7. Summer In Narita (Shinsuke Ogawa, 1968)

Not all of the new wave films were dramas and narrative pictures, there were a few documentaries associated with the movement as well. Shinsuke Ogawa’s 1968 film “Summer in Narita” is one of the most notable documentaries that emerged out of the Nuberu Bagu and was part of a series called the “Sanrizuka”, which would go on to achieve major historical significance.

The film is about the problems caused by the New Tokyo International Airport Corporation and the Japanese government, forcefully developing construction in rural areas of Narita. The construction plans were implemented without the permission of the local farmers and was so unpopular the government resorted to using riot police to keep order.

Unlike most documentaries of the time, Ogawa Shinsuke and his film crew actively participated in the confrontations, resulting in the film being both politically and emotionally fuelled. The high levels of passion and subjectivity, gives the film the same rebellious energy you find in the narrative new wave films.

6. Death By Hanging (Nagisa Oshima, 1968)

As a result of the film refusing to conform to traditional narrative conventions, “Death by hanging” is difficult to sum up into an abridged synopsis. In a nutshell, it observes a Korean convict who survives an execution by hanging and the problems his executioners are faced with whilst dealing with the dilemma. The effects of the failed hanging result in the offender suffering from amnesia. This causes major complications amongst the execution team due to the law stating that a person unaware of a crime cannot be executed.

It is known by fans of the director (Oshima) for its Brechtian-like methods, specifically its use of ‘epic theatre’ and ‘theatre of the absurd’ conventions. Oshima makes it clear to the audience that they are constantly watching a film, even to the extent of opening it in the format of an informational documentary. The film also addresses the prejudice attitudes towards Korean people in Japan at the time.

5. Funeral Parade Of Roses (Toshio Matsumoto, 1969)

Taking into consideration the time of its release, “Funeral Parade of Roses” was one of the most daring films produced within the new wave time frame. Dealing with both the underground gay culture of Tokyo in the 1960’s and a young protagonist that is a transvestite, it makes the themes in many of the other new wave films seem quite conservative.

The film centres on a young transvestite called Eddy, he is a popular figure amongst the gay community and pursues a relationship with a bar manager from the city’s shady gay scene. It is considered to be a gay adaptation of the ancient Greek myth of Oedipus Rex; with its correlating themes of self-inflicted tragedy, destiny and free will.

“Funeral Parade of Roses” masterfully merges sex, drug use and violence into a beautifully fragmented narrative.

Similar to Ingmar Bergman’s “The Passion of Anna” that was released the same year, metatextual techniques are used to add a postmodern slant to the movie. Interviews with the cast are incorporated into it; this gives the audience a more detailed insight, yet distances us from the film’s world at the same time. The film allegedly had a huge influence on Stanley Kubrick when he was making “A Clockwork Orange” in 1971.

4. Mandara (Akio Jissoji, 1971)

There is some speculation surrounding director Akio Jissoji’s legitimate association with the Japanese new wave, but personally I feel his work perfectly represents the tail end of the movement.

The film is about two young alienated couples from Kyoto that visit a hotel overlooking a beach. They become entangled in a religious cult led by a charismatic cult leader who violently advocates the elimination of social and sexual conventions. The cult itself is as much bizarre as it is unique, where potential female candidates are raped, and their partners are made to watch as a method of recruitment.

Like most Jissoji’s films there are some visual, specifically compositional correlations with the work of Yoshishige Yoshida. The stunningly unconventional cinematography perfectly utilises open space and composes its characters in such a way, they become immersed within the frame. The characters are visually at one with their environments, showing the influencing parallels between their subjective state of mind and that of their surroundings.

3. Bad Boys (Susumu Hani, 1961)

I’m quite certain adding “Bad Boys” to this list will be unpopular, but unlike Susumu Hani’s more well-known masterpiece “Nanami, The Inferno of First Love” its historical and thematic motifs are much more suited. There are also many critics and Japanese film historians that credit “Bad Boys” as the film that launched the “true” Japanese new wave, suggesting that all previous efforts were simply a build-up.

The film relies heavily on improvisation for both its overall narrative and non-professional performances. It follows the journey of a juvenile delinquent as he goes through a correctional program in a young offender’s reformatory. The protagonist meets other people (played by real young convicts) who are also confined, and they share their troubled stories with him.

Susumu Hani’s documentary background and experience using young people as subject matters, dictated both the narrative and the aesthetics of the film. A lot of the none-professional actors in “Bad Boys” were subjects in Hani’s previous documentaries and this certainly comes across in the authentic naturalism of the performances. It’s both moving, educational and even more importantly, a beautiful work of art.

2. The Naked Island (Kaneto Shindo, 1960)

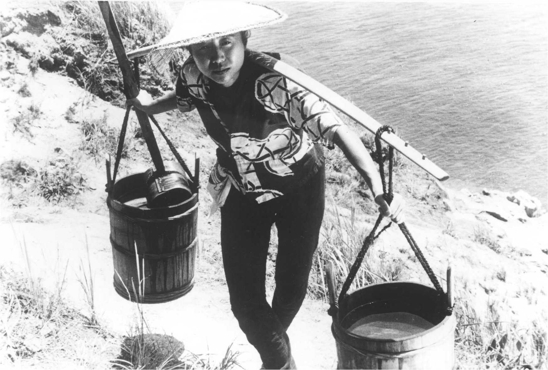

You have to give any movie credit that portrays a whole feature film narrative with almost no dialogue whatsoever. Visual storytelling is difficult, but depicting complex character development with only one line of dialogue is even harder, and Keneto Shindo’s “The Naked Island” pulls it off with flying colors.

The film is set over the course of a year on a small island in the Seto Inland Sea. Inhabiting the island is a family of four; a husband, wife and two sons. Being the only occupants on the island they survive solely by farming. Their daily repetitions are illustrated with the same poetic majesty as the rituals performed by Zen Buddhist monks. The family’s simple lifestyle exemplifies an aesthetically harmonious quality, which is presented beautifully through the films spacious cinematography, rhythmic editing and deceptively simple sound design.

All of this lyrical banality concludes with a heart-breaking finale, made more devastating due to the contemplative and detail-sensitive frame of mind the film had conditioned us into.

1. Eros Plus Massacre (Yoshishige Yoshida, 1969)

Arguably one of the most beautifully shot films in any era of cinema and directed by Yoshishige Yoshida (also known as Kijū Yoshida) who was one of the more poetically minded new wave directors. The film is an intertextual biography of a real life Japanese anarchist called Sakae Osugi and the events surrounding his notorious murder. Osugi’s story is paralleled with a separate narrative that follows two students who are researching into his political and ideological theories.

Yoshida allows the past and present worlds to merge, resulting in conversations and interviews between the characters in Osugi’s story and the student’s. “Eros” pensively analyses the relative nature of memory, reality and fabrication, forming an intricate contrast that insistently requires the audience’s participation. Not only does it challenge ideas surrounding revolution, but the often erroneous expectations of truth we frequently expect from the cinema.

With Yoshida’s trademark spacious compositions that resemble the minimalist framing used in classic Zen painting, it’s easy to be captivated by the visuals alone. The cinematographer for “Eros” was Motokichi Hasegawa, the former still photographer and title designer for three previous Yoshida films.

Author Bio: Matthew E Carter is a British world cinema blogger and part of a filmmaking collective called Black Country Cinema. His work usually focuses on documentary and East Asian cinema; primarily Taiwanese, Japanese, Chinese and Cantonese.