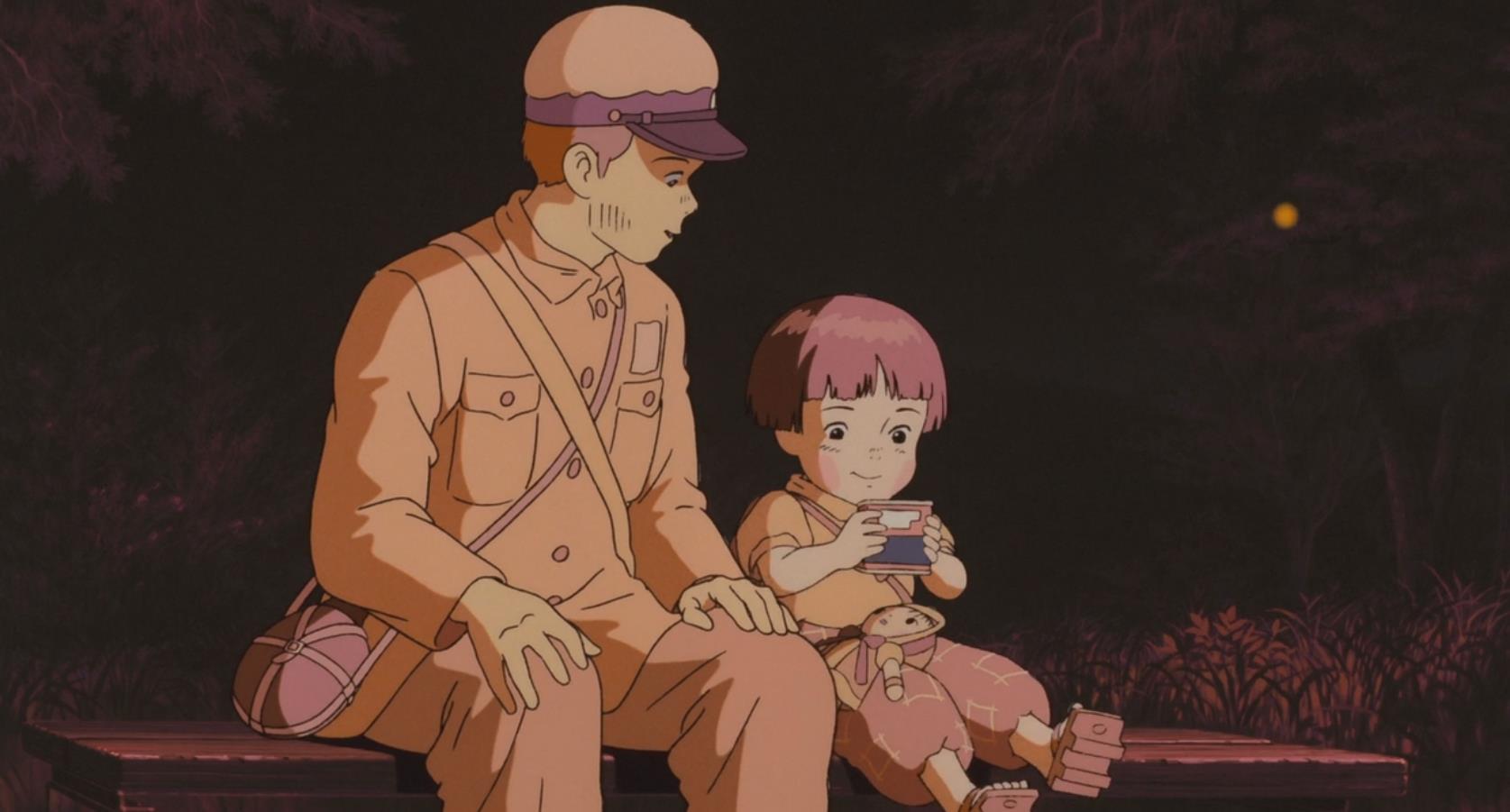

15. Grave of the Fireflies (Isao Takahata, 1988)

Based on the semi-autobiographical novel of the same name by Akiyuki Nosaka, Grave of the Fireflies is a landmark anime and possibly one of the most gut-wrenching films you’ll ever see.

The film opens just after Japan’s surrender in WWII and we see a young boy, Seita, dying alone in a train station. From there on the spirit of the boy explains in flashbacks how this has come to be and the viewer is transported to the firebombing of the city of Kobe by the U.S. a few months earlier. Seita and his little sister Setsuko survive the bombing but their hometown is destroyed and their mother is severely burned and dies soon after.

They are initially taken in by an aunt but as food becomes a very scarce commodity, the woman becomes openly resentful of having the kids around and they decide to run away and start living in an abandoned bomber shelter. What initially appears as an idyllic life in the countryside for the two children soon turns into a nightmare as Seita begins to realise how hard it is for them to survive on their own in a war-torn country without any food supplies.

Don’t make the mistake of dismissing Grave of the Fireflies because it’s an anime. Ranking amongst the best anti-war films ever made, the film is obviously not your run of the mill animated feature and might surprise viewers with its adult and tragic subject matter. Without showing hardly any battle scenes, the movie still manages to be one of the clearest indictments against war and its effects on ordinary people far removed from the front. A masterpiece of Japanese anime, Grave of the Fireflies is a must-see film.

14. The Pianist (Roman Polanski, 2002)

Based on the autobiographical 1946 book Death of a City by Polish-Jewish pianist and composer Wladyslaw Szpilman, which was banned by Polish Communists and out of print until it was re-released as The Pianist in 1998, Roman Polanski’s historical drama was an extremely personal project for the director who himself grew up in Poland during the Nazi occupation and saw most of his family deported to the death camps.

Wladyslaw Szpilman (Adrien Brody) is a pianist from a well-to-do Jewish family in Warsaw as the Nazis invade Poland at the start of World War II. Almost immediately life for Jewish people becomes a terrible struggle as they are forced to wear the Star of David and no longer allowed to work. Initially Szpilman is able to use his reputation as a well respected musician to pull some strings and get work and employment papers for his father but the situation worsens quickly and the ghetto becomes a living hell for its Jewish residents.

Soon after his family is deported to a concentration camp but Wladyslaw himself manages to evade deportation as he is recognised and taken away by an old friend who is now part of the Jewish Ghetto Police moments before getting on the train. He becomes a slave labourer but manages to escape and briefly becomes involved in the failed Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. From there on in, Wladyslaw spends the next few years surviving on his own, moving from one abandoned place to another whilst avoiding the Nazi occupiers as they destroy the city around him.

A stunning and exceptionally moving film, The Pianist manages to capture the horror of the atrocities committed by the Nazis in Warsaw in detail whilst still being able to find moments of unexpected beauty and faith in the human spirit. The film benefits greatly from the central performance by Adrien Brody whose gentle character is an unlikely candidate to survive the circumstances he finds himself in.

Dramatic without ever being overly sentimental and displaying a wealth of good and bad characters amongst the Jews, Poles as well as the Nazis, The Pianist rivals Schindler’s List as one of the most important and best films about the Holocaust ever made. The movie won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, was nominated for seven Oscars, winning three including Best Director and Actor, received seven BAFTA nominations, winning Best Film and Director, as well as seven French Césars including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor.

13. Paths of Glory (Stanley Kubrick, 1957)

Stanley Kubrick’s first genuine masterpiece (although 1956’s The Killing might certainly also be up for consideration for that title too), Paths of Glory is one of the best films about war ever made and like all those best films, it’s a powerful anti-war statement.

During World War I, a French General (George MacReady) orders an attack on a heavily fortified German hill. Knowing full well that the attack will be useless he still proceeds with the orders as he is trying to build his own reputation. The attack is a disaster and the French troops are decimated.

A handful of French troops refuse to leave their trenches and the General, unwilling to admit that it was a horrible idea to begin with, blames the failure on the cowardice of his troops and decided to set an example by executing three of his own men. Their Colonel (Kirk Douglas) takes on their defence but is fighting a losing battle as the powers that be will not lose face and are only interested in saving themselves and finding some scapegoats.

Shot in stark black and white and a documentary-like fashion, Paths of Glory is a scathing indictment of the madness of war and the stark contrasts between those making the decisions and those fighting the actual battles in the trenches.

The film hit some raw nerves and was banned from several European countries, most prominently France, where the film was only first shown in 1975, almost twenty years after it was first released. Truly one of the best movies about war as well as one of the most powerful anti-war statements ever made, this is a movie that should be seen by everybody.

12. The Deer Hunter (Michael Cimino, 1978)

The Deer Hunter was one of the first films in which Hollywood started dealing directly with the Vietnam war, a conflict which had not really been addressed in mainstream cinema yet. Together with Coming Home, which was released the same year and which was one of the movies to compete with The Deer Hunter for Best Picture at the Academy Awards, and Apocalypse Now, which was released the following year, the movie opened the floodgates for films dealing with this touchy subject.

The movie follows a group of friends from a small steelworker’s town in Pennsylvania as some of them are about to go off to war in Vietnam. The film starts off with the wedding celebration of Steve (John Savage) and a final deer hunt before he, Mike (Robert De Niro) and Nick (Christopher Walken) are shipped off to Vietnam. Once there we follow the men as they have been captured by the Vietcong and are forced to participate in brutal games of Russian roulette. The friends manage to escape but Nick gets separated from the other two whilst doing so.

Their war experiences have deeply traumatic effects on all of them as Steve loses his legs and becomes partially paralysed, a severely psychologically damaged Nick remains behind in Saigon and Mike becomes a changed man. When it comes to Mike’s attention after he and Steve have made it back to the U.S. that Nick might still be alive in Saigon, he decides to go find him and bring his old friend home.

Michael Cimino’s second feature was an epic three hour film examining the effects of war on both the men who go off to fight it as well as their loved ones who remain behind. Featuring a fantastic cast which also included Meryl Streep, John Cazale and George Dzundza, the film clearly echoed the general ambivalence felt about the Vietnam war and the disillusionment experienced in its wake.

The film was released for one week in December 1978 to make it eligible for the Oscars and the strategy worked wonders as the movie was nominated for nine Academy Awards, ultimately winning five, including Best Picture and Director. The movie was then re-released on a wider scale and, due to the Oscar buzz surrounding it, became a huge financial success.

11. Schindler’s List (Steven Spielberg, 1993)

Based on the book Schindler’s Ark by Thomas Kenneally, Steven Spielberg’s magnum opus Schindler’s List is a historical drama about the Holocaust and based on the life of Oskar Schindler, a German industrialist and Nazi Party member who nonetheless managed to save the lives of hundreds of Jews.

Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson) is a German businessman in Poland who initially thinks he can make some good money during the war by opening a enamelware factory in Poland. In order to do so he brings in a Jewish accountant by the name of Itzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley) to take care of the administration and “hires” Jewish workers from the Krakow ghetto to supply his factory with cheap labour. For Stern however, getting Jewish people into the factory is a way to save them from deportation.

With the arrival of Commandant Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes), who is sent to Krakow to oversee the construction of the Plaszow concentration camp, Schindler starts changing his mind as he is directly confronted with the commandant’s cruel ways and the execution of many Jews as they are being transferred from the ghetto to the newly built camp.

Slowly but surely he realises that his factory is the only thing stopping the people working there from being killed and starts bribing German officials to get as many Jews as possible working for him and to keep them employed.

Without a doubt Steven Spielberg’s best “serious” film (how does one compare a movie like this to a movie like Jaws?) and one of the best films to have been ever made about the Holocaust, Shindler’s List featured outstanding performances from both Liam Neeson as the conflicted Oskar Schindler and Ralph Fiennes as one of the most terrifying and cruel characters to have ever been captured on film.

Special mention should also go to cinematographer Janusz Kamiński, who succeeds perfectly in giving the film a documentary-like look and manages to make it appear like some of the footage was actually shot in the 1940s.

Schindler’s List was met with virtually unanimous critical praise and ended up being nominated for twelve Oscars, winning seven of them, including Best Picture and Best Director. The movie also won four Golden Globes and Seven BAFTAs in addition to many other awards at international award ceremonies. A monumental film.

10. Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957)

Based on the novel of the same name by Pierre Boulle and the first film where British director David Lean truly decided to go grand scale, Bridge on the River Kwai, which was mostly shot on location in Sri Lanka in gorgeous Technicolor-Cinemascope, redefined the term epic and still stands tall as one of the best and most beloved war films of all time.

Set in Burma in 1943, the film tells the story of a group of prisoners of war in a Japanese POW camp and focuses on the battle of wills between the Japanese camp commander Colonel Saito (Sessue Hayakawa) and the leader of the British soldiers, Colonel Nicholson (Alec Guinness), who initially refuses to help build the titular bridge, which is needed for the Japanese war effort, as officers are exempt from manual labour according to the Geneva convention. His regular men however start work on bridge and try to do the worst job possible in order to not help out the Japanese war effort.

When Nicholson eventually discovers this, he decides that it would be better for his men to build a proper bridge, proving their superiority to the Japanese and thereby boosting morale.

Meanwhile a few men manage to escape, amongst them American Navy Commander Shears (William Holden), who ends up in a hospital in Ceylon and is later volunteered by British Major Warden (Jack Hawkins) to destroy the bridge, setting him up on a collision course with Colonel Nicholson who has become obsessed with constructing it.

Not only considered one of the best war movies of all time but often cited as simply one of the greatest films ever made, Bridge on the River Kwai was nominated for eight Academy Awards, taking home seven of them including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Cinematography for Jack Hildyard whose stunning cinemascope photography ranks amongst the best ever committed to the screen. Additionally the film also won four BAFTA and three Golden Globe Awards as well as a slate of other prizes.

9. Saving Private Ryan (Steven Spielberg, 1998)

Five years after he created one of the definitive films about the Holocaust with Schindler’s List, Steven Spielberg returned to World War II with Saving Private Ryan and delivered what can arguably be called the definitive film on D-Day in the process.

The plot of the film is set in motion when General George Marshall learns that three out of four brothers have died in action and that the fourth brother, Private James Ryan (Matt Damon), has gone missing in action during the invasion of Normandy. As the General is informed that the brother’s mother will have to be notified of the deaths of three of her sons on the same day, he decides that the last remaining brother needs to be found and sent home. Three days after having landed on the beaches of Normandy, Captain John Miller (Tom Hanks) is given orders to assemble a team to go find Private Ryan.

Joining him are his right-hand man Sargeant Horvath (Tom Sizemore), a translator (Jeremy Davis), a medic (Giovanni Ribisi), a sharpshooter (Barry Pepper) and three more privates (Vin Diesel, Edward Burns and Adam Goldberg).

As the men make their way into war-torn territory and lives are lost, some of them start having doubts about the sanity of sending in more men to save the life of a single soldier but they ultimately pursue their mission anyway. Once they finally locate Ryan, it turns out that he is defending a bridge of strategic importance and the remaining soldiers in Miller’s team join the battle against the Germans who have the Americans heavily outnumbered.

Featuring one of the most intense battle scenes ever committed to celluloid, Saving Private Ryan starts of with a 24 minute visual assault depicting the landing of the Allied forces on the beaches of Normandy. Rarely has a film depicted such relentless violence in such a convincing realistic manner, perfectly capturing the insanity of war and the total chaos of the landing at Omaha beach from the point of view of the men who stormed the beach.

Whilst the final battle scene in the town of Ramelle is no snooze either, it is this opening madness that stays with the viewer long after the movie has ended. The film was a critical and financial success and received a plethora of award nominations and wins throughout the world. The film was also nominated for eleven Oscars, winning five of them, including a second Best Director statue for Steven Spielberg (the first one being for Schindler’s List).

8. La Grande Illusion (Jean Renoir, 1937)

One of the best war movies (or like all great war movies, an anti-war movie) ever made, La Grande Illusion is a humanistic masterpiece of poetic realism.

The story deals with two French men, one an aristocrat called de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay), the other a working class man called Maréchal (Jean Gabin), whose plane is shot down by German aristocratic aviator von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim) during World War I.

They survive and are invited for lunch by von Rauffenstein, who discovers he shares mutual acquaintances with the French aristocrat; a clear sign that these men might have more in common than they differ from each other. Both men are then transported to a POW camp where amongst others, they meet a French Jew called Rosenthal who generously shares his food rations with others.

They make various plans to escape but just before they finish an escape tunnel, everybody is transported to another camp. The men are moved to a few different camps and finally end up at Wintersborn; a mountain fortress prison commanded by Von Rauffenstein.

During their time of incarceration, the two aristocrats from different nations almost become friends until Boeldieu acts as a distraction in order to let his fellow prisoners escape, and von Rauffenstein is forced to shoot him. He regrets this greatly and as he nurses de Boeldieu during his last hours, the men mourn the disappearance of their class, which the war will clearly bring about. Meanwhile, Maréchal and Rosenthal travel across Germany trying to reach safety until they finally reach Switzerland.

The title of the film was taken from the book The Great Illusion by economist Norman Angell, who argued that war was futile because of the common economic interests of all European nations. The film examines the absurdity of war, the decline of aristocracy across Europe and the bond of humanity which we all share. It has been said that Renoir specifically created the character of the Jewish Rosenthal as a symbol of humanity across class lines and to also counter the rise of anti-Semitism in Hitler’s Germany.

La Grande Illusion received a “Best Artistic Ensemble” prize at the 1937 Venice Film Festival despite being banned in Italy and Germany. However, the greatest acknowledgement of its potent message was that Joseph Goebbels declared the movie: “Cinematic Public Enemy No. 1” and ordered all prints to be destroyed. One of the greatest films ever made and an absolute must-see for all lovers of cinema.