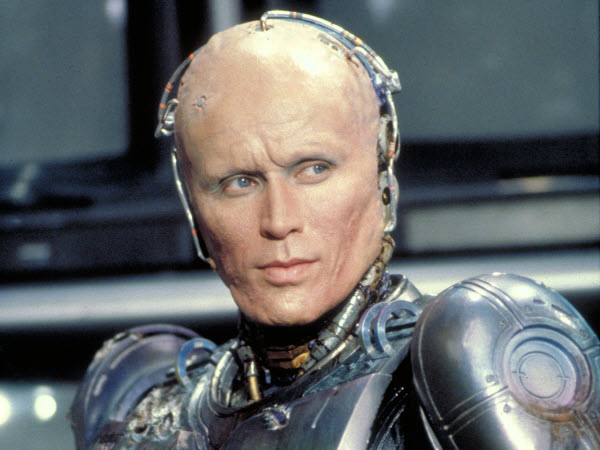

8. RoboCop (Paul Verhoeven, 1987)

The Plot: In a futuristic Detroit, Officer Alex Murphy (Peter Weller) is brutally gunned down by a gang of criminals, only to be brought back to life as a crime-fighting cyborg (justifying the film’s tagline: “Part man. Part machine. All cop. The future of law enforcement.”).

What It’s REALLY About: Jesus Christ (once again)

Wait, What? Director Paul Verhoeven has made no secret of his aim to portray the title character as a Christ figure. After all, Murphy suffers a cruel and painful death at the hands of laughing sadists, only to be resurrected and become a savior figure. The biggest visual clue comes at the end, when RoboCop walks through shallow water, appearing to almost walk on top of it. Of course, turning the other cheek isn’t exactly RoboCop’s style. As the Dutch director has stated, he’s “the American Jesus.”

7. Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979)

The Plot: Responding to a distress signal, the crew of a commercial towing spaceship unwittingly picks up a hostile parasitic organism that begins to grow in size and slaughter the crew one by one.

What It’s REALLY About: Rape

Wait, What? Though it may not seem obvious at first, everything about the eponymous extraterrestrial is calculated to conjure up unsettling images of sexual violation. From its phallic head and inner jaw to its “vagina dentata” mouth (lined with K-Y jelly to simulate the saliva), the H.R. Giger-designed creature is like a sexual nightmare made flesh. Its life cycle is no less disturbing: The creature orally rapes its victims, forcibly inseminating them before eventually bursting out of the host’s body in an orgasmic shower of blood and viscera. And naturally, the limbless chestburster form is also phallic.

All of these insidious associations were screenwriter Dan O’Bannon’s plan from the start, and it was he who suggested Scott hire Giger to create the famous monster. The sexual imagery of the alien is reinforced by its point of origin, illustrated through the derelict ship’s vagina-shaped openings and inner chamber containing eggs, whose design were originally so evocative of female genitalia that they had to be altered. Add a hidden android character that bleeds milky white fluid and you have a film awash in near-pornographic visual metaphors.

6. Eraserhead (David Lynch, 1977)

The Plot: A mild-mannered man with an usual hairstyle (Jack Nance) endures the urban decay around him and the incessant screams of his grotesque newborn baby while dreaming of a better place.

What It’s REALLY About: The fear of fatherhood

Wait, What? This surreal and Kafkaesque story is loaded with an array of rich symbolism, from giant sperm creatures to oozing cooked chickens to the unforgettable baby, which looks more animal than human. Little here is meant to be taken literally, as the story is about as far from a straightforward narrative as you can get. The puzzling elements of the film are hardly random, however, coming together to express overarching themes of alienation, helplessness, and nightmarish bewilderment at one’s surroundings.

The film’s most tangible message, however, is the frightening prospect of fatherhood, especially when it’s unplanned (the protagonist is bluntly informed of his baby’s existence by its grandmother). Lynch has made no secret of his unpleasant experience living in Philadelphia prior to making Eraserhead, which certainly informs the industrial landscape that serves as the film’s decrepit setting. Yet it is the difficult manner in which some men must come to terms with becoming fathers that is the main focus of horror in this bizarre and unquestionably unique art film.

5. Funny Games (Michael Haneke, 1997)

The Plot: Two innocent looking young men take a family of three hostage at the latter’s vacation home and proceed to physically and psychologically torture them for no apparent reason.

What It’s REALLY About: The impact of media violence

Wait, What? Director Michael Haneke stated in an interview that, “If the film became a big success, it would be because it was also misunderstood.” Clearly, this is not an ordinary film meant for mainstream viewers. Haneke apparently believed he hadn’t reached his intended audience, however, leading him to remake the film, shot-for-shot, ten years later with an English-speaking cast that included Tim Roth and Naomi Watts. Scenes where the two psychos break the fourth wall and even reference the fact that they’re in a movie reveal that there’s a lot more going on here than just a horrifying home invasion.

Haneke subverts our expectations from beginning to end, throwing in red herrings and (SPOILER ALERT) having the bad guys “win” by murdering the entire family – including both the dog AND the child – and go unpunished. Doing this runs the risk of irritating, frustrating, and even enraging the audience, though perhaps this is the point.

Truffaut once said that it was impossible to make a true anti-war movie because films tend to make war look exciting. In that vein, this is Haneke’s version of a horror movie minus the vicarious entertainment factor, as odd as that may sound. By attempting to portray violence in all of its grim ugliness, the film succeeds in that it is quite disturbing, but never glamorizes the bloodshed (most of it occurs offscreen and is not at all graphic). It is in this way that the message becomes clear: we, the audience, are guilty of enjoying fictional violence without appreciating its true horror. That’s never going to be an easy pill to swallow, nor a popular or necessarily enjoyable one.

4. The Wizard Of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939)

The Plot: A teenage girl from Kansas (Judy Garland) is whisked away to a whimsical world of color and magic, where she encounters witches and befriends three similarly lost characters on her quest to meet a wizard and return home.

What It’s REALLY About: Populism

Wait, What? It may seem unlikely that one of the most beloved movies ever made – a true example of cinematic escapism – could also hide a cynical political agenda. Yet the clues are all there, starting with the title (“Oz” is the abbreviation for “ounce,” a way by which gold is measured). Granted, the allegory was old even then, hearkening back to turn of the century events, but when you start to add things up, the intent becomes unmistakable. The Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion represent farmers, the steel industry, and Democratic politician William Jennings Bryan, respectively.

The Yellow Brick Road is the gold standard, and Dorothy’s slippers (ruby in the film but silver in the book) represent the alternative. And of course, the Emerald City and its fraudulent wizard symbolize the deceptive value of green paper money. This might all seem rather far-fetched, but the sheer multitude of allusions (there are plenty of others) leaves little doubt that this was more than simply a story about a homesick farm girl.

3. The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (Peter Greenaway, 1989)

The Plot: The wife (Helen Mirren) of a brutish oaf (Michael Gambon) begins an affair with a bookshop owner (Alan Howard) after her husband acquires a high-class restaurant formerly run by a French chef (Richard Bohringer).

What It’s REALLY About: An attack on Margaret Thatcher and her conservative government

Wait, What? One can easily be forgiven for failing to notice the pervasive symbolism in this one. To understand it, one must have a familiarity with both the target of the criticism (in this case, Thatcherism), and the intentions of the director, who explicitly stated that his film “started as a kind of diatribe against Thatcherite Britain.” Okay, so what exactly is going on here? In a nutshell, the “thief” of the title represents the greed and vulgar arrogance with which the director charges Thatcher, and the abused wife stands for the common Briton. Her secret lover is the intellectual but powerless opposition, and the cook is the obedient but resentful common civil servant.

How is one supposed to glean all this? Well, political symbolism isn’t the only metaphor hidden here – the different rooms of the restaurant, including the bathroom, are meant to symbolize the journey food takes as it enters and eventually leaves the body. The rather disgusting opening scene, in which the thief smears excrement all over the cook, establishes the extreme and unsubtle nature of the film, while also communicating to us that much of what literally happens will be but a visual symbol for something else.

Featuring a memorable score by Michael Nyman and effective performances all around, this is arthouse cinema at its most baroque and simultaneously blunt. Its audacity earned it the dreaded NC-17 rating, a move that likely only galvanized those who understood the anti-Thatcher message and feared for the film’s distribution and potential for being censored.

2. Drag Me To Hell (Sam Raimi, 2009)

The Plot: After being pressured by her boss to deny a mortgage payment extension to an old gypsy woman (Lorna Raver), a young loan officer (Alison Lohman) finds herself on the receiving end of a vengeful curse that subjects her to three days of gruesome hallucinations and paranormal attacks that threaten to culminate in a one-way ticket to Hell.

What It’s REALLY About: Eating disorders (bulimia, specifically)

Wait, What? Leave it to the guy who created the Evil Dead franchise to turn an otherwise run of the mill horror movie (one of the best ever made that works within the boundaries of a PG-13 rating) into a meditation on one of life’s most uncomfortable and taboo horrors. To start, if the film were a psychoanalysis patient, it would no doubt be characterized as exhibiting an oral fixation. Throughout the film, Christine, the tormented protagonist, has various objects forced in and out of her mouth and throat, from vomit to insects to embalming fluid to a possessed scarf.

Fair enough – that’s just one viscerally consistent way to disturb the audience, right? True, but take into account the following details we learn: Christine used to be fat and owned a prize-winning pig at the 1995 “Pork Queen Fair,” addiction runs in her family (her mother is an alcoholic), she lies about being lactose intolerant, the supernatural attacks throughout the film seem to revolve around food or occur when food is present, and the gypsy woman who places the curse on her suffers from damaged hair, fingernails, skin, and teeth – all of which are symptomatic of bulimia (a word that sounds awful close to the name of the demon tormenting Christine, the “Lamia”). At some point, one must admit that this can’t all be mere coincidence, and the result is as frightening as it was intended.

1. The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980)

The Plot: Struggling writer Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) bring his wife (Shelley Duvall) and young son to the Overlook Hotel for the winter to serve as off-season caretakers, but the hotel’s isolation and violent history begin to take their toll on Jack’s mind, which his psychic son begins to sense.

What It’s REALLY About: The annihilation of the Native Americans

Wait, What? Much has been made over the years about the possible hidden meanings present in The Shining, from charges that it’s secretly about the allegedly faked moon landings to its subtle (and again, alleged) use of Nazi symbolism. Just recently, a rather bizarre documentary called Room 237 was made centering solely on these concepts and more. Not all of the theories are nonsensical though, and the one that has perhaps the largest amount of supporting evidence is that the movie is really about what white settlers did to the original inhabitants of the United States.

The first clue is the hotel manager’s casual mention that the Overlook was built on an Indian burial ground – a detail not present in the novel. Such changes are especially noteworthy, given Kubrick’s reputation for meticulousness and perfectionism. The hotel is filled with Native American motifs and artwork, one of which Jack repeatedly throws a tennis ball at, but no Native Americans are ever seen. Jack’s seemingly random use of the phrase “white man’s burden” at the bar and the red, white, and blue wardrobe he wears toward the end of the film are certainly telling, as is the fact that the past ball that is referenced throughout the film took place on July 4th (hardly a celebratory day for Native Americans).

Even the marketing of the film is suggestive of this theory, as demonstrated by the tagline on the film’s European posters, “The tide of terror that swept America IS HERE.” The deluge of blood that gushes forth from the elevator can be seen as representing that of the slaughtered Native Americans, as the tract of land the hotel occupies can stand in for the whole country – a nationwide burial ground. Even the name of the hotel, the “Overlook,” seems to mockingly refer to our indifference to the genocide that paved the way for the country as we know it today.

Whether or not Stephen King intended all this in his novel is questionable (he saw it more as an exploration of the evils of alcoholism, which, though present in the film, is hardly the central focus). Kubrick’s translation of the source material, however, leaves little doubt that the horrendous consequences “Manifest Destiny” had for the Native Americans were not all that far from his mind when making this seminal horror masterpiece. But why not be more explicit about this serious point? The inability or unwillingness of the average viewer to see it proves exactly what Kubrick may have been trying to say, making this the ultimate meta example of how one can skillfully weave a hidden and unsettling meaning into one’s film with artful and clever subtlety.

Author Bio: Jason Turer received his B.A. from Cornell University with a double major in Film and English, and currently works in television production in Brooklyn. He has too many favorite films to list here, but some of his favorite directors include Kubrick, Cronenberg, Hitchcock, and Lynch.