Like novels, plays, and other forms of art, movies sometimes have a lot more going on beneath their surfaces than it would seem. Writers and directors have often used the medium not just to tell stories, but to make moral or political points, and sometimes it’s this latter goal that’s actually the primary intention motivating a project’s inception.

The following list will examine movies that not only have deeper meanings, but that have gone out of their way to be subtle about them. For that reason, movies widely regarded as allegories, like The Crucible, will not appear here. Nor will metaphoric films that are particularly obvious (not that that’s necessarily a bad thing) about their true purposes, such as Avatar (colonialism), District 9 (apartheid), or the original Godzilla (nuclear horror). Rather, these are films whose symbolism either a) would not be apparent to the casual viewer, or b) would require a specific contextual understanding in order to fully appreciate their messages. At times, these obscured themes may seem to have little or even anything to do with the literal plot.

Why would some filmmakers choose to be so cryptic? As we will see, this method is usually employed when the message trying to be conveyed is something that one would be wise not to bring up more openly, often because it is a relatively unpopular viewpoint or concerns a sensitive subject. The desire to express subversive political and religious opinions, as well as to bring attention to certain ugly or shameful truths and/or shed light on uncomfortable or taboo subjects, are especially common reasons to cloak these topics in more conventional forms of storytelling.

Sometimes the message is so hidden that some may even doubt it is present at all. Therefore, this list will also refrain from looking at movies with fan-made conspiracy theories and focus instead on works whose hidden meanings have either been confirmed by their writers or directors, or whose clues are so numerous that the subtext is impossible to ignore once illuminated. Frequently, a simple fleeting but overt reference is all that is necessary to point us in the right direction, like a guiding signpost. Of course, it is indeed conceivable to sometimes go too far, reading too deeply and possibly misinterpreting irrelevant details. Film analysis is not an absolute science, so one must proceed cautiously. Still, when going about cinematic deconstruction carefully and competently, the results can be supremely satisfying.

15. The Brood (David Cronenberg, 1979)

The Plot: A psychotherapist (Oliver Reed) uses an innovative technique on one of his institutionalized patients (Samantha Eggar) that causes her to unconsciously create a “brood” of killer children – physical manifestations of her rage – while battling her husband (Art Hindle) for custody of their young daughter.

What It’s REALLY About: Divorce and child custody conflict

Wait, What? The meaning behind this seemingly innocuous little Canadian horror movie wouldn’t be that hard to see if one wasn’t distracted by all the violence and gruesome imagery. In truth, making the film was a cathartic experience for Cronenberg, who had been entangled in a bitter custody battle prior to writing the script. He has called the film autobiographical, even going as far as to partially model Eggar’s character on his now ex-wife. One can observe Cronenberg’s tendency to obliquely address important societal issues in subsequent films of his, be they the slow and horrifying progress of disease in The Fly (1986), or the nature of sexual fetishism in his notorious 1996 film, Crash.

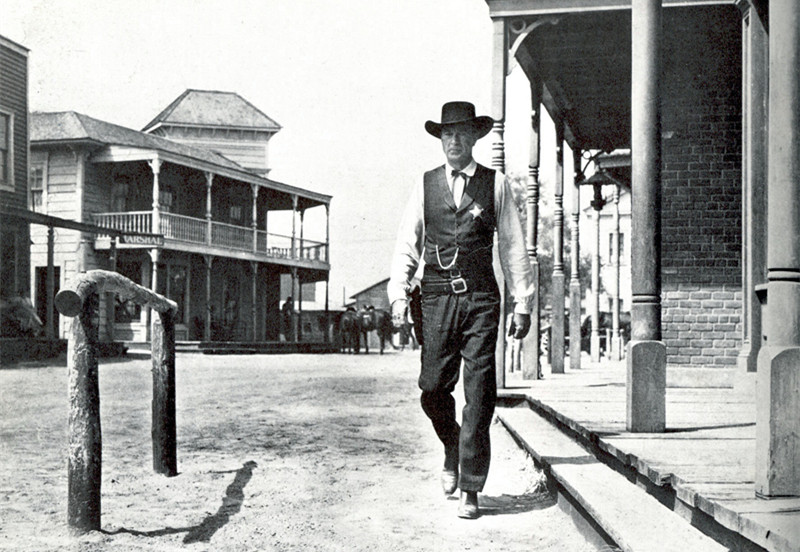

14. High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952)

The Plot: On the day of both his marriage to a pacifist Quaker (Grace Kelly) and supposed retirement, a town marshal (Gary Cooper) is given less than two hours to decide what to do about a gang of killers headed for his town – a conflict that, playing out more or less in real time, is complicated by his realization that none of his neighbors seem willing to help.

What It’s REALLY About: McCarthyism

Wait, What? To understand this one, one must take into account when the film was made. Shot in 1951 during the Korean War, the film’s plot is heavily influenced by events concerning the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Carl Foreman, the screenwriter, was called before HUAC as he was in the process of writing the script and refused to name names, causing him to be labeled an “uncooperative witness.” He was blacklisted shortly thereafter.

Watching the film with this background knowledge, it’s impossible to disregard the parallels between the town’s inaction in the face of incoming danger and the refusal of many in Hollywood to stand up for their persecuted peers. The film isn’t quite as blatant with this idea as other works about McCarthyism were at the time, such as the plays The Crucible (1953) and Inherit the Wind (1955), so it’s understandable how the message of this thoughtful Western could go over the heads of modern viewers unaware of the circumstances under which the film was made.

13. Prometheus (Ridley Scott, 2012)

The Plot: In this futuristic pseudo-prequel to Alien, a team of scientists and an android venture to an uncharted moon in search of the origins of human life.

What It’s REALLY About: Christianity

Wait, What? There’s more going on than meets the eye here, as is also the case in the other entries in this sci-fi horror franchise (but more on them later). Some have read the film as an exploration of the central tenets of Christianity, as first suggested in the opening scene in which one of the film’s humanoid Engineers sacrifices himself, his DNA being the catalyst for the creation of life. There are clues throughout the film that allude to Christianity, the most obvious examples being that the ship lands on Christmas Day, the structure resembling an alien crucifix that the team encounters in a room inside a derelict spaceship, and the unnatural “pregnancy” of the only cross-wearing member of the crew.

A much subtler reference is the name of the moon – LV-223 – which seems to refer to Leviticus 22:3, a passage that talks about the punishment prescribed for unclean descendants who approach sacred offerings. That the Engineers chose to destroy humanity 2,000 years ago is especially telling. Ridley Scott all but confirmed these suspicions when he stated outright that in an early version of the script, it is revealed that the Engineers had once sent one of their own to Earth… but we crucified him.

12. Who Framed Roger Rabbit (Robert Zemeckis, 1988)

The Plot: In a fantasy version of 1947 where humans and cartoon characters coexist, a detective (Bob Hoskins) prejudiced against “toons” must help exonerate Roger Rabbit when he’s accused of murder.

What It’s REALLY About: Racism and segregation

Wait, What? It’s not a stretch to say that the human-cartoon divide in this landmark achievement in visual effects closely mirrors the racial barriers that used to exist in the United States. Most of the film’s animated characters live separately in Toontown, though some have jobs in Hollywood as entertainers and are tolerated as such.

The Bob Hoskins character has disliked toons since one killed his brother years ago, though his bigotry is realistically portrayed as passive rather than virulent. The film’s 1940’s-era setting only enforces the metaphor, especially since none of the human actors are black, implying that the toons (a word only one letter removed from a certain racial slur, by the way) are a stand-in for them.

11. A Serbian Film (Srdjan Spasojevic, 2010)

The Plot: No atrocity or illegal paraphilia goes unexploited in this graphic shocker from Serbia about an aging porn star (Srdjan Todorovic) who is coaxed out of retirement by a lucrative offer to appear in one final film, only to later realize that the deal comes with a number of horrible catches (and that’s putting it mildly).

What It’s REALLY About: A criticism of the Serbian government

Wait, What? Viewers intrepid enough to brave this extreme horror film may be quick to dismiss it as simply an attempt by the filmmakers to test the limits of both good taste and censorship (it’s currently banned in many countries, including western ones). According to the film’s director, however, there’s actually a very deliberate message embedded in the depravity. “This is a diary of our own molestation by the Serbian government. We’re giving this back to you,” he has stated. He goes on to explain that the film is a parody of political correctness and a condemnation of typical state-financed Serbian cinema.

Its clearly high production values and relative lack of strong violence for its first half, not to mention its rather direct and self-reflexive title, make the director’s claims worth considering, though audiences unfamiliar with Serbian politics will be unlikely to interpret the film’s more extreme acts in the supposedly intended way. The most infamous scene, in which a newborn baby is raped, is said to be a literal representation of the idea that “in Serbia, you are fucked from birth.” Enough said.

10. The Brave Little Toaster (Jerry Rees, 1987)

The Plot: Five sentient household appliances set out on a journey to find their master after being left alone in a cabin in the woods.

What It’s REALLY About: Christian faith and/or the Holocaust

Wait, What? There’s no denying that this is one dark children’s movie. There are multiple references to suicide, vague sexual innuendoes, and a nightmare sequence featuring an evil clown. But it’s the underlying adult metaphors that really cut to the bone. One can read the film as a Christian allegory, as the appliances search for their master (God) after feeling abandoned, at one point singing a song titled “City of Light” whose lyrics clearly evoke heaven and salvation. There are also several scenes of self-sacrifice that lead to later repair (or resurrection, if you will).

Alternatively, the Holocaust appears to be on the film’s mind on more than one occasion, starting when the lamp, his bulb burnt out, startlingly laments, “That’s it! I’m burnt out! Eighty-sixed! To the showers!” Later, a blender is taken apart in a chilling scene basically presented as a vivisection, reminiscent of Nazi human experimentation, and the film’s climax takes place in a veritable death camp for singing cars (who are not rescued, but rather, mercilessly destroyed onscreen). That several of the filmmakers later came to work for Pixar, whose Toy Story 3 has been interpreted by some as a Holocaust allegory as well, lends support to this dark interpretation of the film.

9. Aliens (James Cameron, 1986)

The Plot: In this sequel to Ridley Scott’s sci-fi horror classic, Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) accompanies a team of Colonial Marines to investigate the now terraformed planet where she and her doomed crew first encountered the deadly creature.

What It’s REALLY About: The Vietnam War

Wait, What? Released eleven years after the war in Vietnam ended, Aliens is a movie dominated by a military presence. It would seem fitting that imagery hearkening back to Vietnam would be included, given the close temporal proximity between the film’s release and the conflict, but Cameron goes further than that. While the aircrafts, uniforms, and personalized gear on display all call Vietnam to mind, this could all potentially be subconscious.

Cameron, however, has gone on the record saying that the film is meant to evoke the Vietnam War thematically as well as aesthetically, as the soldiers find themselves outmatched by an enemy that, while less technologically advanced, proves more lethal than expected, especially as the marines are fighting on the aliens’ home turf. Even in the future, arrogance and overconfidence are shown to still be problems in the military that can have deadly consequences. In the immortal words of Bill Paxton’s Private Hudson, “Game over, man! Game over!”