Intro to Film classes aside, the European Art movies of the 1960s and 70s can seem like an aloof, inaccessible area of film history to explore. That much may be true—these movies are not for the feint of heart, embracing deeply existential, spiritual, political themes that completely changed the way movies were made.

Existential dread is to Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman what fast cars and explosions are to Michael Bay, and his iconic film The Seventh Seal (1957) might have the definitive image of all of European Art cinema: a medieval knight plays an actual, literal chess game with death.

Heady subjects are the bread and butter of this film movement, which, while it makes these movies challenging to sit through, also serves as a solemn promise that they offer richer rewards for those that do. Make no mistake, these are the movies that can change your life.

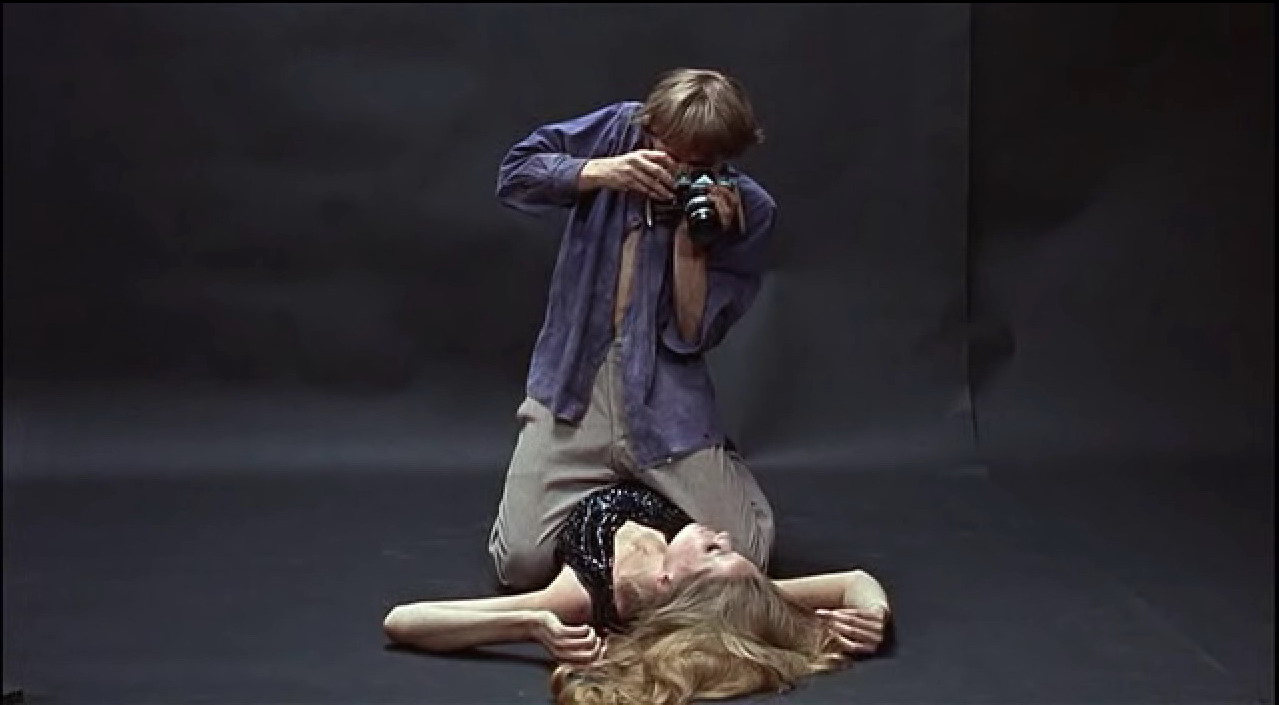

10. Blow Up (1966, Michelangelo Antonioni)

While not Antonioni’s most influential or beloved film, it is surely his most accessible. Blow Up is in english, beautifully photographed by Carlo Di Palma in vibrant colors and bearing something that loosely resembles a plot—something many other movies on this list can’t claim—it’s a film-class mainstay and with good reason.

Few films introduce radical film techniques and concepts like Blow Up while succesfully being both a thriller and a moral question movie, making it a uniquely provocative entry point to heady European movies. (It was famously provocative also for being the first mainstream movie to feature full frontal nudity, something that was headline-grabbing racey at the time.)

The famous plot, which served as the basis for Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation as well as Brian De Palma’s Blow Out, follows a frustrated but oversexed fashion photographer facing a crippling ethical dilemma.

After taking a break from shooting gorgeous models in tantalizing clothing (that leaves little to the imagination), he journeys to a local park with his camear to unwind. Photographing whatever’s around him, he takes a shot of what appears to be a romantic couple. Only, after developing the film, it appears he accidentally photographed a murder, seeing a dead body in the background near the couple.

Stricken with the responsibility of how to proceed, Blow Up plays with the divide between reality, non-reality, and how the apparatus of art might bring both together. The photographer’s camera discovered a truth his senses couldn’t, forging a theme of art telling the truth when humans cannot. Blow Up uses the genre of thriller as a weapon of its own, and its ammunition are weighty ideas fired at the audience with calculated accuracy.

9. Diary of a Country Priest (1951, Robert Bresson)

Backed by a powerhouse performance by Claude Laydu as the titular country priest, this semi-loose adaptation of a book of the same name could make anyone cry. Bresson’s signature style of simple setups, compositions, and editing is unfussy, giving Laydu’s extraordinary acting extra room to embroil you into the film’s deep drama. For a first time performer, his work is all the more incredible.

Diary of a Country Priest might be the definitive film about what it means to have a spiritual life—a classic theme of European Art Cinema. Namely, the film muses on faith. Faith, the film argues, extends beyond the boundaries of religion and into the philosophical soul.

Bresson, an agnostic but with a fascination of religion and ordered spiritual belief, sees faith as a multifaceted idea, one that includes faith in a god, faith in moral values, or perhaps merely faith in yourself. This is material that could have given way to loud pontificating about the divine, but Bresson’s soft touch does anything but.

This is a small story about big things, centered on a lonely, sickly priest who’s ostracized by his mean and unbelieving parishioners. So is the conflict faced every single day: what’s the correct balance between positively influencing other people’s choices in a positive way, and allowing them to make their own mistakes? Bresson doesn’t dare force an answer upon us, instead asking us to ask ourselves.

As a masterpiece, Diary of a Country Priest questions faith and spirituality with such observed grace, contemplating your own spiritual life isn’t just a possibility after watching it, it is a fact.

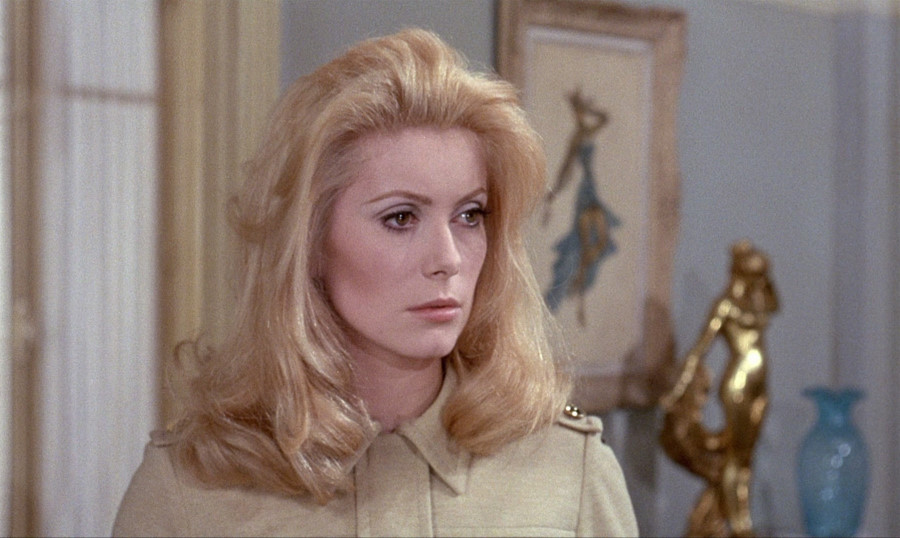

8. Belle de Jour (1967, Luis Buñuel)

In the same way David Lynch fans look back from his revered Mulholland Drive (2001) to Ingmar Bergman’s seminal psychosexual drama Persona (1966) as a call to its unhidden influence, cinephiles should likewise rewind from Stanley Kubrick’s controversial Eyes Wide Shut (1999) to Belle de Jour, a film correctly labeled the most erotic film ever made.

Always concerned with class, Buñuel begins capturing a bourgeoise’ carriage rattling down a dirt road with a glorious mansion in the background. On it are a classical handsome man and a woman whose beauty is supercharged with sex. After the two squabble, the man orders the carriage hands to drag and whip the woman, with her crying out in a state of pain.

One of the carriage hands approaches and gropes her, but instead of pain and defense, she’s in a state of soft core euphoria. Then she wakes up. Reality and non-reality become combatting characters in their own right, and more than one scene is ambiguous about if it’s real life or a dream.

These dream sequences, which are actually sex fantasies imagined by restless housewife Séverine Serizy (Catherine Denueve), are frequent. For her, they are a required escapism, a reaction to her dull life that demands arousal her middle class life can’t offer. So on afternoons when her husband is at work, Séverine starts to prostitute herself. In possibly the film’s most famous scene, an exotic customer has a mysterious box that buzzes when opened.

After seeing what’s inside the prostitute assigned to him leaves, but Séverine immediately submits herself to the request. We never find out what’s in it. In the same way we’re entranced into imagining what’s in the client’s box (Buñuel himself claimed to not even know), Belle de Jour is a two hour treatsie on how the power of sex isn’t in the physical exchange of thrusts and fluids, but in what is imagined. An essential film.

7. Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972, Werner Herzog)

Largely wordless and using visual storytelling to communicate not just the plot but the complex psychological states of the characters, as well as disturbing thematic content, Aguirre the Wrath of God is a landmark of film style.

Aguirre follows a group of Spanish Catholics circa 1960 in search for the fictitious city of El Dorado, the lost city of gold. Dreams that can’t come true are a staple theme of Herzog, as is a brutal reexamination of religion, government, and social order, and despite the brief running time of 94 minutes, each are confronted with far more depth than many longer movies.

Without Aguirre, Francis Ford Coppola’s masterwork Apocalypse Now (1975) might not exist. At best, not in its current form. They share a similar plot: they’re both road (well, technically river) movies from hell (both are inspired by Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness), following a boat based journey through a fever dream jungle. By the end, the characters are insane.

Symbolism of the unknown is thick and earned, as is a pervading sense of man’s uneasy place in the natural world. One set piece hammers the point home: rafts are fighting to stay afloat in dangerous rapids, barely holding together. That Herzog filmed it all for real isn’t just visually astonishing, it’s as crazy as the explorers are by the film’s end. We’re not the rulers of it that we think we are, Herzog grimly tells us.

At times the dreamlike tone and visuals make Aguirre closer to an audio video poem than a film, a feeling that’s so specific that whenever we feel it again it’s identified as Herzogian. The impressionistic style of Terrance Malick owes a severe debt to Herzog, for instance.

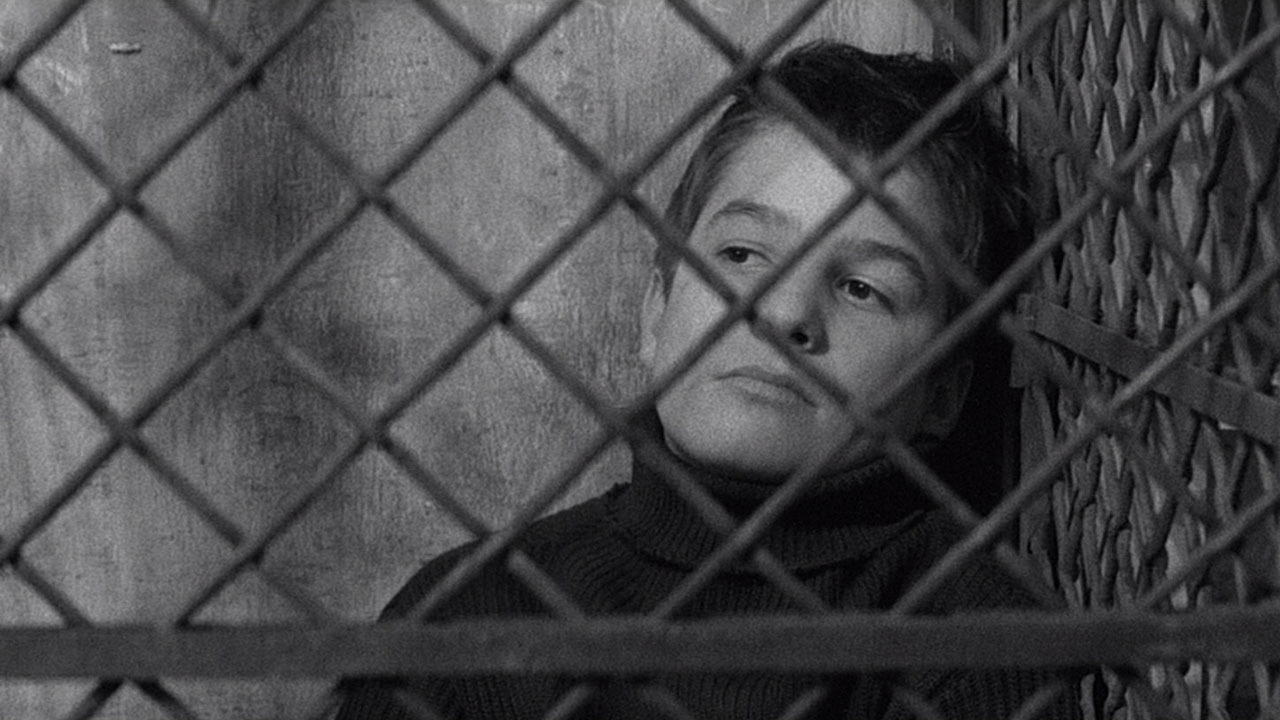

6. The 400 Blows (1959, François Truffaut)

Considered by some to be the radical start the French New Wave, in many ways The 400 Blows is the exception that proves the rule. This movie shares decisively little with the rebellious anti-formalism of contemporary Jean-Luc Godard or psychoanalyst filmmaker Éric Rohmer. Instead, it has a soul.

Unlike his contemporaries who also turned from writing for prestigious film journal Cahiers du Cinéma into game-changing filmmakers, Truffaut’s movies were singularly warm. Many feel Godard’s films lack blood in their veins, instead obsessing over changing film form and pontificating long-winded political statements. For as lauded and amazing his films often were, his cinema was a cognitive one; Truffaut’s was one with heart.

Truffaut shook the status quo not to change the game for its own sake, but always in service of his characters and the story surrounding them. There’s an accessible sincerity to his work that likely stemmed from how it was often autobiographical; The 400 Blows tells a story very similar to that of Truffaut’s own childhood.

This affecting film follows a young boy (an historic Jean-Pierre Léaud) who, after being ignored by his parents and teacher, begins a life of petty crime. The ending—which won’t be revealed here—freezes you in place with its emotional power. Truffaut’s first film, however, isn’t concerned exclusively with the morose or downtrodden.

As with every child’s life is the thrill of misbehavior, the anger of an adult’s ignorance, and, in one of The 400 Blows’ most respondents visual moments, the bliss of an amusement ride. The camera has two modes: still, or subtle movements that annunciate change. What’s most radical here is the smallness of the story, and seeing life itself, without guns, without twists, without genre, as the most human, important thing of all. Traffaut may be right.