You’re not going to become a cinephile by knowing a little about a lot of movies. Neurologists don’t need to know about astronomy to be scientists. Most of the men and women who earn doctorates and make their livings writing textbooks on Southeast Asian movies would be out of their depth talking about French Poetic Realism, and yet the specialists are among the ultimate cinephiles.

One could safely assume most of them get that way by developing an interest in a specific area, not by acquiring all of the knowledge in every field. This list is for the future specialist. For those making their first big dive into movies, the “official canon” lists of Widely Regarded Masterpieces can be overwhelming to the point of intimidating and off-putting. Sight and Sound, Ebert’s Great Movies, the AFI 100 Movies series, IMDb’s top 250, TheyShootPictures, the Criterion Collection itself…

Most of them, using slightly different formulas and criteria, spit out the same thousand greatest titles that World Cinema has ever produced, leaving you with a lifetime of homework to catch up on. Maybe one day, after countless hours studying other people’s favorites, you too will be able to comfortably toss out sophisticated-sounding titles, like The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie.

You will, like the true sophisticated cinephile, use words like, “Élan” and “Oeuvre,” and find that your use of “embarrassment of cinema” to mean “a lot of movies” was, in fact, correct. Go ahead, be the person who knows just enough about Bergman to be annoying, but not enough to have a personal take. Or, you could find something specific you love and pursue it passionately.

This list is not a best-of, though every movie in it deserves to be on one. It does not expose the reader to even a quarter of the movements, subgenres, or cycles that exist. But they all have a few things in common. They all ooze with passion; none of them sacrifice entertainment in the service of being canon-bait.

They also serve as jumping-off points for different areas, while also maintaining a safe distance from the prom kings and queens of those movements (Seven Samurai will not be featured here). And yet, as a collection, they will let you in the back door to cinephilia. Starting, and eventually ending, with movies that feel familiar, it will venture into foreign, subtitled, black and white, and silent movies.

Most of these movies feel more current than you’d expect, because directors like Tarantino like to, say, homage their favorites. By stealing their stuff. Almost every movie list is really an attempt at saying, “You should watch these movies because…” With that in mind, you should watch these to find a less beaten path that may just end up being a short cut to your future area of passion and expertise. Enjoy!

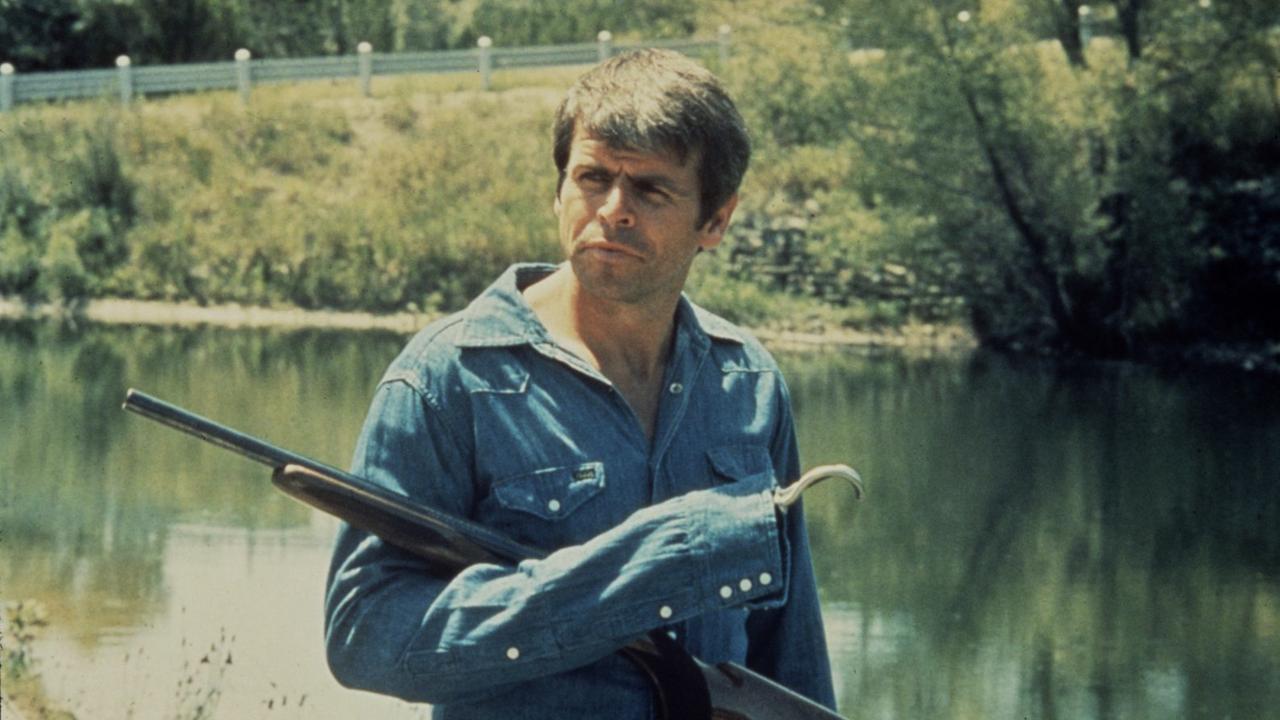

1. Thief (1981, Michael Mann)

That car salesman who lives on your block is actually a diamond thief, and he’s now on the outs with his new employer. Maybe that helps explain why your dad said the dealership was burning to the ground on the way home.

As a member of a family stretching back to somewhat-early Hitchcock and through the French New Wave, Thief offers the new cinephile a chance to jump into three or four dauntingly huge international movements almost accidentally. There could not possibly be a more viscerally entertaining way to study movies.

This is all to say, if you liked Heat, you’re well on your way to learning textbooks’ worth of knowledge about shot composition, building and releasing tension through visual exposition, and the art of the montage. Of course, had Mann not made the most taut thriller this side of Rear Window, then Thief may have been taken seriously enough to make it on all the lists. Not to worry, he did.

It’s necessary to start the journey well inside a comfort zone, and 1981’s Thief is a buffet of 80’s nostalgia, released before the decade was even in full swing. From a historical perspective, Michael Mann continues a lineage of heist pictures established by Hitchcock in the 1940’s, refined by Dassin in the 1950’s, and riffed on by Melville in the 1960’s. Refn would, in turn, respond to Thief in 2011’s Drive. Without a point of reference, though, that may mean very little.

Using narrative realism (the characters think, panic, react, and make decisions like real human beings, even when those thoughts and reactions aren’t the conventional ones) and an 80’s visual flare to the neo noir (fueled by cocaine), the movie stands alone as a scorched-earth paranoia piece, a relatively unseen must-see.

2. The Mission (1999, Johnnie To)

This is the gangster picture Hollywood can no longer make. The gun fu triad movies of Hong Kong instantly establish a connection to Kurosawa, Inagaki, and a slew of other “important” names, but none of that is important yet. After the near death of the Hong Kong studio system in the late 90’s, Johnnie To remains one of the only top tier directors left there.

Gun fu movies are riffs on kung fu movies, with bullets instead of kicks. Kung fu movies evolved as a sect of wuxia (sword play; “wire fu”) movies of the 60’s and 70’s. Wuxia directors studied samurai movies, many from Kurosawa, and tailored them to a Chinese audience. Kurosawa essentially made westerns…

Again, the only thing that matters is that these movies instilled a sense of pace, space, and timing in Johnnie To. And in The Mission, half a century’s worth of distilling the essentials is visible in some of the most refined and brutal action sequences of the last thirty years.

A group of bodyguards ushering their boss out of a mall come under fire. Guns protect him from 360 degrees, locked on the horizon at the top of an escalator, corners, behind trash cans, anywhere the bad guys might come from. These bodyguards stand behind pillars, and guard their man in dead silence for almost too long. Where the hell are the assassins?! The camera grabs them all in an establishing shot, and holds. Nothing.

Then it dollies only only a couple inches back to reveal the assassins, in front of the pillars the entire time, unbeknownst to the bodyguards. To carries on the tradition of Melville and Hitchcock, but splices it into a kung fu movie’s cousin. The Hong Kong New Wave is just about endless. Start at the top, with a movie almost unknown outside of its home.

3. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964, Jacques Demy)

It may be surprising to realize after watching this for the first time that Umbrellas places the viewer smack dab in the middle of a debate between French New Wave auteurs, and their definition of what the New Wave even was. After all, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is a musical about love and war, with a luscious color palette and a plot that seems fairly timeless.

So, Godard said Demy was not a New Wave auteur, Truffaut said he was. Chabrol said, “tastes great,” and Resnais said “less filling.” It’s not necessary to understand the ins and outs of the movement, though, to understand the beauty of this single movie. The audience roots for Character A and hates Character B, and then switches sides. And then again.

It’s a testament to Umbrellas that, in its wake, most musicals try, and fail, to recreate its tactile feel. Its soft whites, rainy blues, jazzy greens, erratic and seemingly improvisational camera. The use of music is kind of profound, when you step back and think about it. Had there been no music at all, it would have worked fine. But, instead of breaking into song occasionally, their life is sung, because their universe exists in music, even when deciding how to handle that nasty pregnancy.

In a way, Jacques Demy makes this non-diagetic music diagetic. It’s in their reality because it comprises their reality. A fan of movies will be a fan of Umbrellas of Cherbourg, with the added benefit of being immediately steeped in the conflicting cultures and ideas of the French New Wave.

4. Seconds (1966, John Frankenheimer)

The few years before Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate helped nudge Hollywood into its new era, the seeds of discomfort with the status quo were sewn by the likes of Sam Fuller, John Cassavetes, and surprisingly, John Frankenheimer in Seconds. Sci-fi, like many other genres, is frequently used as a safe space for social commentary due to its distance from the present time and place.

This is why Seconds, set in the present-day suburbia, is so unsettling. The upper-middle class Leave It to Beaver dad has himself “killed,” and undergoes cosmetic surgery to look like someone else. The company that provides the service sets him up in hippie L.A. as an artist. How would someone handle that, embodying the death of postwar U.S.? How would one adapt to the new world emerging before them?

As a gateway to many experimental movie makers that started popping up around that time, Seconds presents one of the most personal, upsetting fears Hollywood would probably ever allow. It offers no easy answers or tidy endings, which is what makes this thriller so thrilling. The metaphor intertwines and connects with the story so well and so often, it could just as easily be called a microcosm. This is a much more terrifying idea, considering what happens to the main character (Rock Hudson/John Randolph).

Occasionally, you will see those beams of sunlight shine through the constraints of the Hayes Code (which influenced the international studios as well as U.S.). In movies like The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, In A Lonely Place, Pickup on South Street, Seconds (admittedly, the Hayes Code wasn’t exactly still in full force by then), and a comparatively few others, the actors slice through the norms of their era, and glimpses of reality shine through.

It seems way too early, considering the common acting style of the 1960’s, to see a man emotionally break down when taking the first honest look he ever has at his own life. The 1960’s did not show men whimper in shame. John Randolph could teach even Tony Leung something about naturalistic acting. He is only in the movie for the first thirty minutes or so, but almost steals the whole show. From top to bottom, Seconds breathed revolution before the rest of the world even knew one was coming.

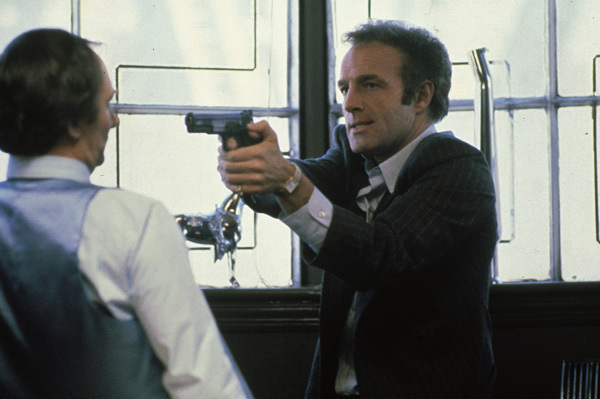

5. Raw Deal (1948, Anthony Mann)

To the noir outsider, the genre may seem like an endless supply of almost identical movies, if only on the surface. Femme Fatales, fedoras, wet streets, cigarettes, the antihero, witty dialog, murder… And this is partly accurate; like the western, one of film noir’s appeal is tailoring the tropes to a movie maker’s worldview.

Coincidentally, Anthony Mann’s worldview in his movies is itself a microcosm, a reflection of the paranoia and anger facing the U.S. during the Red Scare. In Raw Deal, we see all of his trademarks: hands on necks, close-ups of wide, panicked eyes, sweat beads on foreheads, brutal, extended fights, and women are as flawed as the men they decide to associate themselves with, though maybe not as reprehensible.

The movie is a nexus for exploration. Anthony Mann had a magnificent decade-long collaboration with Jimmy Stewart in westerns (which were frequently responses to other westerns from the likes of Boetticher and Ford). Raw Deal is also a gateway into the Poverty Row film noir library, the back door into one of the United States’ great contributions to the world, kindly stolen from German expressionism (Poverty Row were the underdog studios that didn’t have the budgets of MGM and Warner Bros).

An escaped thug is on a collision course with destiny, and the women in his life try to appeal to his emotions to prevent his suicidal mission. He treats his women like garbage and tries to convince them what a good guy he really is. Then we realize he isn’t an antihero at all. Pat, his girlfriend, is the antihero, not because of what she does to others, but because of what she allowed others to do to her so much, and for so long. In the end, everyone’s hell reflects their vice.