14. Yentl (Dir. Barbra Streisand, 1983)

Yentl (Streisand) is an independent Polish woman whose father, unbeknownst to their neighbors and friends, teaches his daughter about the Talmud. When her father dies, Yentl moves to a different town, disguises herself as a man named Anshel, and continues her studies at a religious school.

To the uninformed, Yentl is just that film in which Babs sings to her dead father. To those who have seen the film, it is a brilliant depiction of a woman challenging patriarchal notions relating to a woman’s place in society and religion. Beyond its campy appeal, Yentl uses musical conventions, such as song interludes, to depict Yentl’s emotional state/sexual exploration.

Yentl’s ultimate reveal of her gender is another slap in the face of patriarchal society, providing her with an ultimatum: live as a repressed housewife with the man of her dreams, or hold onto her independence. Yentl chooses her independence, moving to America in order to enjoy more opportunities than her repressed Polish town can offer.

13. Daughters of the Dust (Dir. Julie Dash, 1991)

Julie Dash endured a long struggle to make Daughters of the Dust, a nuanced portrait of three generations of Gullah women who reunite before moving north. Set in 1902, the unconventional narrative focuses on exploring the variety of women who each add their own voices to the ever-evolving story.

More than a film about race or gender, it is a film that challenges the notion of what stories can be told, how they can be told, and who is telling them. Dash’s long struggle is a shining example of how hard it is, but how fruitful it can be, to highlight these brilliant feminine perspectives.

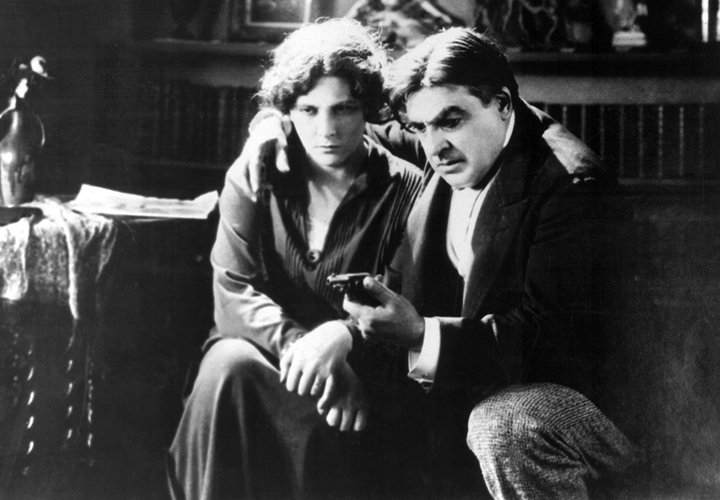

12. La souriante Madame Beudet (Dir. Germaine Dulac, 1922)

Germaine Dulac’s short follows the titular Madame Beudet who is trapped in a loveless marriage to a practical joker. During the day, Madame Beudet dreams of a better life for herself, and even imagines her husband’s ultimate death.

Many scholars consider La souriante Madame Beudet (The Smiling Madame Beudet) to be one of the first feminist films, primarily because of its exploration of female desire. It is an experiment of cinematic form and content, examining Madame Beudet’s daydreams through a series of superimpositions and slow motion sequences. It allows the viewer to explore a female perspective, one that is both emotional and transgressive.

11. Orlando (Dir. Sally Potter, 1992)

A chauvinist nobleman named Orlando (Tilda Swinton) inherits a large estate from Queen Elizabeth, who makes Orlando promise to never age. The plot takes a strange turn when, after nearly dying in a fight, Orlando discovers that he has fully transformed into a woman. From the 16th Century to the 1990s, Orlando endures the hardships of being a woman, including becoming a single mother and trying to publish a novel.

Based on Virginia Woolf’s novel of the same name, Potter’s provocative film examines the hardships that come along with being a woman. Though the film did not cater to everyone’s tastes, it created an interesting dialogue about dealing with the societal/patriarchal prejudices that come with gender.

10. Viskningar och rop (Dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1972)

Two sisters, Karin (Ingrid Thulin) and Maria (Liv Ullmann) reunite with their sister, Agnes (Harriet Andersson), who is dying of cancer. Bergman focuses his energy less on constructing a traditional narrative trajectory, and more on exploring themes of mortality, sexuality, and class through a feminine lens.

There is no denying the genius of Bergman, who not only knew how to craft brilliant characters, but also knew how to visualize their psychological states. Some of the most enduring images from Viskningar och rop (Cries and Whispers) come from the maternal Anna (Kari Sylwan), who lays Agnes on her bare breast, and from Karin, who masturbates with a broken piece of glass.

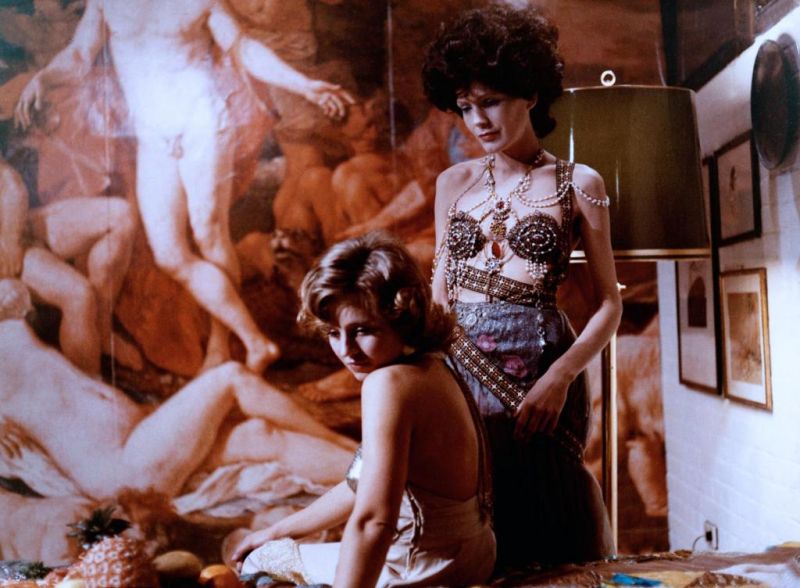

9. Die bitteren Tranen der Petra von Kant (Dir. Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1972)

Die bitteren Tranen der Petra von Kant (The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant) follows Petra (Margit Carstensen), a prominent fashion designer who juggles a series of sado-masochistic relationships with her model (Hanna Schygulla), her assistant (Irm Hermann), and her mother (Gisela Fackeldey).

Aided by Fassbinder’s keen eye for theatrical mise-en-scene, The Bitter Tears is an exemplary look at Fassbinder’s ability to create a complex variety of women (from meek and timid to sultry and villainous). Their relationships are defined by a sense of agency, with each woman deciding how she wants to be treated and how she wants to treat others.

The crème de la crème comes at the end when a remorseful Petra apologizes to her assistant, Marlene, only to have Marlene shun her in disgust (revealing that Marlene preferred being the submissive party in their work related relationship).

8. Persona (Dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

Alma (Bibi Andersson) is placed in charge of Elisabet (Liv Ullmann), an actress who had a nervous breakdown during the production of Electra. Rendered mute, Elisabet observes Alma, who manages to spill her secrets and disclose her fears to this silent witness. It is a film about identity and it is a film about form, constantly calling attention to the artificial nature of the medium.

Bergman has crafted many psychological and emotional portraits of women, but the duality of the two leads of Persona adds a complex feminine mystique into the mix (who can forget the image of Elisabet pulling Alma’s hair away from her face). He creates a complex film founded upon the psychological states of two emotionally unstable women, calling into questions the nature of existence, the artificiality of identity, and the fear of a silence.