7. A Touch Of Zen (1971) – Taiwan

Released in 1971 “A Touch of Zen” is a wuxia film directed by the legendary Taiwanese filmmaker King Hu. The film centres on an artist who lives with his elderly mother near an abandoned fort that is rumoured to be haunted by ghosts.

The artist meets a beautiful woman who moves into the eerie premises, later we discover she is being chased by mediators of an Imperial leader, the same troupe that slaughtered her family. The artist gets caught up in her predicament and is plunged into an epic adventure that consists of arguably the most beautiful battle scenes of all time.

In retrospect “A Touch on Zen” was the bedrock for contemporary Asian martial arts cinema. Films like Ang Lee’s “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” are indebted to its themes and technical aesthetics. The film was such a milestone it was the first Chinese language movie to win an award at the Cannes Film Festival.

6. Yellow Earth (1984) – Mainland China

“Yellow Earth” is about a Chinese soldier from the south who in the late 1930’s had been instructed to collect peasants’ old folk songs in order to re-write them with revolutionist lyrics. This was done in order to boost the spirits of the other revolutionary soldiers.

The film helped kick start the fifth-generation of Chinese cinema and was one of the few films of the time to rely primarily on visual storytelling. With a young Zhang Yimou conducting the cinematography, the film is a lyrically cryptic and breath-taking poetic depiction of a complicated period in China’s History.

The film occasionally uses musical-like conventions, allowing its characters to express their personal emotions with folk songs. Songs are usually used in musicals to represent a sense of intimate subjectivity with the characters, but ‘Yellow Earth’ still manages to form an objective perception of them. It challenges certain stereotypes that existed at the time, specifically the ‘uncivilized north’ and ‘pre-Mao progressive south’, as the film progresses you eventually realise that this is a stinker of a false dichotomy.

5. A Brighter Summer Day (1991) – Taiwan

When a group of young Taiwanese filmmakers broke away from the Kung Fu and melodramatic conventions of their national cinema, one in particular led the way, that director was the late Edward Yang.

Throughout the 1980s; Yang, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Yi Chang, Wu Nien-Jen, Chen Kunhou and many others aimed to depict the rapidly changing social climate of Taiwanese culture. Although each filmmaker had their own distinctive style their films all displayed restrained/naturalistic characteristics, to which many scholars have compared to Italian Neorealism and the Japanese Shomin-Geki genre.

It’s difficult not to consider “A Brighter Summer Day” to be the best film Edward Yang produced and could been seen as a summary of the new wave. With a surprisingly seamless 4 hour duration, the film is based partly on experiences from Yang’s own adolescence. The story is deceptively simple and focuses on a generation of young people challenging the restrictions of Taiwan’s cultural identity in the 1960s.

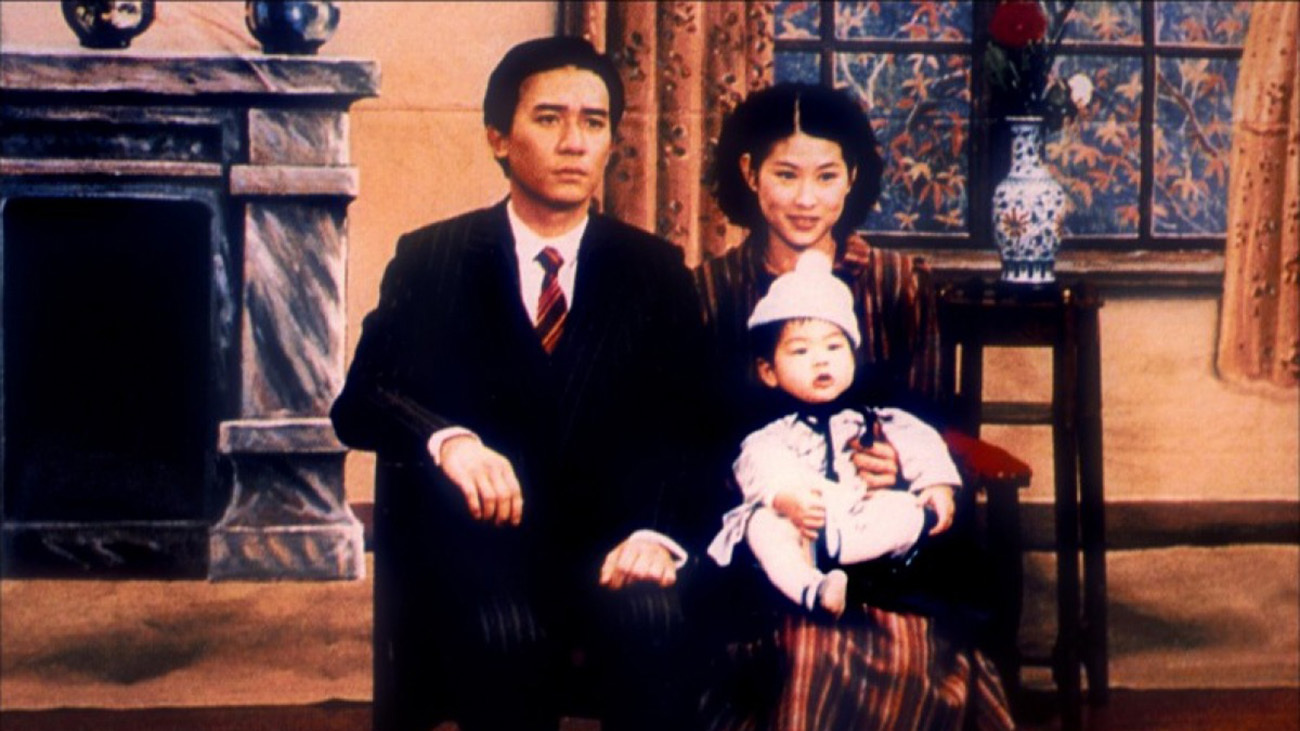

4. Spring In A Small Town (1948) – Mainland China

“Spring in a small town” is considered by most film scholars as the greatest Chinese film of all time, and by Wong Kar Wai as the greatest film of all time.

Directed by the often overlooked auteur Fei Mu, the film is set just after the second Sino-Japanese War (1937 – 1945) in a ruined family compound and effortlessly depicts the frustrations caused by a complex love triangle.

It is about a woman who has to deal with the tensions of re-encountering her ex-lover, whilst nursing her sick husband. The woman played by Wei Wei, fell out of love with her husband years ago, but even without the pressures of society the guilt alone prevents her from following her heart.

Delicately and subtly, “Spring in a small town” demonstrates the full potential of cinema. It burrows past the calm exteriors of the human face and exposes the sorrows that linger within.

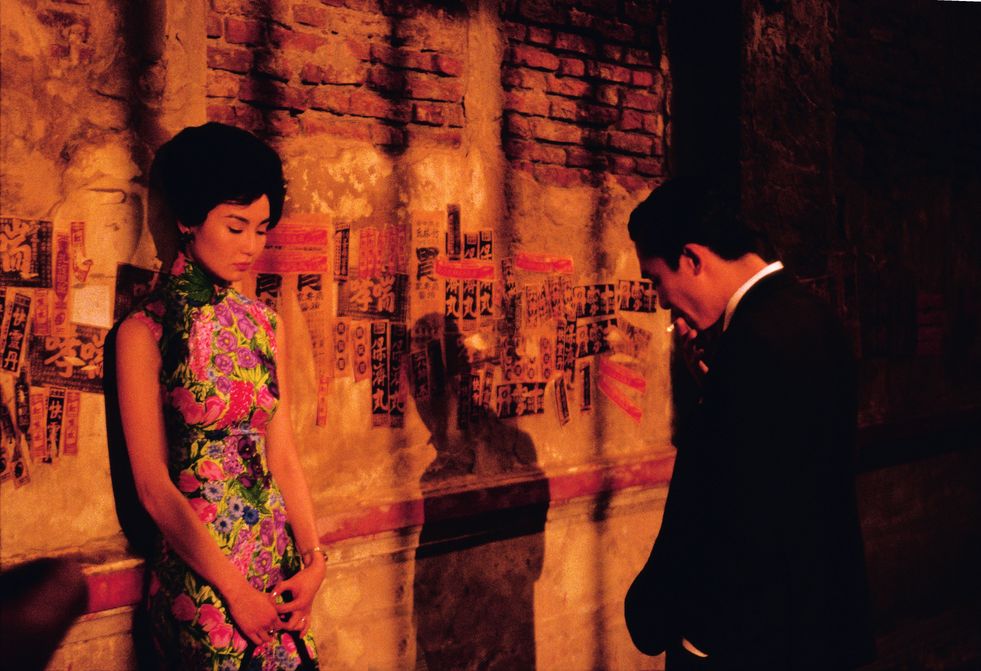

3. In The Mood For Love (2000) – Hong Kong

“In the mood for love” is a film that gets better after every viewing and is cited in countless polls as the greatest Chinese-language film ever made. When Wong Kar-wai’s masterpiece was originally released in 2000 it was referred to as ‘the Chinese answer to David Lean’s “Brief Encounter”’. As bold of a statement this is I feel “In the mood for love” is the superior film (I can feel the rage from David Lean and Celia Johnson fans at the mere thought of it).

The film is a flip on the “Brief Encounter” concept, Instead of two married people almost having an affair, this is about two people that find out their spouses are actually having one. The film flows like music, it is strikingly poetic and lyrical. Subtext and nuances are executed to such an advanced level, the likes of Anton Chekhov would have been proud to call it their own.

The music in the film is not used to influence emotion, but to capture a time and place that only existed between the two protagonists. A place few words can express and only few art forms can reveal.

2. A City Of Sadness (1989) – Taiwan

“A City of Sadness” is arguably the greatest film ever made and its director Hou Hsiao-hsien is without question one of the most important auteurs of modern times. Hou was one of the key figures of the Taiwanese New Wave (1982 – 1990). With his trademark distanced cinematography and restrained poetic naturalism, he has influenced filmmakers from Olivier Assayas to Joanna Hogg.

The film deals openly with the harsh transgressions the Kuomintang (KMT) inflicted during the 1945 handover of Taiwan from Japan. It was the first film to address the ‘228 incident’ of 1947, which resulted in the massacre of thousands of people.

It is a landmark not only for its cinematic excellence, but its immense cultural significance regarding the historical and social identity of the Taiwanese people. As with most Hou movies from the 1980’s they resemble the aesthetic gentleness of Japanese masters like Yasujirō Ozu and Heinosuke Gosho. Like them, imbedded within the films poetic stillness “A City of Sadness” grinds into the quiet sorrows of its characters in a way that would have made Ozu himself proud.

1. The Goddess (1934) – Mainland China

The second generation of Chinese cinema mostly consisted of communist/leftist propaganda films, attacking capitalism and rich landowners that made poor people’s lives a misery. Despite some interesting techniques, the majority of these films were ‘slightly overstated’ with their propaganda sentiments (to say the least); however there were a handful that got the balance between political obligation and cinematic brilliance just right.

The most famous of these was Wu Yonggang’s masterpiece “The Goddess”. Typical of a second generation film it shows the devastating effects of capitalism, but does so in a subtle and relatively unsentimental way.

Chinese silent mega star Ruan Lingyu plays a prostitute working on the Shanghai streets in order to support her young child. The film forms a contrast between the seductive prostitute of the night and the loving mother of the day.

Author Bio: Matthew E Carter is a British world cinema blogger and part of a filmmaking collective called Black Country Cinema. His work usually focuses on documentary and East Asian cinema; primarily Taiwanese, Japanese, Chinese and Cantonese.