing the world to the big black eyes of Ana Torrent, Victor Erice’s El espiritu de la colmena (The Spirit of the Beehive) is one of the best Spanish films ever made. A young girl named Ana (Ana Torrent) is so amazed by a recent screening of Frankenstein that she goes out searching for the monster. Along the way, she discovers a wounded Republican soldier, whom she cares for and feeds.

The film is elegant, sprawling the narrative trajectory across a vast and open landscape. And the images are so iconic that Ana Torrent recreated them for the poster of the 2003 San Sebastian Film Festival.

Author Bio: Jose Gallegos is an aspiring filmmaker with a B.A. in Film Production/French from USC and an M.A. in Cinema, Media Studies from UCLA. His main interests are the French New Wave, Left Bank Cinema, and Spanish Cinema under Franco. You can read his film reviews at nextprojection.com and view his film poster collections at discreetcharmsandobscureobjects.blogspot.com.