5. Vivre Sa Vie (1962, Jean-Luc Godard)

The beginner’s guide to the somewhat impenetrable filmography of Jean-Luc Godard, Vivre Sa Vie is his most accessible and mild but sacrifices nothing of his auteur gamesmanship that came to define him. Within the context of this list Vivre Sa Vie is a companion piece to Belle de Jour: both follow a prostitute.

A key difference: whereas Belle de Jour is all about sex and fantasy, Vivre Sa Vie is entirely about social realism and the sad realities that accompany it. But the film doesn’t mire in depressive plotting, Vivre Sa Vie is equally about the vibrant life of a young woman in a French city in the 1960s doing her best to live life to the fullest extent that she can—so gives way to the title, translated to a life to live.

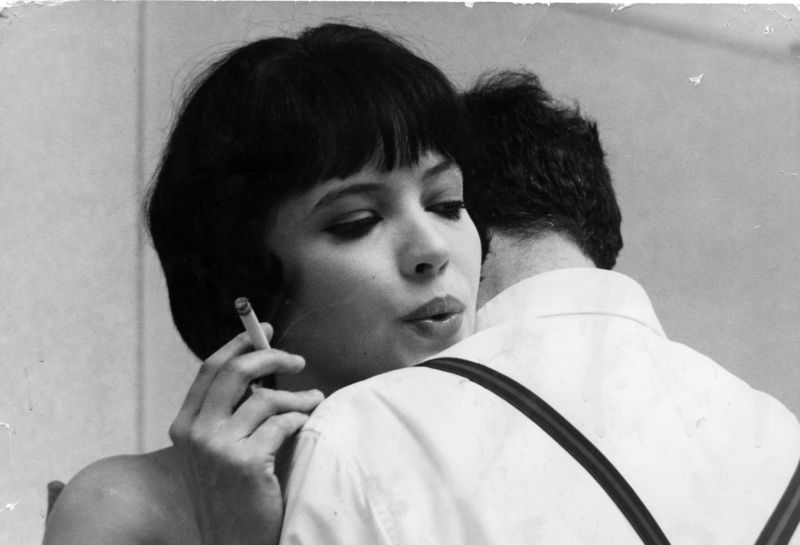

The gorgeous brunette Anna Karina, Godard’s muse, wife, and star of many of his films, communicates both sides of that coin in what might be her best performance. Additionally, if her character seems familiar it’s because it should: with a bob, dancing, and playful attitude, she was the blueprint for Uma Therman’s Mia Wallace character in Pulp Fiction.

But none of this is what makes Vivre Sa Vie, Vire Sa Vie or Godard, Godard. He’s one of cinema’s most beloved auteurs. Here’s why: in a dialogue scene taking place in a Parisian diner cafe, the camera betrays you. The actor’s faces are never seen. Not from the front, and not from profile.

The camera is mischievously placed behind them, forcing the viewer to use their ears instead of their eyes. With their jump-cut editing, idiosyncratic camera placements, and sweeping orchestral scores that suddenly vanish from the sound mix—all of which are featured here—Godard’s movies rethought, reconstructed, and radicalized the very foundation of film form. Filmmakers have been better, and bolder, ever since.

4. Wild Strawberries (1957, Ingmar Bergman)

Bergman at his most sentimental couldn’t be a finer entry point to his long but lavish filmography. Swedish existential cinema, which mostly has to do with sad Swedes contemplating their lonely place in the universe, or before god, or before a god that doesn’t exist, or the moral abandon of society, or contemplating their own death, or, in the case of Bergman’s own The Seventh Seal (1957), a chess game with death, should come with a warning label for sullen, depressive viewing.

What separates Wild Strawberries from his other movies, though, is that it’s funny. It’s also warm, delicate, and positions its main character, Professor Isak Borg, as someone that not only demands empathy, but also kindness. There’s a lightness to Bergman’s touch uncharacteristic of his other films, and it has what might be called a plot.

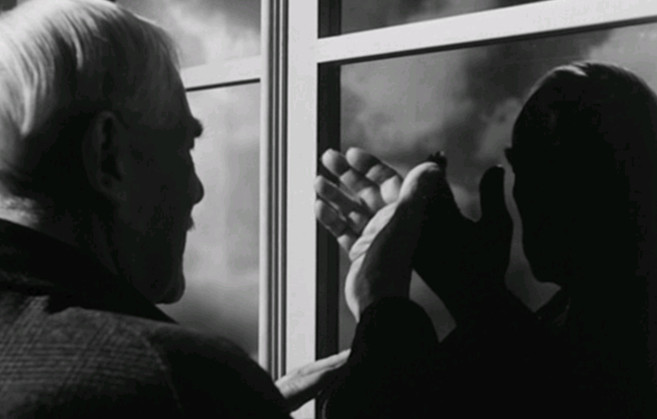

At the end of his life, Borg is set to receive Doctor Jubilaris, an award for his scholarship of 50 years. Wild Strawberries chronicles the long car ride it takes to get there. With a meandering structure that recalls The Odyssey, where passengers are picked up and discarded (with conversations about religion and god in between), and a lead character who regularly slips into daydreams and nightmares, this is the most existential road movie ever made.

Bergman is also seen at his most cunning, and it is those moments of non-reality that reveal why. The story’s simplicity tricks the viewer into a state of ease, one exploited as he slyly transitions into some of the best, most surreal, and most terrifying dream sequences in cinema history. The blurred lines of non-reality and reality becomes a key point of discussion of the film, a debate that in 2015 is still ongoing.

3. Stalker (1979, Andrei Tarkovsky)

Andrei Tarkovsky’s best film, Stalker is a plunge into dystopian cinema unlike you’ve ever seen. In an unnamed year in the future, Russian society is divided into two areas. There’s the industrial, rugged world, a hard world, shot beautifully in monochromatic sepia tone by Alexander Knyazhinsky. And then there’s “The Zone.” What The Zone is, what happened to it (aliens?), or why it was quarantined (radiation?) is never clearly explained—the audience doesn’t know because the characters don’t know.

What is known, however, is a rumor of a room, the room, within The Zone that has the unnatural power to grant people’s wishes. In sharp contrast, The Zone is shot in incredibly vivid color; grass has rarely looked so green, the sound of a trickling stream high in the sound mix is transportive, and nothing seems even a little alien.

That is, until the titular Stalker (frequent Tarkovsky collaborator Alexander Kaidanovsky), an expert guide on entering and exiting The Zone, cautiously maneuvers around the foliage and rocks as if it’s not nature they’re standing on, but a minefield.

All is certainly not what it seems, and it’s never revealed if The Room in The Zone is real, or if it’s all a hoax. Ultimately, it’s a matter of faith. Like all of Tarkovsky’s films, and indeed a persistent through line of European Art Cinema, Stalker is a film musing on faith, and as The Stalker leads a writer (Anatoli Solonitsyn) and professor (Nikolai Grinko) through The Zone and they engage in philosophical discussions respective of their differing disciplines, Stalker works most as a court-room drama.

The accused: society. The spiritual, moral nature of man is scrutinized with deconstructionist rhetoric, examined with a level of sophistication rarely seen in cinema before or since. An absolute masterpiece.

2. Bicycle Thieves (1948, Vittorio De Sica)

The oldest film on this list is probably the most widely seen. Bicycle Thieves, shown in virtually every film class in (at least) the United States, this is one of the most affecting movies ever made. The plot couldn’t be simpler: a working class father (Lamberto Maggiorani) struggling to support his wife, child and baby gets a well paying job to putting up advertisements around Rome. All he needs is a bicycle to go from place to place and carry the advertisements with him.

An early scene of him riding his bike through a gorgeously photographed Rome, fixed with passing cars, trolleys, and a nimble camera riding alongside him, is nothing less than one of the all time most joyful sequences ever. That is, until his bike is stolen.

He searches. He checks the local markets. He talks to the police. He even violently accuses someone who may or may not be the guy who really stole it. The bike is not found. Much of this is in front of his son Bruno (Enzo Staiola), who tragically, and with increasing increments of disappointment in his role model father, is first party to his father’s downward spiral.

But the father is a victim, and so is the way of Italian Neo-realism: these movies emphasized the dire economic situation in Italy in the 40s and 50s, looking at the poor labor class with unphased realism. These movies shot on location, used non-actors like Lamberto Maggiorani as the father, who was a factory worker before getting the role, and set a standard for telling stories about human beings instead of just characters.

1. 8 ½ ( 1963, Federico Fellini)

Like Wild Strawberries, Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ boasts some of the most impressive, iconic, lasting, and influential dream sequences in film history. The standard was set—there was before 8 ½ and there was after. Playful, winking, but sometimes deadly serious, 8 ½ is a one way ticket into the madhouse of Fellini’s subconscious mind.

There’s a traffic jam and the camera slowly tracks behind a car—done with high contrast photography, with overpowering brightness and extreme darkness—unfolds to the beat of a drum. The camera swiftly surveys the scene laterally. There is no escape. Suddenly, chaos erupts. The car, Fellini’s car, which is also your car, gestates with smoke, and panic erupts. Deep breathing. It is impossible to get out. People are looking at you.

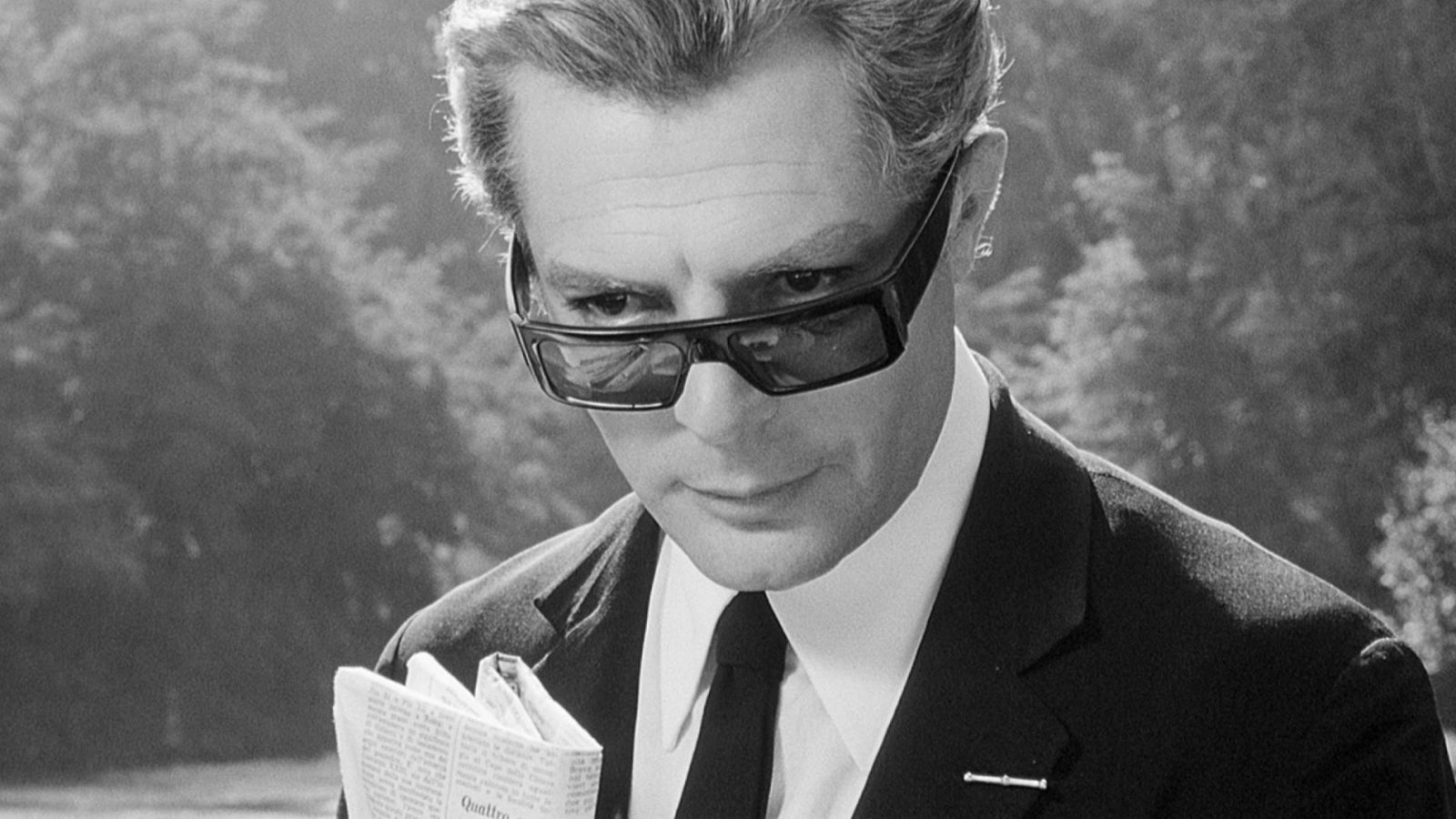

Pairs of arms hang ominously from the windows of a bus. Then, flight. Fellini, who’s embodied by actor Marcello Mastroianni, soars through the clouds. This is only one of the best dream scenes in film history, but 8 ½ has quite a few more. According to some, the entire movie is an elaborate dream sequence, only one with varying levels—a 1960s prophecy of Christopher Nolan’s Inception.

It might not matter. This is a movie about making movies, about a director, Fillini in real life and the sunglasses and black suit wearing Guido Anselmi in the movie, and about creativity. It’s about how life is filtered through a creative process, and what might happen when that creative process hits a blockage, whether that’s a traffic jam or writer’s block. More than anything, though, for all its ponderous self-reflexive expression, 8 ½ is a great time at the movies.