It isn’t easy to come up with a list of 12 great philosophical films. Such a list could be based on several criteria. Are these the 12 best films that are philosophical? Is the philosophy in these 12 films the best? Do these 12 films deal with the best philosophical issues? Nay, I say, this list is a combination of the three.

These films deal with tough philosophical issues in a particularly unique and interesting way and, as an added bonus, the philosophy found in them is relatively sound. That said, there are so many to choose from. Which films would you add to this list?

1. Nostalghia (1983)

Russian poet Andrei Gorchakov (Oleg Yankovskiy) is traveling Italy researching the life of a composer alongside his guide and translator Eugenia (Domiziana Giordano). On his journey he meets a lunatic, Domenico (Erland Josephson), who had years earlier imprisoned his family for several years to keep them from the evil modern world.

This appeals to Andrei (and sounds a bit like the plotline of Offret, if you ask me), and he befriends Domenico and tries to help him. Unfortunately, Domenico is a bit beyond help, and so Andrei finds himself struggling to do his work, care for Domenico, and remain in Italy while being nostalgic for his past life in Russia.

As with any Tarkovsky film, Nostalghia is mesmerizing and deep. Nostalghia explores madness and faith, as Tarkovsky wants to do, in a Foucaultian sense, but it’s about something bigger too. Domenico delivers a masterful soliloquy, asking “Where am I when I’m not in reality or in my imagination?” and later “Society must become united again instead of so disjointed. Just look at nature and you’ll see that life is simple. We must go back to where we were to the point where you took the wrong turn.

We must go back to the main foundations of life without dirtying the water. What kind of world is this if a madmen tells you that you must be ashamed of yourselves?” Time has shown that Domenico is eerily correct. I don’t find his solution very appealing, but perhaps Tarkovsky is begging his viewers to find a better way to save the world.

2. Yi Yi (2000)

Yi Yi is a film chronicling a Taipan family told by members of three generations. It begins with a wedding and ends with a funeral, and follows NJ (Nien-Jen Wu), a middle-aged businessman trying to stay upright in a turbulent period of his life.

NJ’s overweight brother is the groom of the wedding and is entangled in all sorts of marital trials, NJ’s wife is away at a Buddhist retreat, his son is in constant trouble at school, his daughter is in the middle of a complicated teenage love triangle, and his mother is comatose. As if this wasn’t enough, he faces problems at work, as he tries to remain honest and stay patient with his colleagues.

It’s unsurprising that such a film is about life and that it analyzes the different things that consume our lives, but Yi Yi is so much more than that. The films greatest philosopher is NJ’s son, Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee), who asks, “Why is the world so different from what we thought it was? Now that you’re awake and see it again… has it changed at all? Now I’ve closed my eyes… the world I see… is so beautiful.” A deeply moving and heartfelt film, Yi Yi is worth the time and pain that it takes to get through it.

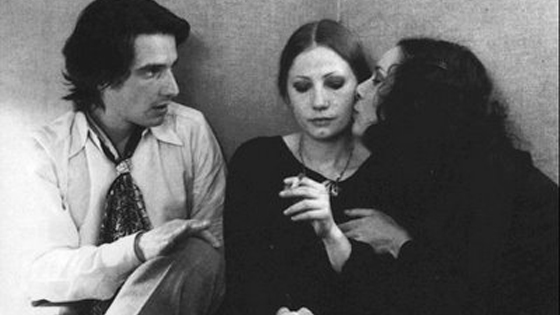

3. The Mother and the Whore (1973)

The Mother and the Whore is a film following Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Leaud) and his lovers in 1972 Paris. Specifically, Alexandre is in a threesome with his girlfriend Marie (Bernadette Lafont), and with a nurse named Veronika (Francoise Lebrun).

Told in a Proust-like way, it examines love, relationships, class and class struggle, honesty, and deceit. Moreover, it’s one of the first films to present love from a non-male perspective, which is to say that Eustache attempted to portray the female side of love (and did a fairly decent job at it, I’m told).

The takeaway from this depiction of French society is that Alexandre is a philandering jerk who uses and abuses women and his place in society, all the while downplaying anything of worth or potential in the film, and that this is okay. Yet, I think in its brutal and bleak dialog, the film also portrays a realist and moralist perspective. As Veronika says “a couple that doesn’t want a baby is no couple.” Sounds pretty orthodox to me.

4. Sideways (2004)

Miles Raymond (Paul Giamatti) is a largely unsuccessful writer and wine connoisseur suffering through the last stages of accepting his divorce. His friend, Jack Cole (Thomas Haden Church), is engaged and will soon be married, and so the two of them decide to drive through the Santa Ynez wine country for a fun road trip of wine tasting together.

If you can’t smell it already, the stench of disaster is written all over this. Jack is a crazy womanizer on the prowl before his wedding, Miles is clinically depressed, and they have plenty of wine at their disposal. Great, just great you guys.

Among many other things, Sideways offers a remarkable analysis of humanity and the science of attraction through witty dialog. It is deeply existential, and chronicles Miles as he sorts out his relationship and tries to find meaning in his life. Big surprise: he can’t find meaning in his job, relationship, or in lots of wine, and the meaninglessness of his existence is too much to bear. Wine offers a short retreat into inauthenticity, but he knows that it isn’t the solution. A great set of the film’s lines bears witness to this fact:

“I’m so insignificant I can’t even kill myself!”

(Jack) “Miles, what the hell is that supposed to mean?”

“Come on, man, you know. Hemingway, Sexton, Plath, Woolf. You can’t kill yourself before you’re even published!”

5. Pi (1998)

Like all Aronofsky films, Pi is a film about obsession. It’s Aronofsky’s first major film, and it follows Maximillian Cohen (Sean Gullette), as he becomes obsessed with finding a missing number.

Max is a genius, capable of predicting stock moves based on the numbers (before there were charts, that is), who spends most of his days computing and fighting migraines. After meeting some Jewish mathematicians, he becomes convinced of a secret code hidden deep in the Torah and tries to find the numerical code corresponding to the lost Hebrew name for God.

At its core though, Pi is about the faith vs reason dichotomy. How much can we know through reason? How much can we know with faith? Can we know truth? Can we know God? Max’s mentor, Sol Robeson (Mark Margolis), takes an earthly and secular approach. As he says when describing looking for codes in the Torah, “this is insanity, Max.” Max’s responds, “Or maybe it’s genius.”

6. Barcelona (1994)

A Whit Stillman masterpiece, Barcelona is about a Chicago Salesman named Ted (Taylor Nichols) working in Barcelona in the 1980s. His cousin Fred (Chris Eigeman) is a naval officer that visits Ted at the beginning of the film because he’s in Spain to manage PR for a naval fleet soon to arrive. Of course, throw in a few relationships, complicated relations between Europe and the US, and Fred’s boisterous attitude, and you have a recipe for disaster.

Yet, the film is about something much more. Stillman’s dialog is masterful and deep. Consider Fred’s questioning:“I’ve read a lot and one thing that keeps cropping up is this thing about ‘subtext.’ Songs, novels, plays—they all have a subtext, which I take to mean a hidden message or import of some kind.

So subtext we know. But what do you call the meaning, or message, that’s right there on the surface, completely open and obvious….what do you call what’s above the subtext?” Stillman’s point here is that we often miss the real significance and meaning of things in life, both in the trivial day-to-day of our jobs and relationships, and in the analysis we do of the things in our lives. Perhaps he’s right.