8. Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984)

In Competition in 1984: The Element of Crime, Ghare Baire, Quilombo, Success is the Best Revenge, Under the Volcano, Where the Green Ants Dream and more.

It may not evoke much of the most well known Paris, or even filmed in the actual Paris, Texas in the title, and resemble more of an odd space landscape at times, but Wenders’ meditation of family coming together and apart is harrowing.

The mysterious tale starts with an amnesiac who wanders the desert in South Texas coming out of it saying nothing to anyone that approaches him, until a phone number is found on his person. The phone number leads to the man’s, Travis Henderson, brother from Los Angeles, Walt Henderson, who travels out to the desert to find him.

Travis has been missing and not heard from at all in the past four years, and Walt and his wife have taken his son in during that time. Travis looks to reconnect with his son, while searching for his wife and all the while travel to Paris, Texas which is where he was told by his mother that he was conceived.

How does the connection of a fractured family, father and son and husband and wife, even begin to come together again after so much time apart? The film tackles that incredulous question almost in parts by finding these lost characters (played with such emotion by Harry Dean Stanton, Hunter Carson, Dean Stockwell and Nastassja Kinski) in Jury president’s Dirk Bogarde’s choice for the festival’s top prize.

7. Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994)

In Competition in 1994: The Browning Version, Exotica, The Hudsucker Proxy, Three Colours: Red, To Live, An Unforgettable Summer and more.

It’s fitting that it was 20 years ago now that Tarantino’s sprawling and chaotic masterpiece not only won the Palme d’Or, but is also screened at on the beaches of the festival in remembrance accordingly. The French and Tarantino have always had a fortuitous relationship; Tarantino credits them for discovering him and they are in love with his love letters to the mediums with references as wide-ranging to B-movies, martial arts pictures and spaghetti Westerns.

With the framework inspired by the actual pulp fiction stories that were the original foundation for film noir stories, Tarantino’s second film follows the interconnected stories of various criminals, low-lifes, mobsters and many other players in the underworld of Los Angeles all with mystery of a briefcase in play (Wallace’s soul? The dangers of nuclear warfare?

The stuff that dreams are made from?). In a stylized, metaphysical and self-referential manner, the film was a dynamic explosion on not only the independent scene that was slowly building itself up since the beginning of the ‘90s, but also for Hollywood and beyond in general.

Pulp Fiction’s influence stretches from the tic-tac aspect of the dialogue (foot massages, Zed’s Dead, the labels of burgers), its stylized format with editing, format, storylines, music, other films and much more. This film, from its inception to its win at Cannes to the Academy Awards, changed the landscape of the field for years to come and still felt to this day.

Even the way actors have approached not only this film, but films afterward; this led to a resurgence of John Travolta’s career, and many others in the cast had their careers given a shot of cocaine to the heart by Tarantino’s manic and lovingly controlled style; Samuel L. Jackson (Jules Winnfield is still the actor’s most popular and recognized role), Bruce Willis, Uma Thurman, Christopher Walken, Ving Rhames, Harvey Keitel, Tim Roth. The film’s energetic cocktail of a diverse cast of all definitions its unconventional makeup made the film a clear winner for Jury president Clint Eastwood to make.

6. Viridiana (Luis Buñuel, 1961)

Adapted from Benito Pérez Galdós’ novel, Buñuel films a scandalous story, as he is wont to do, that was so much so it was banned in Spain by Francisco Franco until his death and the film finally showing in it’s native country in 1977.

The drama circulates around the titular character who is about to complete her vows when she receives an invitation from her distant uncle that she has only met once. Pressured to visit him, Viridiana does and is tied up into various events that escalate in forceful sexual acts – with her striking resemblance to his deceased wife, Viridiana’s uncle dressed her up in her wedding gown and looks to make love to her but ends up hanging himself instead.

Leaving his farm to her, Viridiana abandons her Attempts at nunnery and stays with her cousin Jorge (who too is attracted to her) and his girlfriend Lucia in an effort to educate, feed and take care of beggars and others of lower station than herself.

It’s a film loaded with coded sexual innuendoes, but the film makes its mark and touches on the close conformity that both religion and sex have always had with one another in Buñuel’s famous avant-garde, experimental style.

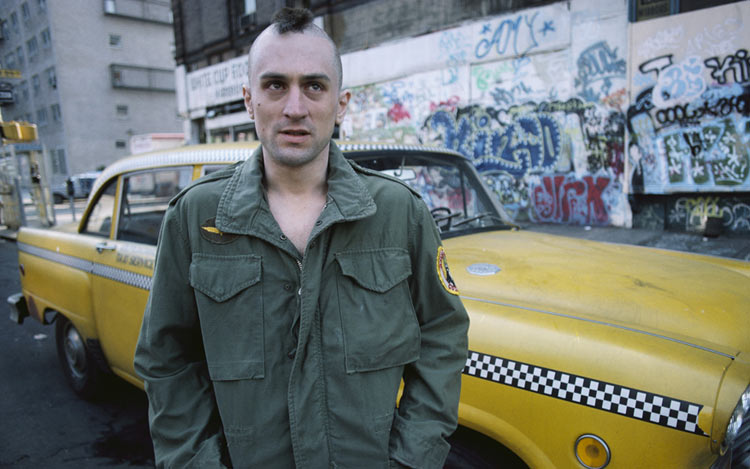

5. Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

In Competition in 1976: Babatu, Bugsy Malone, Kings of the Road, Mr. Klein, Sweet Revenge, The Tenant and more.

“God’s lonely man.” Has there been a more exacting portrayal of loneliness that explodes outward than Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver? Following the depressive nature of Travis Bickle and even more so of New York City’s descent in the ‘70s, Taxi Driver is a raw and angry look into what makes a person who feels like an outsider, an outcast, and how that anger can manifest in so many different ways.

Who are we, who do we want to become and what choices are we going to and willing to make to get there? Those are the questions that plague Bickle, a sufferer of chronic insomnia, as he tries to fill the hole in his life with work as a taxi driver, showings at various adult theatres all while chronicling everything in a diary that he reads (and re-reads, and goes back to correct himself) to the audience.

He seems to find the fulfillment that he is looking for at first by becoming obsessed in wooing Betsy, a campaign manager for Senator Charles Palantine but after she rejects his advances, he sees another to become infatuated with – a child prostitute by the name of Iris. By his own logic, if he saves this young girl from her awful predicament (never mind what she may think of the matter), can he save himself from the hell that he is in?

Exploring alienation in a decade rife with it – from Vietnam to the government, racial relations, women’s lib (as Travis glibly remarks it as), decay from a social standpoint and more – Taxi Driver is slow build of what happens when violence erupts but also the ramifications of that violence as a means to an end.

Featuring a cast in some of their best work in their careers, with Robert De Niro, Jodie Foster, Harvey Keitel, Cybil Shephard and Peter Boyle, the end shows what the fantasy of what we want to look like towards others by achieving our goals. But is that all it is at the end, a fantasy?

Utilizing a creative mix of gritty and also highly stylized violence (the ending shootout is reminiscent of older Japanese samurai films), Scorsese in his usual manner lets the audience decide what is real or not; what is it worth to be recognized by society. What can be done to wash the supposed filth away?

4. Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

In Competition in 1979: The China Syndrome, Days of Heaven, The Europeans, My Brilliant Career, Norma Rae, Woyzeck and more.

The crowning definition of brilliant insanity, or insane brilliance – the 1970s ended for the towering auteur of Francis Ford Coppola in a maelstrom of heart attacks, suicide, setbacks due to weather, war, drugs and Marlon Brando.

Based off Joseph Conrad’s novella, ‘Heart of Darkness,’ Coppola’s effort changes the landscape from the heart of Africa to the heart of Vietnam and how the machinations of modern warfare can change us all. In the film, Captain Willard is charged to go down the Nung River into the deepest of jungle, find the rogue Colonel Kurtz and eliminate him ‘with extreme prejudice’.

On the way towards his psychedelic journey, Willard and his crew comes across the battles of war, involving Colonel Kilgore (an unhinged Robert Duvall), members of a French plantation, Playboy playmates and a cult that embraces the horror of the human psyche.

The problems of the shoot on Apocalypse Now are so renowned that Eleanor Coppola, wife of Francis, led a production of a documentary to showcase how crazy everything was. Harvey Keitel was originally cast as Willard but Coppola replaced him with Martin Sheen who ended up suffering from a heart attack, millions of feet of footage was filmed, the film was delayed numerous of times and most of all, Brando was mercurial in showing up to setup unprepared and overweight.

Despite it all, Brando tailored an incredible and mythological performance, the film breathed the epic scope of it’s aims and Jury president Françoise Sagan made the film the co-recipient of the Palme d’Or along with…

3. The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949)

Considered to be one of the greatest films of all-time (voted number one on the British Film Institute’s Top 100 list), The Third Man is considered to be an all-timer not just in the echelon of cinema, but in the careers of the subsequent players and the film-noir genre as well.

In a twisted tale set in war-torn Vienna, pulp fiction Western writer Holly Martins is looking for his friend that invited him, Harry Lime, while he stumbles (often, quite literally) into a situation where he finds his friend dead, carried off by three men and no one can name ‘the third man.’ Martins becomes involved with Lime’s girlfriend, Anna Schmidt, and all the other assorted players set up by Lime and the new world order on opposite sides of the law.

The film is influential and legendary for a number of its aspects; the use of Reed’s dutch angles, the theme heard throughout the film crafted by Anton Karas using only the zither, the use of shooting on location in Vienna, the underground sewage chase and most of all, the character of Harry Lime.

Saying it was the best role ever created after the war, Orson Welles portrays a memorable character who is at once despicable and callous with human life but also engaging and memorable. From his first appearance on screen, spoiled by a cat, to his speech about cuckoos clocks and dots, Welles’ work along with Joseph Cotten, Trevor Howard, Alida Valli and the rest of the cast offer up a timeless classic.

2. Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945)

Along with Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, when you hear the acclaimed term ‘Italian neorealism’, Rossellini’s harrowing drama is exactly the kind of film the definition applies to.

Co-written by Sergio Amidei and some fellow by the name of Federico Fellini, Rossellini takes a very stripped down and documented approach in crafting the setting of Italy’s world after Benito Mussolini’s fascist reign, after the end of the European theatre in World War II and an overall portrayal of a ravaged continent and where it can go from there.

Combined with the idea of wanting to showcase the history of the people of Rome under Nazi Germany’s occupation, Rossellini crafts a tale of a resistance fighter fleeing from the Gestapo, the efforts of a caring priest (based off a real priest, Don Pieto Morosini, who helped the resistance movement and was captured, executed by the Germans accordingly) and various other characters who try to make the best of their situation in a seemingly bleak and oppressive new world.

True to neorealism fashion, Rossellini peppered the cast with non-professional actors and professional actors such as Aldo Fabrizi, Anna Magnani and Marcello Pagliero, shooting with borrowed and discarded film stock and ending the film on the bleak note of death to the priest at the last second. At the time, it was a bleak world and what more powerful message is there for a film to portray than a reflection of real life?

1. La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960)

That one co-writer of Robert Rossellini’s Rome, Open City that was mentioned before? Turns out he became a very good filmmaker in his own right, and his film in 1960 managed to show that to the entire international filmmaking community.

The title, translated from Italian to be ‘The Sweet Life’ is an expressionistic fable that follows Marcello Rubini who is a journalist who covers a range of topics such as movie stars and their sordid dealings, the cáfe society occupied by the aristocracy and other trifles as he searches for more meaning in life other than what he is doing. This brings him in contact (through seven episodes, including a prologue and an epilogue that the film is broken up in) with an heiress, his own father, an actress, his fiancé, Jesus Christ and many others.

Among inspiring the term that is commonly used now as ‘paparazzi,’ La Dolce Vita plays around with everything that it can with its scope and its structure while exploring themes of religion, narrative, love and others that have made the film a cornerstone of not only the festival, but in film general all over.

Author Bio: A graduate of the Cinema Studies Program at Oakland University, Tobi Ogunyemi is the founder and publisher of SpaceLion, a website associated with the school program and focuses on film analysis, podcasts and other mediums of art. He and the website can be followed at Facebook.com/SpaceLioncs and on Twitter at @spaceliontobi and @SpaceLioncs.