7. Rome, Open City (Roma città aperta) (Roberto Rossellini, 1945)

The first and arguably best film in Roberto Rossellini’s War/Neorealist Trilogy, Rome, Open City is a landmark film. Not only is it possibly the quintessential film of the Italian neorealism movement, which in one way or another influenced virtually everything that came after in the history of cinema, it also opened the doors to Italian and European films in the United States, where it received unanimous high praise.

The film follows the lives of various inhabitants of Rome, many involved in the resistance, during the Nazi occupation, who have declared the capital an “open city”, meaning that people can more or less move about freely without fear of being bombed by the Allies as the Germans are preparing to leave Rome behind.

But during this time the Nazis are still vigorously hunting down resistance fighters and the movie starts as we follow Italian communist and Resistance fighter Giorgio escape a German raid and take refuge in the apartment of Pina (Anna Magnani) and Francesco, who are both also involved in the Resistance. Helping them is Don Pietro, a priest sympathetic to the Resistance, who along with the others will pay dearly for opposing the Nazis during these last days of the occupation of Rome.

Rome, Open City is a film that was born out of necessity. Rossellini started working on the script whilst the city was still occupied and started shooting a mere six months after the city was liberated and still in ruins. Due to lacks of means, the film was shot on low-grade stock without sound and on location with a cast of primarily non-professional actors.

Turning all these disadvantages around, Rossellini created a work of unparalleled realism and authenticity and kick-started the Italian neorealist movement, which would deal with the difficult conditions after the war and remain popular well into the fifties.

6. Battle for Algiers (La Battaglia di Algeri) (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966)

An Italian-Algerian co-production, The Battle of Algiers depicts events from the Algerian War for independence and clearly owes much of its realistic docudrama style to Italian neorealism.

The film is primarily told through the flashbacks of Ali la Pointe as he is captured by the French. Once a thief who was recruited by the National Liberation Front when in prison three years earlier, he joined the guerrillas as they regroup and organize into revolutionary cells in the Casbah to drive out the French occupiers and has since risen amongst their ranks.

The guerrilla and terrorist tactics that the Front employs result in escalating violence from both sides with the French ultimately gaining the upper hand, winning the Battle of Algiers and executing Ali. But the film ends with an epilogue in which nationwide demonstrations and riots show that even though they won Algiers, the battle for the country had already been lost by the French.

A stark re-creation of the period and events, often filmed with handheld cameras and employing both professional and non professional actors, the majority of which were Algerian, The Battle of Algiers was partly funded by the Algerian government and it’s clear where director Pontecorvo’s sympathies lay.

The film had such a realistic look to it that American copies carried a disclaimer stating that no actual newsreel footage was used during the making of it. The film won the Golden Lion as well as the FIPRESCI and City of Venice Prize at the Venice Film Festival and was nominated for Best Foreign Feature at the Oscars. Due to the politically sensitive content of the film, the movie was banned in France for five years.

5. Army of Shadows (L’Armée des Ombres) (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1969)

Adapted from the book of the same name by Joseph Kessel, Army of Shadows is a 1969 French film about the French Resistance directed by Jean-Pierre Melville.

The film follows various members of the French Resistance and centres around Philippe Gerbier (Lino Ventura), the head of the Marseille Resistance network. The film starts when Philippe escapes whilst being transported by the Gestapo. He makes his way back to Marseille where he meets up with his men and they proceed to kill one of their own members who had betrayed him.

When some of the the members of his Resistance cell are captured, Gerbier and some of his associates try to rescue them from prison but the attempt fails and he finds himself a wanted man as his photo is now circulated everywhere by the Gestapo. He gets caught again but also manages to escape again but one of his associates, Mathilde (Simone Signoret), is arrested and made to talk by the Gestapo.

Arguably Melville’s greatest film, Army of Shadows is a grim and unromantic depiction of the struggles of the French Resistance. Don’t expect large scale battles, action scenes or displays of overt heroics from this film. Army of Shadows is an understated film which deals the effects on the individuals fighting an underground war where covert actions and isolation are of the utmost importance.

Lino Ventura gives one of the best performances of his career and is supported by a great cast, which also includes Paul Crauchet, Christian Barbier, Jean-Pierre Cassel and Paul Meurisse. The film wasn’t well received upon its initial release, didn’t do a lot of business and wasn’t even released in the United States for nearly 40 years but has since become one of Melville’s most celebrated works and is now considered as one of the best films about the second World War ever made.

4. Full Metal Jacket (Stanley Kubrick, 1987)

Based on the novel The Short-Timers by Gustav Hasford, Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket was overshadowed by Oliver Stone’s Platoon, which was released six months earlier and had won various Oscars including Best Picture, but ultimately proved to be the better Vietnam War film and another towering achievement by its famed director.

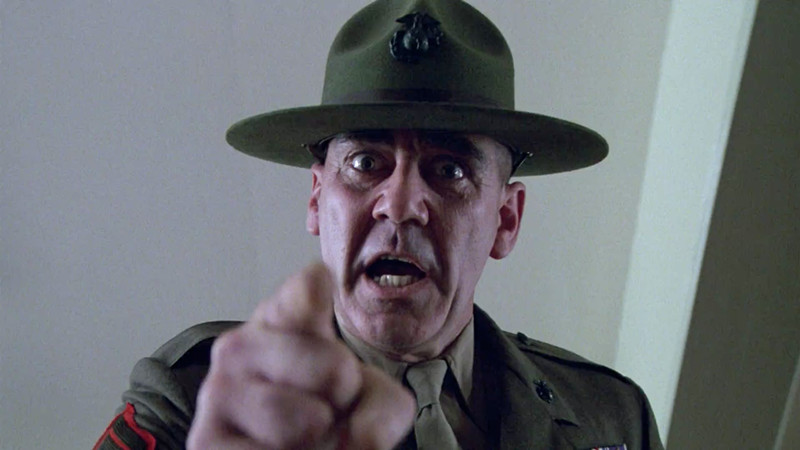

The film is split up in two separate acts which follow a group U.S. Marines as they prepare for war and are sent over to Vietnam. The first act is set as Parris Island boot camp, where the group of new recruits, including private J.T. ‘Joker’ Davis (Matthew Modine), private ‘Cowboy’ (Arliss Howard) and private Leonard ‘Gomer Pyle’ Lawrence (Vincent D’Onofrio), meet their drill instructor Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey) whose extreme drilling tactics start having a heavy toll on the mental well being on private Pyle, especially after he is singled out by Hartman for having a doughnut in his footlocker.

The second act sees the platoon being shipped off to Vietnam with Joker having been assigned the role of war correspondent and teamed up with with Private First Class Rafterman, a combat photographer. The two are sent out to cover the Battle of Huế where Joker meets up with Cowboy, who is now a Sergeant. The film continues to follow the squad through various set pieces, culminating in a lengthy battle with a Vietnamese sniper.

In a year that was stuffed with films about the Vietnam War, Full Metal Jacket stood head and shoulders above the competition and received greatvcritical recognition. The first half of the movie set in the boot camp was specifically lauded as were many of the film’s performances, especially R. Lee Ermey as the tough-as-nails drill instructor and Vincent D’Onofrio as the damaged private Pyle.

Financially the film didn’t fare that well, mainly due to the fact that Platoon had been a massive success in the months leading up to its release. And unlike that movie, Full Metal Jacket was snubbed at the Oscars, where it received only one nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay. It would be a full twelve years before Kubrick released his next and final film, Eyes Wide Shut.

3. The Thin Red Line (Terrence Malick, 1998)

After a hiatus of twenty years director Terrence Malick returned to filmmaking in a big way with The Thin Red Line, an adaptation of the same name novel by James Jones about the Guandalcanal campaign in the Pacific. The book was a follow-up to From Here To Eternity, also written by Jones, featuring some of the same characters but with their names altered.

Private Witt (Jim Caviezel) is a deserter who is living a carefree existence on an island paradise with the natives somewhere in the South Pacific. But when he is found and captured by the Navy, he gets debriefed by Officer Weksh (Sean Penn) and is then redeployed amongst the troops that will be tasked with recapturing the island of Guadalcanal from the Japanese.

From there the film becomes a series of segments, touching upon the experiences of a great variety of soldiers, as the men go ashore the island and try to take it from the Japanese. All the time the viewer is privy to Witt’s innermost thoughts as voice-over narration contemplates life, death and all that is occurring around him.

Not a traditional war movie in the least, The Thin Red Line features very little combat and incredible striking natural beauty, courtesy of cinematographer John Toll, who makes the Pacific surroundings look like paradise, contrasting sharply with the human scenarios which are played out in it. The film also features a fantastic ensemble cast which in addition to the above mentioned actors also includes John Cusack, Nick Nolte, Woody Harrelson, Ben Chaplin, Adrien Brody, John Savage, Jared Leto, John C. Reilly, John Travolta and George Clooney.

Apparently even more actors (including Billy Bob Thornton, Martin Sheen, Gary Oldman, Bill Pullman, Lukas Haas, Jason Patric, Viggo Mortensen, and Mickey Rourke) were included in the original vision of the film but all of them ended up on the editing room floor. Nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Director, the film ended up winning none. The film did however win the Golden Bear for Best Film at the Berlin International Film Festival and announced the glorious return of one of today’s greatest American filmmakers.

2. Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

A film that is as infamous for its troubled production as it is for its epic scale, Apocalypse Now sort of rewrote the book on that a war movie could be with its surreal and hallucinatory imagery and was an immensely ambitious and truly unique film. Loosely adapted from the book Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad, Francis Ford Coppola and John Milius changed the setting from colonial Africa to war-torn Vietnam but stuck to the book’s underlying themes of madness and the duality of man.

The film follows Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) as he is sent deep into the Cambodian jungle to kill a Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), who has gone AWOL and is rumoured to have lost his mind. Willard and his crew, which consists of “Chief” (Albert Hall), Lance (Sam Bottoms), “Chef” (Frederic Forrest) and “Mr. Clean” (Lawrence Fishburne), first meet up with Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall) who clears the river mouth with his troops and escorts them to their River Patrol Boat.

From there, the men start their long journey along the Nung river, deeper into jungle and the madness of war. Along the way, they are attacked by the indigenous people, make a stop at an American camp where a Playboy Bunny show is being staged for the soldiers and finally arrive at Kurtz’s camp. There they meet a manic photographer (Dennis Hopper), who thinks that Kurtz is a genius and find out that the Colonel has been living a god-like and brutal existence amongst the natives.

Despite it’s lengthy and trouble-ridden production process and going way over budget, Apocalypse Now became both a critical and financial hit when it finally appeared in theatres in 1979. The film was first shown at Cannes where, despite it being labelled a “work in progress”, it won the Palme d’Or and went on to receive eight Academy Award nominations upon its release in the United States, ultimately only winning two for Best Cinematography and Best sound.

Both Francis Ford Coppola and Robert Duvall won Golden Globes as well as BAFTA awards for Best Direction and Best Supporting Actor. A landmark in cinema and a perfect representation of the madness of war, Apocalypse Now ranks amongst the best films ever made.

1. Come and See (Elem Klimov, 1985)

One of the most chilling, horrific and haunting war films ever committed to the screen. Director Elem Klimov never made another film after Come and See, stating that he had nothing left to say. With a final film like this, he does not have to.

Set in the Byelorussian Soviet Republic (modern day Belarus), the film follows Flyora, a young villager, who digs up a old Russian rifle and proceeds to join the Partisans (local resistance). Soon separated from the main force, Flyora goes on a journey through the country where he eventually witnesses the true horrors of war.

The film is not outright violent, infact hardly any violence occurs on screen. Rather there are simply glimpses of violence. The brief shot of the bodies in Flyora’s village will shock you right to the core but the true horror comes in the final scenes where he witness the real evils of war as the SS burn down a hut filled with civilians, laughter and joy spread across their faces as they drag a young girl off to be raped.

In the end, the horror is not conveyed through violence or blood or gore, rather it is through the eyes. The film’s most memorable shot (seen on the poster) is when Flyora is posing with three Germans, one of whom is pointing a Luger at his head for a photo, a look of sheer horror and torment in the eyes that makes you wonder how much of it is acting and how much is real. This is a film that will stay with you for a long time.

Author Bio: Emilio has been a movie buff for as long as he can remember and holds a Masters Degree in Cinema Studies from the University of Amsterdam. Critical and eclectic in taste, he has been described to “love film but hate all movies”. For daily suggestions on what to watch, check out his Just Good Movies Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/goodmoviesuggestions.