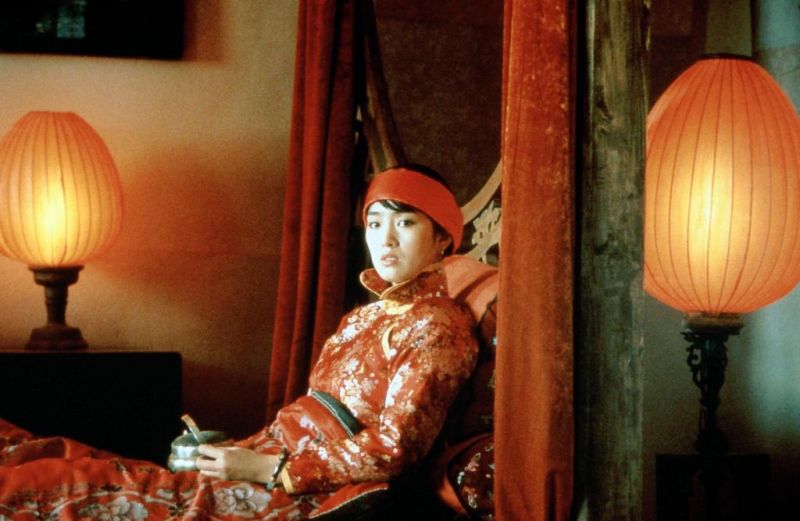

15. Raise The Red Lantern (1991) – Mainland China

Set in 1920s China the film is an adaption of the novel “Wives and Concubines” by Su Tong and is about a nineteen year old woman who becomes one of the concubines of a wealthy Lord. The film shows the competitive nature between the concubines and the repercussions of psychologically slave like conditions.

It could so easily be regarded as one of the most beautiful films ever made. It also proves that when director Zhang Yimou isn’t trying to give us cinematic diabetes with his over bearing sentimentality or gimmicky plot twists, he actually produces great films.

Yimou can be a master at embracing the beauty of a place and penetrating the poetic value in human suffering. “Raise the red lantern” is arguably his best example of this gift and beautifully embraces the environment of a film, which is essentially set in one location.

The film stars a young Gong Li who pulls off a phenomenal emotionally reserved performance and proves yet again the best actors are the ones who master subtlety.

14. Center Stage (1993) – Hong Kong

“Center Stage” is a metafiction film about the complicated life of Chinese silent film star Ruan Lingyu. If you are not familiar with the term metafiction, it signifies a film that self-references and often makes the audience aware that it knows it is a film.

The narrative of the film parallels with footage of the director Stanley Kwan and other cast members discussing Ruan’s life. By showing this documentary like investigation, Kwan has set up an honest foundation for the film. Even if he gets certain facts wrong at least he can show that he was sincere and that’s really the closest any filmmaker can get to truth.

The film needed this personal element from Stanley Kwan; it is as much about Kwan’s personal journey as it is Ruan’s. Along with the likes of Wong Kar-wai, Fruit Chan, Clara Law, Peter Chan and Evans Chan, Stanley Kwan is one of the most notable directors of the Hong Kong Second Wave movement.

13. The Peach Blossom Land (1992) – Taiwan

“The Peach Blossom Land” is a post-modern masterpiece and one of the most significant works of the Second wave of Taiwanese cinema. Originally a smash hit play; it concerns two theatre crews who are hoping to do one final run through of their plays. But a problem occurs when the theatre has double booked them in and as a result, they have to take it in turns rehearsing.

One play is a drama (“Secret Love”) set just after WWII where two lovers who no longer can be together have to migrate to Taiwan from China. The man gets old but can never free himself from the memories of the young woman he once loved. The second play is a comedy based on an old Chinese poem called “The Peach Blossom Spring”, where a fisherman stumbles upon a beautiful land where everything is covered with peach blossoms.

The film is about time, place, memory and nostalgia, done in one of the most creative ways cinema can offer.

12. Still Life (2006) – Mainland China

“Still Life” is often cited as the archetypical sixth generation Chinese film and epitomized the aesthetic style of its director Jia Zhangke. Filmed in a small village in China called Fengjie, which is located on the Yangtze River (longest river in Asia). The town is in the process of being demolished to make room for the massive Three Gorges Dam project.

The film tells the story of two people visiting Fengjie in a desperate pursuit to find their missing spouses. “Still Life” addresses the profound emotions people invest into their environments; this is a theme common in both Jia’s and other sixth generation films. Eventually we all become part of our own landscapes and when they are made to change, so are we. The idiosyncratic cinematography and perfectly captured transcendent moments make the film impossible not to appreciate.

11. Oxhide (2005) – Mainland China

Understandably many critics refer to “Oxhide” as possibly the most important film of contemporary Chinese cinema. The film portrays the director’s family (Liu Jiayin, who was only 23 when she filmed it) and their crammed apartment in Beijing.

“Oxhide” is as if Robert Bresson shot a film written by Yasujiro Ozu or Shimizu Hiroshi. Its narrative emphasises the importance of the small nuances within a family household, but is shot with a sense of minimalism and distance. The cinematography generally focuses on the environment (domestic appliances etc.) and the sound on the people. This creates a visual-audio contrast between characters and place, signifying the effect the surroundings have on the family and vice versa.

Its unusual use of a wide 1:2.35 aspect ratio magnifies the small details of the apartment, helping us appreciate the understated importance of the deceptively mundane.

10. Ah Ying (1983) – Hong Kong

Before Fruit Chan naturalistically depicted the everyday lives of the people of Hong Kong, there was New Wave master Allen Fong.

Fong’s celebrated docudrama “Ah Ying” was sadly one of very few films he produced in his short career. It chronicles the life of a young woman as she attempts to become part of Hong Kong’s independent film scene. It is an incredibly well observed piece, which may have something to do with it being based on the actual actress’s (Ah Ying) real-life experiences. It portrays the cultural nuances of the lives of poor young people in Hong Kong during the 1980s and almost critiques the declining integrity within Hong Kong cinema.

At a time in Chinese cinema where heroines were expected to be immaculately and unrealistically beautiful, Ah Ying says to her love interest “I have so many pimples”. He responds “yes you do have pimples, but I don’t care”. For a Cantonese film at that time to use a female protagonist who was not conventionally or commercially beautiful was very rare indeed.

9. The Arch (1969) – Hong Kong

Many Chinese film historians consider Tang Shu Shuen’s “The Arch” as the film that launched the Hong Kong New Wave. It is a carefully crafted story about a woman trying to deal with the callous etiquettes of society, whilst instantaneously seeing her personal happiness pass her by. The film forces us to ask the question “Is a legacy or reputation within life, more important than fully experiencing the life itself?”

“The Arch” is a period melodrama staring Lisa Lu as a widow who suppresses her requited desire for a virile young general, in favour of feudal virtue and an Arch to be raised in honour of her. At the time Arches were constructed for people of high social regard, if Lu’s character was to pursue the gentleman she would risk damaging her reputation and losing her potential esteem.

The film is beautifully shot (partly) by Satyajit Ray’s frequent cinematographer Subrata Mitra and typical of Tang Shu Shuen’s experimental influences, powerfully utilises freeze frames.

Despite the film presently being recognised as a ground-breaking Hong Kong production, it was actually funded and edited by American affiliates. This is a testimony to how timid Hong Kong studios were about supporting experimental productions at the time.

8. Vive L’Amour (1994) – Taiwan

A perfectly paced film about metropolitan alienation in Taipei, it observes three strangers who share an apartment together unknowingly. The Influential and critically celebrated director Tsai Ming-Liang became the face of Taiwan’s ‘Second Wave’, and brought it to the attention of international audiences when his film “Vive L’Amour” won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1994.

In spite of the plot being what many would consider ‘improbable’, it never relies on gimmicks or coincidences to make it work (and yes, it does work). With hardly any dialogue or accessible narrative conventions, Tsai expertly and invisibly unravels his characters to their very core. The film ends on what seems at first to be a drawn out sequence, but when it finishes it will almost certainly linger deep inside you for years to come.