7. Autumn Sonata

“Chopin was emotional, but not mawkish. Feeling is very far from sentimentality, The prelude tells of pain, not reverie. It hurts, but he doesn’t show it.” – Charlotte Andergast (Ingrid Bergman)

Which is also apt in describing Eva (Ullman) living an emotionally conflicted life haunted by distrust and devoid of the affection she yearned for but never received. Just as any Bergman dialogue, Autumn Sonata is layered in symbolic metaphor, straightforward angst, despair, and unflinching emotional brutality.

The film is nothing short of a heart stopping chamber drama, luring the audience in to seize them by the throat and suffocate them in this mother and daughter warfare. Most of all and given the claustrophobic setting, this film gives chance for Bergman to film two of the greatest actresses full power to unleash all of the pent up raw tenacity that they possess.

It’s a performance film above all and Nykvist photography and Bergman’s dialogue just elevates the quality and stature of the movie. This film is indeed Ingrid’s swan song to cinema as it would be her last theatrical released film (she finished with a television made film) but she was already with knowledge of her fatal cancer at the time and her pain and anxiety is ever so present in her role here.

6. The Virgin Spring

Bergman weaves a medieval tapestry of murder and revenge, a story as simple and age old as the biblical morality tale of begotten violence with Cain landing that fatal blow to his brother Abel. Ingmar uses specific devices to make the plot not seem as cut and dry (simple) with the violence not black and white in determination of its virtue.

The film contained a raw power and emotional impact that is more heightened than in most of Bergman’s films perhaps due to its universal theme of death and revenge. Bergman implants devices in attempt to make the film more complex hence its themes on violence and even religion at times contradictory but all the more thought provoking.

The innocent boy in the trio of Herders is surely a stand in example to prove nothing is 100% evil just as the Töre’s vengeance proves nothing is 100% good in the world. The one thing that is for certain is the emotion we as humans experience in the face of such atrocities. Bergman summons that feeling out of the viewers with this film, challenging them all along the way.

5. Wild Strawberries

This is in fact the most warm and nostalgic of all Bergman’s films and it is essentially his “road movie”. Wild Strawberries takes the viewer on a journey through dreams and time.

Bergman has the rare opportunity that does not happen very often to be able to direct his idol in a film Victor Sjöström; the man who influenced him to be a filmmaker. Despite their deep mutual respect for one another, the production to this film was a rough and rocky patch between the two men and the master/mentor reversal.

Still we are glad these two cinematic giants could cross paths to make such a classic film. And whatever hardships faced between the two men was not in vein as Sjöström’s portrayal as Dr. Isak Borg was meditatively jarring as an elderly man reevaluating his life and reminiscing on his past.

Thus the universal theme of growing old and living with regrets while still cherishing the warm memories that we forever cling to. Bergman hits the old age thematics hard with his now famous dream sequence in the beginning of the film. The symbols of the handless clock representative of no time or that his time is up. The bloated face man who disintegrates on the street could be interpretative of the fragile existence of the human body. And the most important symbol of all being the deceased doppelganger foreshadowing one’s own impending death.

This morbid incantation of the mind is what sets Dr. Borg on an impulsive journey into his own past for self-discovery and reconciliation to move forward with his future. Wild Strawberries is a rare cinematic treat from Bergman that differs from his usual moniker as the Swedish miserablist. It’s oddly optimistic and nearly a family tale of growth and understanding of one another.

4. The Silence

Differing from Bergman’s usual tropes is the fact that The Silence takes its title seriously and it contains the least amount of dialogue than in any other Bergman film (at least that I have seen). This of course is part of the film’s magic giving way for visual storytelling in replace for his usual monologues and malicious diatribe between characters. That of course is still present but holds out until the film nears its climax.

The movie is also unlike many Bergman films previous to it because the manner in which the film was shot. Only here and then later in Fanny and Alexander did Bergman experiment by shooting his film through the point of view of a child. Sven Nykvist makes the most of this by filming the baroque hotel akin to a labyrinth of playful possibilities in the imagination of the boy. His fluid movements with the camera following the boy around every corner, at times hanging from the ceiling capturing these magnificent downward POV shots were an absolute marvel.

Unofficially apart of the so called faith based trilogy (loss of faith) with Through a Glass Darkly and Winter’s Light, the connection between the three is almost too loose to be considered a trio. The God element in this film is easy to spot because it is not there, God is absent from this world and God is silent. So instead and more importantly, do we see bleak thematics come into play.

The innocence of a child slowly becoming corroded by susceptible and exposing light to hedonistic lifestyles from his mother, dying regret and remorse from his aunt, and virtual abandonment by the ones he loves being sent off like a pawn. The Silence is a strange hybrid of a Bergman film.

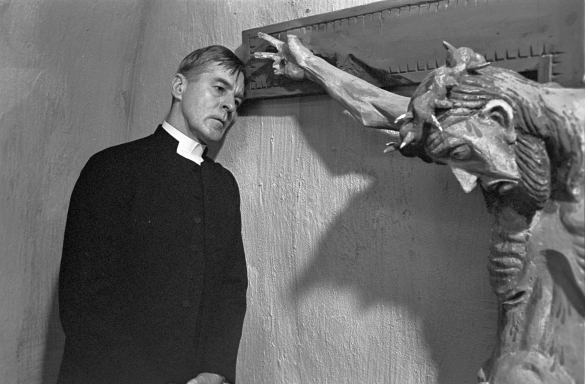

3. The Seventh Seal

Danse Macabre and the philosophical questions of life at the verge of death. The Seventh Seal is the film that put Bergman on the map as a force to be reckoned with in the world of cinema. Despite gaining much praise from his previous film Smiles of a Summer Night from the year before, it was this film which won the Special Jury Prize at Cannes that set him on the path to iconic status among film critics.

What makes The Seventh Seal on top of the elite is how Bergman works with such smaller scale production values, few locations and his brilliant ideas and philosophy to make an apocalyptic film of epic proportions. This film feels like it is on a grand scale yet it only contains a few characters and set pieces throughout. This is evidence of Bergman’s genius at hand and how his writing can easily provide thought provoking material while his directorial prowess can transform a film of little means.

The plot of the film is haunted by the recent Crusades yet they are never shown in the film, no large battles or brutal violence yet Bergman so easily manipulates the viewer that we believe with the utmost certainty we entered our story on the traces left behind of this horrid historical war. He does the same with the rumors of evil omens and apocalyptic forth comings that we again believe at any moment fire may reign down from the Heavens onto our cast of characters in their god forsaken land. The plague is another element never really shown and only talked about yet its deathly presence surrounds the film.

These elements do not scream of a film set in a small area but yet it is and still it makes the story appear to be effected from worldwide perspective. The Seventh Seal may not be Bergman’s best film but it contains all of the qualities that make up what we now consider today to be essential Bergman.

It has aesthetic photography of the highest order, unnerving sound and atmosphere, and intellectual thought played out through theatrics of its characters in angst. The movie is a lesser masterpiece in Bergman’s expansive filmography but a masterpiece no less.

2. Winter Light

Winter Light is an example of a perfect film at least in the Bergman vocabulary sense. For a film designed almost in a theatrical concept for its minimalism, it remains largely cinematic and achieves a great deal over the course of an hour in real time and only an afternoon in film time.

In the space between morning congregation and afternoon ceremonies, the lives of a small group of individuals are tested in the most brutally realistic and subtle of ways. Bergman examines their relationships as often is his expertise at dissecting the human condition, and does so here in flawless form and tremendous ease.

Remember it’s only an afternoon spent with this handful of characters and yet with an emotionally revealing letter, a failed attempt at guidance and a heart breaking revelation exposed; we have the ability to not only relate but engross ourselves as the audience into their anguish and empathize with their conflict.

In this frostbitten and desolate world of Winter Light there is not much love or warmth to be found and if God is love as Bergman reiterates after stating the same in Through a Glass Darkly then God is completely absent here.

1. Persona

Hyperboles do not matter when discussing Persona because the film is all but stated in fact that it is not only Bergman’s masterpiece but holding the incredible feat of being considered one of if not the best film ever made. There are many factors that go into Persona carrying this title perhaps even too many to explain, but needless to say it has every element that a perfect film should have.

From the famous opening sequence that is an editor’s paradise (in fact often cited as an example of the best edits in film history) to Nykvist’s iconic shots and frames with light and texture; the way he molds the two actresses with the camera utilizing shadow and pose to his advantage. All under the masterful direction of the cinematic giant himself pulling the strings as head puppet master delivering a complex tale that is both coherent and incoherent simultaneously.

The film has a double edged sword of surrealism and realism that forever keeps the audience at bay but also imprisons them to be engaged with the material. It is the epitome of an interpretative film that offers vast richness in film discussions. Persona is a film where it is easy for the words to flow when speaking of it. It’s the kind of film that entire books could be written on. Most of all though it is a timeless classic of world cinema that will never be forgotten in the medium of film.

Author Bio: Robert Beksinski III is a Baltimore, MD native but currently residing in Chambersburg, PA. Just like any other cinephile; film has become an integral part of his life and the drive to fuel his cinema addiction has also drove his needs to write about films. Which brings us here. You can find him at Letterboxd here: http://letterboxd.com/bbeksinski/.