14. Southern Comfort (1981)

Set in Louisiana in 1973 in the bayou, the film also owes something to the theme of the outside encroaching on the territory of rural inhabitants. Speaking to a black southern guardsman about some prostitutes he has procured for some of his fellow guardsmen, Spence (Keith Carradine) says to Cribbs (T.J. Carter), “the purpose of the National Southern Guard is to keep you darker brothers away from decent southern women; however, in the spirit of the new South, I have made full arrangements.” Nevertheless, the film isn’t about race so much as it is class.

As with Deliverance and Hunter’s Blood, the problem arises when outsiders (read middle class and white) invade the lives of those who live off the land and the subsequent violence stems from the disrespect the National Guardsmen show toward the locals when they “borrow” their canoes and then fire blanks at them as Cajuns stand silently and ominously watching from the water’s edge. When Poole, the commander in charge of their unit, is shot by one of the Cajun men, the seriousness of the situation becomes evident.

The viewer is asked to identify with the guardsmen’s point of view. Their behavior is rarely criticized by the men themselves, and it takes on an air of moral and intellectual superiority wrapped in self-righteous anger. The men pay for their intrusion as they are systematically murdered in a variety of ways that resemble the guerilla warfare of the Vietnam War.

13. Deliverance (1972)

This is one of the best known and notorious Southern Gothic movies on the list, with stereotypes of southerners that have made their way into the popular imagination because of the film’s indelible sequences of violence and representations of what some backwoods southerners look like and sound like.

The story of four middle class men who take a camping and hunting trip on the Arkansas River turns into an unexpected horror adventure story. While there is a subset of horror films that focus on violence and sexual assault against women—known as rape revenge movies—Deliverance is one of the few that focuses on male-on-male sexual violence.

Over a decade later, the film Hunter’s Blood would revisit many of these themes found in Deliverance. The famous dueling banjo sequence that occurs before the men begin their trip now connotes impending violence and struggle, poverty and squalor, and inbreeding and stunted intellectual development.

The literal and figurative violence depicted in the film ultimately expresses the horror and fear that city dwellers have of country folk and how justice is meted out in a world that seems disconnected from city laws, lawyers and courtrooms.

12. Angel Heart (1987)

A classic neo-noir from the late 1980s: the setting is 1955 and moves from New York to New Orleans. Mickey Rourke plays Harry Angel, hired by Louis Cyphre and played by Robert De Niro, to find a man named Johnny Favorite because of a debt the man owes Cyphre.

The film was controversial when it was released in part because of its graphic scenes of sex and violence. New Orleans, the voodoo capital of the United States, is the place where the religion of voodoo (a confluence of African slave trade practices and Catholicism) is explored from the viewpoint of its city’s native inhabitants.

The film raises issues of the tension between faith, belief, death and the very nature of the soul. One of the most memorable scenes in the movie, one that foreshadows the character of Cyphre and his relationship with Harry, takes place in a restaurant where Cyphre discusses that symbolism of eggs and the human soul as he rolls a hardboiled egg on a plate and slowly eats it.

When Harry confronts Cyphre for the last time, he says, “I know who I am.” This is followed by a series of flashbacks that challenge what the viewer ‘s knowledge of preceding events and the mystery Harry has been trying to solve is finally revealed.

11. Wise Blood (1979)

Brad Dourif as Hazel Motes brings to life one of Flannery O’Connor’s strangest characters. He has the zeal of a preacher without identifying as one: “Nothing matters but that Jesus don’t exist,” he says. After a stint in the Army, Hazel drifts to a small town where he hopes to start a new church—a Church of Christ without Christ.

Through flashbacks of Hazel as a young boy, the viewer gathers glimpses of his traumatic childhood as the grandson of a preacher (director John Huston) and how he has been shaped into a man who yearns for something to believe in that isn’t Christ-centric. Even though he claims “I don’t have to run away from anything because I don’t believe in anything,” his attempt to carve out his own personal doctrine of belief and spirituality is an existentialist desire for truth and self acceptance and independence devoid of religious doctrine and moral hypocrisy.

O’Connor’s perverse humor and grotesque characters also include Enoch Emory as a lost young man also searching for something to believe in, whether it be the shrunken body of human or the need to run around in a gorilla costume; Asa Hawks as a shyster preacher who pretends to have blinded himself for God; and his daughter Sabbath Lily Hawks who forms a bond with the shrunken body and seeks a physical relationship with Hazel.

The film is both a humorous and earnest attempt to understand the place of religion in a modern capitalist society, where people seek to align themselves with something, anything to give their lives meaning.

10. The Heart is a Lonely Hunter (1968)

“I like freaks,” says the owner of The New York Café in Carson McCuller’s 1940 novel, set in a small southern Georgia mill town. As in most Southern Gothic stories, freaks and outcasts populate the page and screen. What’s notable about the novel and the film is the sensitivity in which the characters that exist outside of the norm of the rural south are depicted. These characters include Singer, a deaf mute; Dr. Copeland, an intellectual and black doctor; Biff Brannon, the owner of the town restaurant; and Mick, the young tomboy.

One of the central characters, the deaf mute Mr. Singer, becomes a sounding board for the others, enabling them to vent all of their anger, fear and frustration about their inner lives and their attempt to understand the world around them. However, his own needs remain hidden to others, mainly his love for his friend and fellow deaf mute, the Greek Spiros Antonopoulos. The narrative allows the characters to embody the hopes and dreams of a landscape that is stifling and ultimately bleak.

The film, and especially the novel, depicts one of the most complex, rounded characters in the person of Dr. Copeland, the only black doctor in town. It shows his difficult struggle as he straddles the divide between the communities of white and black, never really fitting into either. When tragedy strikes Singer, the peace that he provided to so many people is disrupted. The film, unlike the novel, ends with Mick and Dr. Copeland saying farewell in a cemetery. Each going their separate ways in a semblance of optimism and inner renewal.

9. Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964)

As Bette Davis got older, she was increasingly relegated to films in which she played characters who were morally grotesque and sometimes physically repugnant—What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? and Dead Ringer being two prime examples. In Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte her character might or might not be guilty of the gruesome murder of her lover that took place years before in the family plantation home.

The film boasts an impressive cast of older Hollywood stars including Bette Davis, Olivia de Havilland, Joseph Cotton, Mary Astor and Agnes Moorehead. Robert Aldrich directed this in the hopes of rekindling his success of Baby Jane by reuniting Joan Crawford and Bette Davis. Davis and Crawford, known for their animosity toward each other, took turns trying to out stage the other, ultimately leading to Crawford being replaced by de Havilland.

Charlotte (Davis) and Miriam, Charlotte’s cousin (de Havilland) are constantly at each other’s throats and the tension of distrust and animosity, which is largely based on the goal of proving Charlotte insane, provide much of the campy elements in the film. Mary Astor as Jewel holds the secret to the family tragedy. Agnes Moorehead’s performance as the bizarre housekeeper is not to be missed. The ending is hilarious and extremely satisfying.

8. Baby Doll (1956)

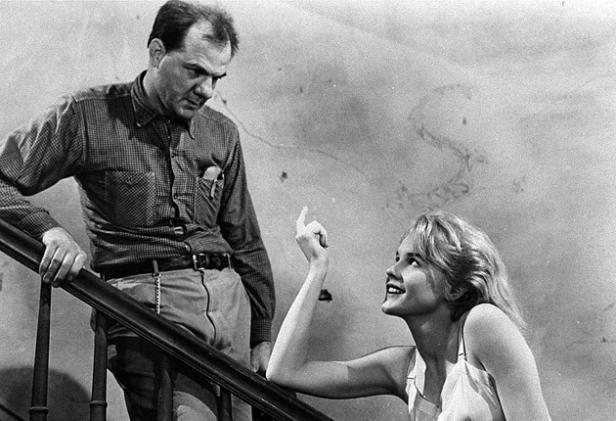

This is another Elia Kazan production of a Tennessee Williams’ play. The film opens with a scene of voyeurism as Archie Lee (played by Karl Malden) spies on his much younger wife called Baby Doll. This strange scene becomes stranger as the viewer sees Baby Doll sleeping in a crib and sucking her thumb. Archie Lee and Baby Doll have been married for a couple of years but have never had sex, which she promises to have with him on her twentieth birthday. T

he couple lives in a dilapidated southern mansion in a town called Tiger Tail. Archie Lee and many other men in the town have been put out of the cotton business by the Sicilian Silva Vacarro (Eli Wallach). The drama unfolds after Archie Lee burns down Vacarro’s mill and Vacarro, who suspects him, shows up at his place to seduce and interrogate Baby.

In a humorous moment of sexual innuendo between Baby and Vacarro, Baby says to him when offered a pecan he’s just picked from the ground: “I wouldn’t dream of eating a nut in which a man had cracked in his mouth.” To which Vacarro rejoinds, “You have many refinements.” The film depicts the vacillations of fortune, opportunity and desire in the course of a day, leaving most everyone not much better off than when the story opens, except perhaps a little wiser.