6. In The Mood for Love (2000, Wong Karwai)

Since the early 1990s, Hong Kong auteur Wong Karwai has made a series of visually stunning films that cemented him as one of the most popular Asian filmmakers working today. In The Mood for Love, a period romance film about unrequited love, is probably his most famous and arguably his best to date.

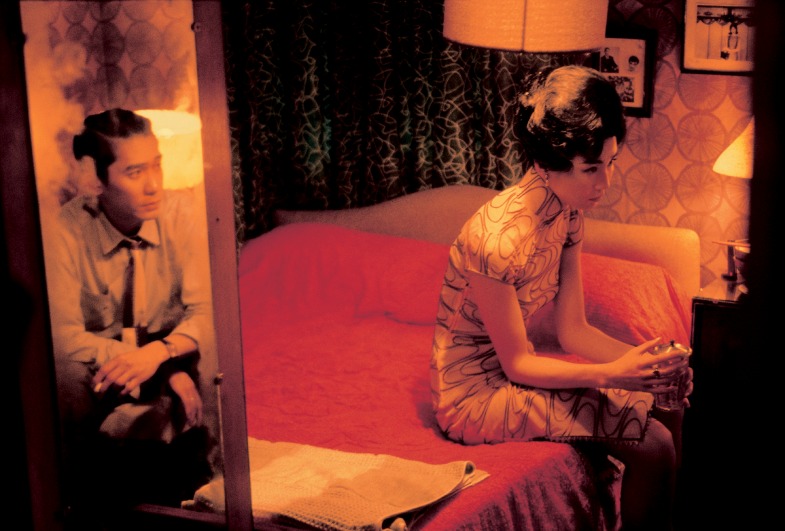

A man and a woman, both married, fall in love but have to let go the romance because of the restrictions of traditional moral values. This is the plot of Spring in a Small Town, one of the best films in China, and it’s basically retold here by Wong. The director removed the social subtext and added his own flavor to it. Cinematographer Christopher Doyle used color red and yellow to emphasize the intimacy between the doomed lovers.

The soundtrack is full of nostalgia, especially the theme song “Huan Yang De Nian Hua”, a popular Chinese song in the 1940s and the inspiration for the Chinese title of the film. The song “Quizás, Quizás, Quizás” offers the perfect tempo as the female protagonist descends the stairs.

Hong Kong super-stars Tony Leuang and Maggie Cheuang both contributed their best performances of their careers and Cheuang’s cheongsam costume in the film made cheongsam a blooming fashion. Undoubtedly, In The Mood for Love would be the perfect entry to his spellbound cinematic world.

7. The World (2004, Jia Zhangke)

How can you travel around the world in just one day? Well, it can be realized in Jia Zhangke’s film The World. Inspired by a journey to a theme park in Beijing full of miniatures of wonders around the world, Jia Zhangke was surprised to see the tourists’ simple satisfaction with the sight of Eiffel to the Egyptian pyramids within one day and decided to make a film depicting those living in this miniature artificial world day after day.

Jia Zhangke is the flag-bearer of the “Sixth Generation” of Chinese directors. His films examine the lives of ordinary Chinese people during the country’s rapid development in the last few decades. In The World, the director tries to reveal the dangerous, seductive and confusing side of globalization.

People get lost in a cage built by themselves, they live in an illusion that the world is getting smaller while not realizing the unbridgeable distance between different lifestyles, cultures and people. Workers in the small miniature world park are suffering from different miseries, though repeating the same chores every day.

Jia started making films in his hometown, then he made films in other places of China, The World showed us a bigger vision, a world view from a true artist. Jia is becoming a stoppable force of World Cinema and The World is an unmissable masterpiece from the filmmaker.

8. Yi Yi (2000, Edward Yang)

Yi Yi, Edward Yang’s family epic, is a Chinese classic with philosophical profundity. The title, also translated as A One and a Two, means the endless circle of life in Taoist sense.

Yang is one of the three most important filmmakers of the New Taiwan Cinema (the other two being Hou Hsiaohsien and Tsai Mingliang). His postmodern cinema is full of social critique and Antonionian visual poetry.

Like Hou and Tsai, Yang is an extraordinary city filmmaker, you can see many shots of the cityscape reflected through the windows, like the opening of Antonioni’s La Notte. In his movies, Yang threw a lot of questions to modern people, questions that had to be answered by both the characters and audiences.

The films offered a perfect formula for future Oriental family dramas. Every member of the family has their own worries; each of them feels lonely and alienated under the same rooftop. No matter how hard you try, life, in essence, is constant suffering. Yang showed us his philosophy of life in Yi Yi, and of course, his pessimism towards life.

Yi Yi is full of rituals, it begins with a wedding and ends with a funeral. The closing line of “I feel I’m old as well” spoken from the mouth of a young boy is the perfect summation of this film journey called life.

9. The Housemaid (1960, Kim Ki-young)

You probably didn’t know the name Kim Ki-young unless you are a die-hard fan of South Korean cinema. While filmmakers like Park Chan-wook, Bong Joon-ho and Kim Jee-woon are more familiar to young movie buffs, Kim Ki-young is like their spiritual godfather and The Housemaid is the film that inspired a whole generation of South Korean directors.

Kim, with other important South Korean directors of that period like Shin Sang-ok and Yi Man-hee, created the first Golden Age of the country’s cinema during the late 1960s and early 1970s, a time when South Korea was the biggest film-producing country in Asia. He made some neo-realism like films before his departure from the style and his first masterpiece The Housemaid.

The film works like a chamber movie, almost all the actions take place in the protagonist’s home. The always moving camera effectively showed the interior of the house, you can see many dolly shots move between the Housemaid’s room and the room with the piano, or shots move up and down stairs. You can always feel the depth of the shots with people in both foreground and background, when they show the close-ups of the housemaid’s face, it’s always the most haunting thing in the movie.

The Housemaid is a melodrama both erotic and psychological. The director never shows anything too explicit concerning the relationship between the man and his housemaid, but the scenes with housemaid seducing the man are extremely erotic. The tension is not only built in an erotic way, it’s also very psychological.

The director uses the rat poison as the Mcguffin and constantly places the camera inside the kitchen closet to show the whereabouts of the poison. Everyone in the movie is either trying to poison someone or preventing oneself being poisoned.

Kim was so fond of the story, he re-made it twice in Fire Woman (1971) and Fire Woman ’82 (1982). His works remained unknown to the Western world until the late 1990s. Unfortunately, the great director passed away before his first-ever retrospective in Berlin in 1998. Thanks to World Cinema Foundation and Criterion Collection, this Asian masterpiece was able to meet wider audiences.

10. Pather Panchali (1955, Satyajit Ray)

Probably the single most important film in Indian cinema history, Satyajit Ray’s feature debut and masterpiece introduced him and Indian cinema to the world cinema stage in the mid-50s. It is the opening chapter of the director’s renowned “The Apu Trilogy”, which is considered one of the greatest trilogies in cinema history.

Satyajit Ray is a giant figure in Indian cinema. He worked in an ad agency as a design artist in his early years, after watching the films of Jean Renoir and those Italian neo-realism films, he decided to make films. Ray is a film auteur in every sense of the word: he looks into every aspect of his filmmaking and has even composed music and designed posters for his own movies. His cinema covers every aspect and period of Indian society. Watching his films is like reading a book about Indian history and culture.

The Apu Trilogy is one of the earliest and greatest coming-of-age tales ever told in cinema. It’s 5 years earlier than Truffaut’s Antoine series, almost a decade earlier than Michael Apted’s Up series, and more than half a century earlier than Richard Linklater’s Boyhood.

There are obvious signs of a cinematic genius in Pather Panchali —the naturalistic and poetic visual style, the humane way to tell a simple story, etc. These traits become trademarks of Ray’s cinema. If you are going to see one Indian film, this is it.