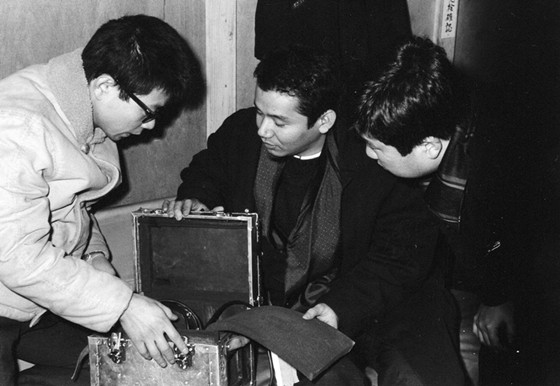

14. A Man Vanishes (Shohei Imamura, 1967)

Most documentaries are constructed as a way of unveiling “facts” in stories where most the world have accepted the “legend.” Shohei Imamura’s A Man Vanishes is not really about the disappearing man at its center, but more about the legends created by those around him. In reality, when someone disappears all we are left to do is reconcile the lives we continue to lead, maybe making the trauma about us rather than about the vanishing itself.

A Man Vanishes turns this on its head by questioning the nature of reality and fiction in following the desperate pursuit of the man’s fiancé. At one point the fiancé’s sister says she hopes her sister will just, “forget about Tadashi [the missing man].”

Imamura directs A Man Vanishes with a narrative filmmaker’s eye, even adding off-beat quirky music to a moment where the family goes to a psychic. And the second half of the film shifts into uncertainty about what we are seeing, as the central relationship, the man, the fiancé, and Imamura himself is called into question.

One must wonder if everything we’ve witnessed to this point has been a serious mockumentary. No matter, Imamura’s approach remains radical and effective as it’s less about the stakes in finding someone as it is about how a narrative is fashioned in the aftermath of something people can’t understand.

13. Koyaanisqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 1982)

Even if you’ve never sat down to watch Koyaanisqatsi, chances are you’ve seen its images. Perhaps not literally, but the this early-80s film has managed to influence everything from music videos and computer commercials to CGI-driven blockbusters. Koyaanisqatsi was conceived as a collaboration between first time director Godfrey Reggio, cinematographer Ron Fricke, and composer Philip Glass.

Ostensibly it’s a montage of the world that takes the viewer from the beginnings of nature to the restlessness of modern existence. Though beyond it’s “coming-of-age” structure there’s also a streak of cynicism that’s tipped off by the title’s very translation: “Unbalanced Life.” Koyaanisqatsi is a word from the Hopi Language, put to the film after Reggio’s initial idea to give it no title was resisted.

This isn’t a movie meant only to comment upon the destructive force of technology, but open our eyes to how firmly we’ve been lost inside of it. Whether the highways look strikingly similar to the inside of a computer chip or the large moon gets obscured by a skyscraper, our world here has been consumed by technological forces. Central to Koyaanisqatsi is Philip Glass’ multi-layered score. While not as memorable as his work in Errol Morris’ The Thin Blue Line, Glass’ speedy cacophonous designs are arguably more powerful as they go toe-to-toe with Reggio’s rapid images.

A documentary by definition, Koyaanisqatsi employs extremely cinematic filming techniques. Beyond the well known fast motion, there’s also helicopter aerials, pans, cranes, time-lapses, and dollies. If documentaries are meant to capture life in the moment, Fricke’s camera almost certainly conducted take after take to get that moment right. However, even this cinematic approach speaks less to manipulation and more to the sameness of our world, again furthering Reggio’s themes.

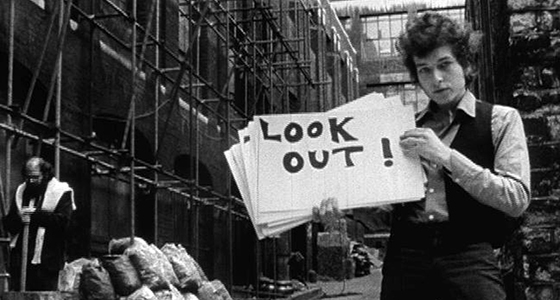

12. Don’t Look Back (D.A. Pennebaker, 1967)

Bob Dylan is a living myth. A person only made more complex when he sits in front of a microphone and croons with the soul and vigor of a man who wouldn’t seem capable of even the slightest put on. That central paradox is what makes D.A. Pennebaker’s fascinating 1967 portrait tick. Never in its running time does it become entirely clear when Dylan himself appears and when his sunglasses-wearing performance kicks in.

So fluidly does the star stay in a – perhaps crafted, perhaps honest – character, that his interactions are even more fascinating. At one otherwise normal moment, Dylan is introduced to two brothers, each named Steve. Another celebrity may have charismatically called attention to the oddity. Instead, Dylan seems not to even notice.

Pennebaker’s shooting style remains unobtrusive, instead prioritizing details. The camera often catches Dylan’s eyes, fingers around a guitar, or awestruck stares of the many gawking onlookers. Don’t Look Back may be the first “behind the scenes” documentary to look at the stress an artist endures on the road while attempting to maintain an image. For Dylan here, it is the measured image of a snide asshole.

He plays it to full tilt, as when he systemically picks apart the inferior musical talents of Donovan or the monotonous questions of a university student. As we have come to realize, we may never know the real Dylan and Don’t Look Back is no help.

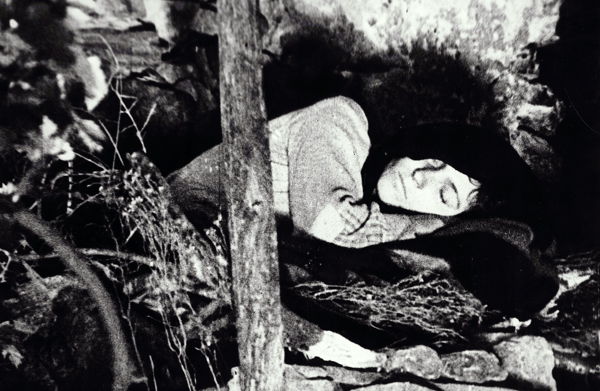

11. Land Without Bread (Luis Bunuel, 1933)

In a time when socially conscious documentaries are being produced by the thousands, Land Without Bread (Las Hurdes) still stands out for its scope and scathing dark humor. Made by the great Spanish filmmaker, Luis Bunuel, the film captures the daily lives of people living in a deeply impoverished region of Spain known as Las Hurdes Atlas.

The title speaks to the infertile soil that makes bread a scarcity as residents must subsist on pork or whatever other meats they can hunt. Known mostly for his surrealist films, Land Without Bread remained Bunuel’s one and only documentary. It is no less the indictment of class discrepancy than his later works would become known.

Exploring topics such as disease, hunger, and mental illness, Land Without Bread was the first film to turn its lens onto the parts of culture that a major nation was attempting to keep hidden. As was often Bunuel’s style, the visual approach is straightforward and honest, if sometimes also wry and off-beat. Like Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North, Bunuel blurred the lines between fiction and reality by freely manipulating events.

At one point, the crew went so far as to shoot a goat off a cliff in an effort to film its fall. In those days this was hardly a frowned upon practice. Yet, it does call attention to the fact that early nonfiction filmmakers were already seeing the medium as an extension of its narrative counterpart rather than an opposite.

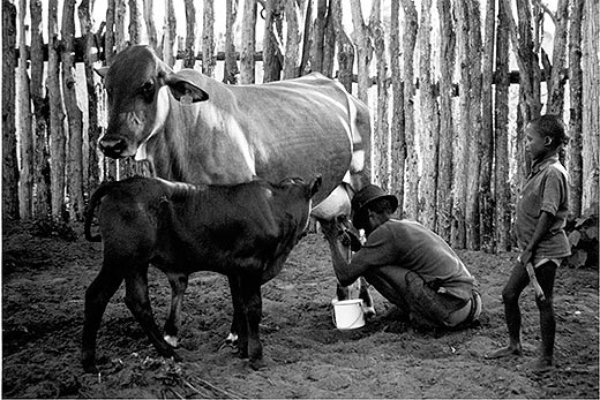

10. The Hunters (John Marshall, 1957)

Most compelling documentaries, in some form or the other, are dealing with the compression of time; attempting to shave life down to two or three manageable viewing hours. Some, such as Claude Lanzman’s Shoah, need extensive time to development their array of threads or characters. Few, however, use temporality as a main component of storytelling. John Marshall’s The Hunters explores survival in a Namibian Desert by following four Kung men on a Giraffe hunt.

The majority of the 72-minute running time is concerned with the hunt itself. Unfolding in real time, we get to feel the optimism in early campfire nights and eagerness to provide for an entire tribe that will, upon failure, go starving. As the hunt goes on, our own desire to capture a large animal starts to grow. As food runs thin and exhaustion sets in, the stakes raise. It’s all done as if we are there with the !Kung men in the moment.

It isn’t so much that The Hunters actually unfolds uncompressed because the lengthy hunt is still carved into just over an hour. It is that Marshall’s ability to keep the viewer present takes us into the minds of the four main subjects. In another film, the grueling final hunt of the huge giraffe might play as a terrifying murder. After all, this harmless animal is being taken down right in front of our eyes.

We see its pain and torture in the final inevitable moments its life. But the naturalness with which the hunters approach their prey – a homemade spear rather than a gun – and the size of the animal compared to its captors, keeps a viewer enraptured and on the side of the men as well as the people they will save. The Hunters is an ethnographic film – a raw, gritty, unmanpulative one – while also a study in nuanced suspense and pure cinematic stakes.

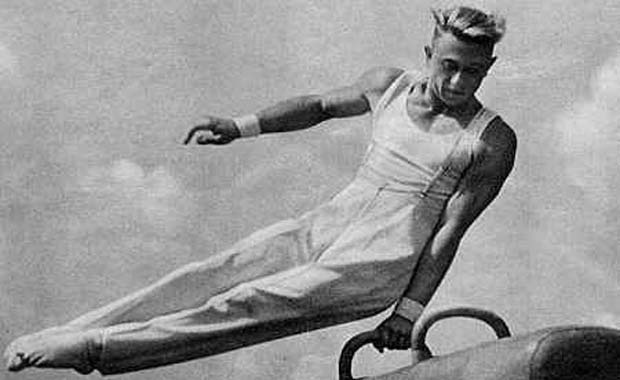

9. Olympia (Leni Riefenstahl, 1938)

Leni Riefenstahl’s films will forever live in the long dark shadow the Nazi regime that they propagandized. It’s a testament to Riefenstahl’s unique imagination that even with that dubious distinction her work has been lauded as a valuable source of reference and inspiration. Expanding upon Dziga Vertov’s use of cinema verite mixed with unexpected editing choices, Riefenstahl included yet unseen smash cuts, jump cuts, extreme close-ups, and surprising camera angles.

Her 1935 film Triumph of the Will, which placed Adolf Hitler on a holy level of leadership, has been hailed as a landmark of the agenda-driven documentary; at least in terms of form. Olympia, her follow-up, is the first feature-length documentary to capture the Olympic Games. However, instead of simply filming the events, Riefenstahl turned them into a vehicle for rousing entertainment, assuring that sports would forever be indicators of international strength and glory.

Olympia may be the single reason that sports went from feats of athleticism and recreation to utter spectacle. Broadcasting as diverse as professional wrestling and talk shows has employed techniques developed by Riefenstahl. Even live events have adopted camera angles, along with musical accompaniments and opening montages, spawned from Olympia.

Made in part to show Berlin, the host city, as a mecca of health and prosperity, Olympia also highlighted specific athletes on a grand scale. This coming during a time where celebrity athletes were reaching fans only on local levels. Perhaps most famous, and unlikely, is Olympia’s positive spotlight on African American sprinter Jesse Owens who, to the chagrin of the Germans, took Berlin by storm. Owens would became the shoulders on which the Allies could stand, at least for a moment.

8. F for Fake (Orson Welles, 1974)

Above all else, Orson Welles’ F for Fake is a stunning feat of montage editing, unabashedly gleaning from a variety of sources to create a patchwork about the value of art itself. Not exactly a documentary of the classic sort, though too ungainly to be classified an film, Welles uses his patented campfire-storytelling voice to lend both narration and personal flavor.

The story, at least on the surface, tells of an art forger named Elmyr de Hory and his real life biographer Clifford Irving, who was also the notorious hoax-biographer of mysterious Hollywood mogul Howard Hughes. As Welles ponders, this could make de Hory a “fake faker.” The result is a film that is meant to fold in on itself, never precisely a constructed narrative or nonfiction investigation. The point being that art is only as real as the value assigned to it, like a Michelangelo painting versus its copy.

Buried only skin deep within all the structural playfulness is a searing social commentary wherein Welles takes shots at so called experts, who not only wouldn’t know a fake from an authentic, but wouldn’t “want to know the truth.” Also called to task is a culture whose belief in illusion makes them susceptible to trickery, often in the name of commerce. Welles, in F for Fake, uses the documentary form to its fullest capacity by experimenting with approach and speaking out about the world’s willingness to turn a blind eye to, if not openly applaud, fakery.