6. Being John Malkovich – Spike Jonze (1999)

Along with Memento, Fight Club, Mullholland Drive and American Psycho, Being John Malkovich came along at very singular time in American cinema. It was a moment when reality felt unstable, truth was easier to question than to merely accept and cinema was a useful pry bar against the limits of mundane perception. The loose and easy way director Spike Jonze and writer Charlie Kaufman slough off normality for the vibrant surrealism of this film’s universe has no parallel in current cinema.

Theirs is a universe that operates by approximately the same rules as ours. Day to day life requires a job, relationships are hard, New York City is a cold difficult place to be, and John Malkovich is a moderately famous actor. But unlike our reality theirs juts out into strangeness consistently enough that when a character finds a portal into John Malkovich’s head it’s not entirely absurd, just kind of odd.

While it is admittedly weird that anyone could access someone else’s mind and body through a small door in a New York high-rise, we often forget how many surrealities we have encountered and absorbed in recent time. One of the biggest of which is film, the privilege to observe and enjoy remote realities in a consequence free environment is an absurd luxury.

And while Being John Malkovich considers the experience of film going in exaggerated terms, to the extent that we enter a movie star’s private thoughts and experiences, it is possible to consider it mere extrapolation of our own experience. It takes the strangeness we know and accept and pushes at its boundaries, creating an original menu of conditions, assumptions, and perceptions.

7. Certified Copy – Abbas Kiarostami (2010)

What makes art valuable? Is it the aesthetic qualities, a pure sensory stimulation? Or is it the provenance, a sense of proximity with persons of artistic genius, the privilege of communing and connecting with items of beauty that tie us back to persons of genius? Certified Copy seeks to investigate the importance of authenticity and the limits of our ability to spot fakery.

It tells the story of an author who has written a book extolling the virtues of artistic forgeries, suggesting that a copy might be of value despite its inauthenticity. He is approached and invited on a ride around the Italian countryside by a woman who is interested in his topic. They are two single people, stylish and attractive, over forty and possessed of a certain weariness that makes them simultaneously less tolerant of one another but also more patient with the situation.

As they get to know each other, talking at length and delving into one another’s lives, they easily and sharply call the other out when they are inauthentic or wrong. But they stick with their association because one suspects they both know the weight of loneliness and the value of a sharp, engaged, attractive companion.

Much of their talk is concerned with the topic of authenticity and the legitimacy of a convincing copy. Somewhere along the way it stops being just about art. In a café an old woman mistakes them for a married couple. They begin to play the part of a married couple, on vacation trying to rekindle a waning romance. They play their roles easily without discussing the transition. Suddenly they are married and they both explore the dynamic with ease and passion.

Over the last third of the film the two characters slip further and further into this artifice such that the viewing audience must begin to question the nature and value of authenticity, much the same way the characters had been doing previously. The scenes in which they behave like lovers, argue like spouses, and remember things that never happened elicit the same response they would if the plot actually had them as husband and wife. It is a perfectly convincing copy. Which the film its self is also.

Whether or not the characters are actually married in the story, these actors are not. This is all 100% artificial. We are made complicit in the argument about the validity of an imperceptible forgery. Whether original and authentic or not we perceive and enjoy the artifice, which is where the beauty lies.

8. The Conversation – Francis Ford Coppola (1974)

Francis Ford Coppola’s narrow and claustrophobic meditation on truth, perception, and privacy, The Conversation, is about the limits of our control upon how we are perceived and upon what we perceive. The main character is Harry Caul, played by Gene Hackman. He is a surveillance specialist who is pathologically controlling and controlled.

He barely speaks to anyone; he keeps no items of personal importance in his home. He has no home phone as the movie opens and has four locks and an alarm system wired to his apartment door. He is an expert at making sound recordings of others but he sternly refuses to give anything of himself away to the outside world.

Harry Caul stands in stark contrast to the protagonists in Blow Up and Blow Out. All three films hinge on a mysterious recording of a possibly sinister event. For Harry Caul the item is a recording he was hired to make of two lovers in a park, apparently making plans to meet and tryst more privately.

Unlike the men at the center of Blow Up and Blow Out though, Harry is not interested in the contents of what he records. His ear is trained to analyze the technical aspects of recordings but his mind is not honed to analyze the content. He is not a curious person, as he angrily tells his subordinate played by John Cazale who annoys him by constantly asking open ended questions about the couple, trying to get Harry to speculate.

Slowly though Harry becomes worried about the couple in his recording. He hears one of them saying, “He’d kill us if he got the chance.” He suddenly suspects their lives are in danger. This takes him back to an old case he had worked on wherein his recordings led to the gruesome deaths of a family. We learn he was traumatized by this and it drives him to do what he has always resisted doing, he gets involved in the case he was hired to record for.

What Harry encounters and what we seem meant to take away from The Conversation is that however sophisticated the techniques and technology of recording become, it is the ambiguity of content, the holes in our perception, which can be our undoing.

9. Mulholland Drive – David Lynch (2001)

David Lynch’s Mullholland Drive is a film composed of overlapping cinematic realities. It takes place in a Hollywood fabricated from the material of movies: the tropes, types, and plot lines we all know. It’s a reality in which that material coexists with its self in multiple narrative currents, colliding, interacting, and reacting to one another as we watch.

It tells the story of a woman who is in a car accident. She wanders off with a head injury, amnesia, and a bag full of money. She meets Betty, a small town girl arrived in Hollywood destined to be a star. The mystery woman is your classic femme fatale, buxom and smoldering.

Betty is your classic Hollywood dreamer, innocent yet worldly, preternaturally talented and beautiful in a clean fresh-faced wholesome sort of way. She and the mystery woman, who decides to call herself Rita, taking the name from a poster for the movie Gilda, starring Rita Hayworth, set out to unravel the mystery of “Rita’s” identity and how she came to have all of this money.

Meanwhile a film director is being strong-armed into casting a woman for his movie whom he does not want. He is the archetype of the jaded former Hollywood wunderkind. His life falls apart as mysterious forces manipulate him. His story is a sort of satiric Hollywood takedown, exposing the filthy business of movie making.

These two story threads seem unrelated until in the last thirty minutes, instead of connecting and coming to a mutual conclusion, the two stories intertwine realities. Both story lines partially break down, exchange actors, characters, plot elements, and props. As though someone has put two scripts in a bag and shaken them up together.

The implication seems to be that we are not watching some sealed and consistent creation, something invented and discreet. Instead when we watch a movie we are peeking in upon a separate corridor of reality in which all of these types and tendencies coexist at all times. They combine, entangle, and recombine infinitely and this time instead of seeing a full story result we see one of the collisions when things get shaken up before one or the other can come to a full conclusion.

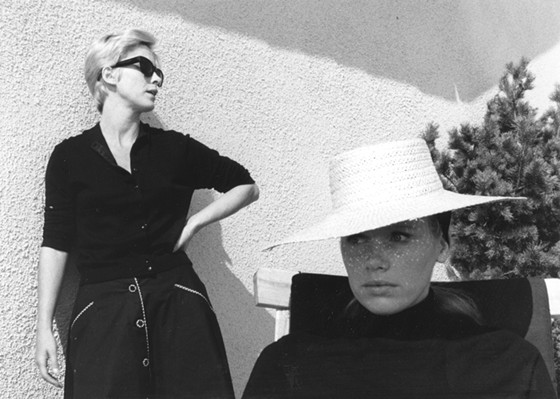

10. Persona – Ingmar Bergman (1966)

Ingmar Bergman always had a reputation for being enigmatic. His slow burning and deeply perceptive comedy/dramas reveled in symbolism and an open relationship with metaphysics and meta-self-awareness. Still his plotlines had always been robust and the story had always remained central.

For 1966’s Persona he scaled back the plot, presenting an absolutely minimal story about two women alone in a seaside cottage, confronting their own senses of being. What takes over in place of a more robust cast and plot is Bergman’s love of enigma and the symbolic. In fact the first few minutes of the film are taken up entirely by seemingly unrelated imagery, beginning with a film projector coming to life. Persona seems to declare from the beginning “This is a Film and as little as possible will get between this film and the elemental philosophical concerns of capitol ‘F’ Film.”

The central philosophical concern, addressed bluntly and continuously throughout the story, is the nature of self and identity, the desire for authenticity and a renunciation of artifice. The main character is an actress who has had a psychological breakdown and now refuses to speak.

The second main character is a young nurse assigned to take care of her. They are sent to a seaside cottage so the actress can convalesce. There the young nurse opens up to the silent woman who listens indulgently. They share moments of stark intimacy but the actress never speaks.

They quarrel when the nurse reads a letter the other woman has written about her, in which she has taken a dismissive tone about the things the other woman has revealed.

The story of their association acts as a catalyst for moments of more cinematic contemplation when the camera and the script of the film take advantage of our blind spots as the audience to suggest these two women are beginning to merge into one. As though the search for authenticity, difficult as it may be in life, when tackled by a medium as elementally false as film, can only crumble into a complete abdication of all definitions and distinctions.

By the end the two women are back where they began and the film returns to the extra-narrative space where it began with the montage of unrelated images and the projector now shutting off. Film appears as a finite series of deceptions, a self-aware mask against authentic perception.

Author Bio: Yorgo Douramacos is a writer, filmmaker, and photographer. He is an American pop culture omnivore and has more opinions than he knows what to do with. He maintains cinema, music, and literature blogs which can be found through his website, http://yorgolee.com