7. San Soleil (Chris Marker, 1983)

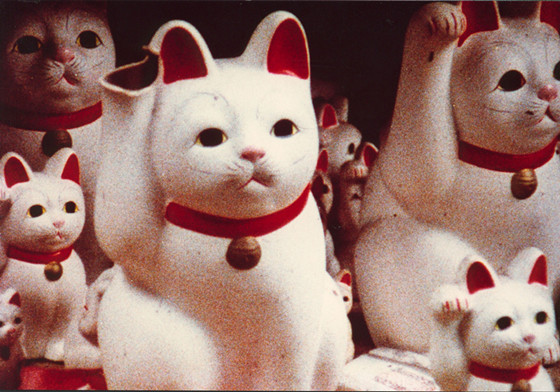

Released the same year as Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi, Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil similarly uses non-diagetic sound and montage as a way to communicate feelings about the changing world. Marker, that great mercurial outsider of La Nouvelle Vague, is no less skeptical of modernity, even as he relishes in the beauty of its banality. A travelogue and film told to us by way of a letter written by a man who has moved from the two extremes of Japan and Guinea-Bissou.

While most films of this kind might recount the travels, San Soleil instead becomes a meditation on the nature of human memory. Without context, memory fades, images persist even if the actuality does not. Sans Soleil sets out to express how this unbalanced view has often affected personal histories and even global policies.

The haunting score seems ripped from a dark sci-fi film, underlining the disrupted peace contained in a forgotten natural existence. Marker even goes so far as to turn movement into Poltergeist-like infrared swaths of motion. Something existed there, only we have no way of knowing who, or remembering what.

Furthermore, using scenes from Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Marker expresses the frustration that comes from getting lost inside fragmented memory, explaining that he has visited each of the filming locations, though with the constant reminder of “Or maybe not,” one must wonder if that too has been made up. When we watch a film, it’s easy to be transported to another place. This, Sans Soleil explains, may be no different than showing up for real. Most memories cannot be captured, even with the assistance of a motion picture camera.

6. Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

As much an experiment as a documentary, Dizga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera is the product of Soviet montage technique and social commentary. Unabashedly using a style full of split screens, superimpositions, wild camera angles, and speedy edits, Vertov’s efforts to take chances exemplify that cinema is capable of anything. The story itself concerns a look at Soviets as they go about their work and normal activities.

The cameraman of the title is actually the film itself, as if calling attention to the idea that these entire experiences are being manipulated by a creator. Like Eisenstein’s early films, Man with a Movie Camera is memorable as much for its boundary-pushing as it is for its social intentions.

The speed of advanced technology is carefully chosen to portray a Soviet city of the future. A city where industry reigns, life is fast and exciting, and the rest of the world can be in awe. This isn’t a film meant to capture life as it occurs in front of the camera, but a picture meant to turn it into an idealized life that could happen at some point. Like many films to come, Vertov had an intention with his “nonfiction” so staging and editing were crafted to suit that beginning goal.

Unlike many documentaries, the desired end wasn’t to show us a certain type of reality, as in the Inuits’ lifestyle of Nanook of the North or poverty in Land Without Bread, but to show a place that never existed at all. As such, Vertov may have ushered in the idea of the propaganda film, soon to be used to full effect by Leni Riefenstahl and the Nazis.

5. Nanook of the North (Robert Flaherty, 1922)

Nanook of the North may not be the first documentary as is often claimed but, like Birth of a Nation did for narrative cinema, it laid the groundwork for what the form would become. Shooting in Port Harrison, Northern Quebec, director Robert Flaherty set out to capture one year in the lives of Inuits. Due to filming conditions, Flaherty staged and recreated multiple scenes. As a result, Flaherty not only was the first to introduce the concept of recreation (though it wasn’t formally stated within the film), but also much of what we’ve come to accept from unscripted television and movies.

The success of Nanook, however, has less to do with its execution and more the subjects themselves. Tucked within the scenes of survival are moments meant to show humanity. Like Land Without Bread, this is a place yet to be touched by greater civilization. Flaherty smartly relates not only the struggles of primitive life, but also shows how similar they are to everyone else. One particular scene is staged by showing children playing after a title card reads, “While Father Works…”

We then see the father carefully building an igloo. Later, candlelight and an obviously unfinished roof (as no exposure could legitimately be gained) take us inside normal family life under this “new” shelter. In recent years, Nanook has been criticized for its manipulation and protracted spectacle, though watching the film one is hardly bothered. Its innovations transcend authenticity and layout much that has come since.

4. Grey Gardens (Maysles Bros, 1975)

Today, Grey Gardens’ legacy precedes it. Long before it was an HBO special or a hit Broadway play, it was a modest documentary by two of America’s nonfiction pioneers, Albert and David Maysles. While signaling a peak in the Maysles brothers now much-lauded Direct Cinema canon, Grey Gardens may also be the duo’s most restrained effort. What makes it so compelling are the charismatic subjects, Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale – socialite and aunt of Jackie Kennedy Onassis – and her eccentric daughter, Edith Bouvier Beale. “Big Edie” and “Little Edie” make the most of their performance, at times literally playing for the camera while at other times being completely oblivious to it.

At no point do their connective energies, at once deeply saddening and moving, make the “fly on the wall” camerawork feel dull. Direct Cinema may be seen as an unobtrusive choice, but in none of their films do the filmmakers fail to make their presences known. In fact, the process can often be as important to the films’ constructions as the moments they capture. Gimme Shelter famously sat Mick Jagger in front of a moviola to watch footage from his tragic Alatamont concert. Here the most iconic image shows Albert (the cameraman) turning to a mirror to film himself holding his camera.

The two idiosyncratic women are front and center, but also the titular estate is rendered as a Great Expectations-like lair of former prestige. Holes in the walls, Raccoons making nests, and ivy eating up its sides, this is nothing near the grandiose setting it once was. It would be easy to see this as a comment upon the decay of old money, if also a metaphor for an America that has long lost its Golden Age.

Both readings are apt. But the film transcends easy categorization because of the Maysles’ compassion for these subjects, specifically Little Edie. The daughter, always wearing a headdress to hide her alopecia, sings, dances, and proclaims herself a performer. There’s a tremendous amount of delusion, no doubt. However, Grey Gardens puts her obvious charm on display. It may be nonfiction, but there’s a good bit of theatre.

3. The Thin Blue Line (Errol Morris, 1988)

The Thin Blue Line wasn’t Errol Morris’ first film, but it was the one that in a short burst of investigative documentary announced his presence to the world. How did he do it? For one, by exploring the very theme of truth head-on. It is, after all, a film about lies and liars. Next, the picture happened to exonerate a man on death row by assuring the police work was shabby and the convicted man innocent.

It also happens to be a film that used re-enactments, formerly a poorly hidden form of manipulation or stodgy history class demonstration, in the most cinematic way we’d yet to have seen. Morris didn’t hide that he was recreating scenes. He made movies out of them. Having not seen The Thin Blue Line upon its initial release, I can’t say for sure if the film came on with the lightning rod effect of an entire medium turned upside down. Knowing what came before, it sure as heck looks like it.

Morris’ first brilliant choice was to make the re-opening of a closed case into a piece of pure entertainment, from the aforementioned cinematography right down to Philip Glass’ mesmerizing music. There had been traces of this in documentaries before, such as Peter Davis’ overt Hearts and Minds, but nothing quite like what Morris had in mind. The characters here look right into the camera lens. We aren’t allowed only to watch them, but they are also watching us.

Looking into the eyes of someone forces a need to tell a strong version of the truth. This has been Morris’ style from day one and the results are magnetizing. Like Hoop Dreams, Morris also had a bit of luck in that he put his faith on a case that actually turned out to possess a wrongful conviction. However, had this not been true, Morris’ eye and ear for idiosyncratic characters would have made just the investigation a fascinating experience. You wouldn’t be wrong to assert that documentary as we know it today began with The Thin Blue Line.

2. Hoop Dreams (Steve James, 1994)

In the early 90s, Steve James and Frederick Marx set out to make a 30-minute PBS documentary about two promising young basketball players. It was meant to be a snapshot of the process, competition, and glory of inner city hoops. Four years later, they had the most earnest portrait of sports culture America had yet to see.

Of all that sets documentaries apart, perhaps nothing is more crucial than a good bit of luck. Not to say luck doesn’t play a role in all types of art, but in a film like Hoop Dreams luck takes on an almost spiritual resonance. The picture would likely have always been a powerful socio-political document for our fame-obsessed time, even had it not turned in twists and turns that even a seasoned screenwriter couldn’t have penned. That those surprises seem to unfold realistically throughout its three-hour runtime only heightens its impact.

While it’s easy to gush over the happenstance, Hoop Dreams is first and foremost a breathtaking sports movie. Fit with a build up to insurmountable obstacles, difficult opponents, and life or death match-ups. Yet, the film is also a call to action about what may become of culture that fantasizes about trivial dreams without allowing realistic goals to develop. Except James never gets didactic about a mission statement, even perhaps suggesting that class and racial disparity may never be conquerable. Which is not to say the film doesn’t make clear the filmmakers are hardly on the side of a system that sees urban youth as either a path to profit or a throwaway.

Above all, humanity triumphs in Hoop Dreams. As in one scene where Arthur Agee’s mom talks about attending nursing school while laying down due to a bad back. William Gates, the golden boy-turned-bust, sums it up best when he tells the camera, “When somebody say, “when you get to the NBA, don’t forget about me,” and that stuff. Well, I should’ve said to them, “if I don’t make it, don’t you forget about me.”

1. Shoah (Claude Lanzman, 1985)

Perhaps it’s only human to absolve one’s self of responsibility in an effort to forgot catastrophes of the past. After all, there’s always someone worse, more at fault, or in the middle of a situation, for whom we can point a finger. Claude Lanzman’s landmark epic, Shoah, puts not just the atrocities of the Holocaust under a microscope but the mechanics with which humans can move from a place of righteousness to evil and then, in only a small matter of time, recontextualize such evil so as to make it hardly exist at all.

Shoah sets out to let nobody off the hook. To do this, Lanzman interviews various people involved in multiple ways with the Holocaust. The results are alarmingly straightforward and honest, without the crutch of explaining who’s, why’s, how’s, or stuffy historical facts. Shoah is blunt, rough, and enlightening.

The length of Shoah, a relentless 8 hours, works not only to exhibit the breath of the individual subjects but also to create a collective. This isn’t about only them, but about humanity. Shoah need not be viewed all at once, though fascinating as the parts are, they take on even greater resonance when viewed as a sum. Something suffocating and inescapable forms upon watching Shoah, like we are beginning to understand that the response to any disaster, no matter how seemingly distant from our own lives, should be to look in a mirror and assess how we each took part.

Author Bio: Zac Petrillo is a graduate of Chapman University’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts. A New York City native, he currently writes and produces fiction and nonfiction film and television out of Los Angeles. Follow Zac on Twitter @zpetrillo.