8. Upstream Color (2013)

The follow up film to the puzzling time travel movie Primer (2004), which won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance on a budget of $7,000, Shane Carruth’s second film is completely different than his debut in terms of narrative and tone. In many ways Upstream Color is even more difficult to grasp.

The premise revolves around a mysterious parasite that is unknowingly ingested by the two main characters (Amy Seimetz and Carruth) and eventually brings them together. The parasite also eventually links them to farm pigs, wild orchids, and Thoreau’s “Walden”. Any further explanation of the plot is useless because the story is only used as a framework to explore philosophical concepts such as loss of identity and breaking life cycles.

A former software engineer with a degree in mathematics, Carruth has evolved into the quintessential do-it-yourself filmmaker working today. He is a writer, director, actor, producer, editor, and composer. The fact that he is involved in literally every aspect of putting his films together allows him a freedom to construct his vision all the way through down to the poster designs and even film distribution.

Even with a budget less than one percent of most movies being made today, he is able to make films that challenge the conventional style of film narrative. Upstream Color works best if the viewer does not try to figure out how everything fits together and just lets the mystifying nature of the film wash over like a hazy blue mist.

7. Amores Perros (2000)

Alejandro González Iñárritu is now a well-known name in film circles after the brilliantly original Birdman (2014) and his darker films 21 Grams (2003) and Babel (2006), which all feature big name American movie stars and garnered multiple Academy Award Nominations.

These last two were preceded by Iñárritu’s first film Amores Perros, which was his debut film and the first of his “Trilogy of Death”. Its use of fragmented narrative has also been referred to as the “Mexican Pulp Fiction” but simply referring to it as another version of Tarantino’s landmark film does not do it justice. The film contains deep themes relating to class, loyalty and the evil that exists in human nature.

The title translates in English to “Love’s a Bitch”, a play on the idiomatic phrase and the characters’ relationships with dogs throughout the movie. The plot is broken up into three separate narratives, each getting its own title card about the characters involved. Each character has a unique relationship with dogs and each eventually falls into tragic circumstances.

The film is disturbing; refusing to censor itself from real life cruelty and animal lovers will be forced to look away during some scenes. Those who can stomach the graphic nature of the dog fighting and gritty realism of impoverished Mexico that Iñárritu puts on the screen, will feel this film in their bones and see it as more than just a clever use of non-linear narrative.

6. The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001)

The Coen brothers’ black-and-white period piece centers around Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton), a small town barber in 1949 California. The film features the typical black humor aspects of the Coen’s films but eliminates the over-the-top characters that usually carry their films. Thornton plays Crane as passive and mundane as possible, hence the title, but still makes the character and his story compelling.

Some have noted the film’s similarities to French writer Albert Camus’ absurd masterpiece The Stranger: both involve unemotional protagonists who get caught up in a murder. The Coen’s have stated in interviews that the idea for the movie originated from a poster they saw that showed the various haircuts from the time period, but there are too many coincidences to not assume that Camus’ philosophical work did not also have a major influence.

Originally shot in color then transferred to black-and-white, DP Roger Deakins displays why he is a master of cinematography. Using simple framing and noir-type lighting, the contrasting shadows and light is a perfect addition to the vague nature of the story. It is not an easy task to create a stimulating film with a main character as boring as Ed Crane but then again,

The Coen brothers are not like most filmmakers. This seemingly simple story is really a brilliant depiction of an emotionally detached man who personifies the existential nature of the 21st century adult male.

5. The Fountain (2006)

Darren Aronofsky was on top of the independent film world in the early 2000’s. After coming off the success of his disturbing, psychological films Pi (1997) and Requiem for a Dream (2000), Aronofosky decided to take his third movie in a new direction. The film was his first time working with a large budget and Aronofsky decided to take advantage of studio money and make his most ambitious film to date.

Aronofksy has referred to The Fountain as a “Rubik’s Cube” of a film. The narrative jumps from back and forth between three stories, all from vastly different time periods. No clear exposition is given to how the stories connect to one another but with close attention to details and careful analysis, according to the filmmaker, it all makes sense.

After receiving large criticism for his third feature, which was both a box-office and critical failure, Aronofsky went on to make two of the best movies of the past few years with The Wrestler (2008) and Black Swan (2010). Although some still consider The Fountain incoherent and by far the worst in Aronofsky’s filmography, it has also developed into a modern cult film after that many people now consider the best work of his career.

4. Syndromes and a Century (2006)

Syndromes and a Century is a Thai film written and directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul originally based on the filmmaker’s parents. The story is broken up in two parts, both have the same characters and similar dialogue, but they are set in different hospitals and have different conclusions to their stories.

The film was controversial in Weerasethakul’s home country of Thailand after he refused to cut scenes that the Board of Censors deemed inappropriate. After first withdrawing it from domestic release, the director agreed to show the film with a black screen in place of the scenes in question.

Even though Weerasethakul decided to fictionalize the story rather than tell an autobiographical tale of his parents, it is clear the film is still very personal and important to the director. There is no strict plot and no dramatic twists, but rather the film becomes an intimate character portrait of two lovers looking back on their relationship.

Similar to the style of American filmmaker Terrence Malick, with static long shots and unhurried pace, Weerasethakul lets the tale of these two people wash over the audience rather than trying to reach out and grab them.

The director has stated the movie is less about love and more about memory and how people transform over time. It’s a shame Weerasethakul has to fight to get the original version of his film shown is his own country because the film is a carefully crafted character study that demonstrates why he should be considered among the top directors in world cinema.

3. Mulholland Dr. (2001)

David Lynch is one of those directors whose style of filmmaking is so original and distinct that his last name has become an adverb. Author David Foster Wallace defined the term “Lynchian” as “a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter.”

In other words, when watching a David Lynch film, there is always a more abstract meaning beneath the surface of what is on the screen. This concept is pushed to its limits in the dark, surreal Mulholland Drive.

The idea for the story was originally developed as an open-ended pilot of a television series but it was rejected by studio executives. While most artists would choose to abandon the project after rejection, Lynch decided to write an ending and make the story into a feature film. It combines the beautiful mysterious nature of Hollywood with the typical Lynchian dream logic that will leave most audience members scratching their heads after the first viewing.

There is no clear explanation given in the film’s conclusion about what is real and what is a dream, instead the ending is purposefully left open for interpretation. The blurred finale which will aggravate some people, but it’s perfect for those who enjoy revisiting a film and looking for new clues that explain its meaning.

2. The Master (2012)

It seems as though PTA is determined to make films that dare audiences to like them. From the sprawling 188 minute, emotional melodrama Magnolia (1999) to the 90-minute abstract, romantic comedy Punch, Drunk, Love (2002); Anderson continues to surprise filmgoers with his unpredictable style of filmmaking. Following his most widely praised film There Will Be Blood (2007), Anderson released one of his most challenging films The Master.

Some critics immediately hailed it as a masterpiece, citing the performances from Phoenix, Hoffman, and Adams (all received Oscar nominations), the jarring score from Radiohead’s Johnny Greenwood, and the beautiful 70 mm cinematography.

Although it unquestionably another technically brilliant film from PTA, many people thought the film’s story was meandering, bland, and pointless. Not to mention the controversial aspect that went with story parallels between the film and Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard.

Allegedly, PTA privately screened the movie for actor and outspoken Scientologist Tom Cruise, who Anderson worked with on Magnolia, and Cruise had many issues with the film. Even without this distraction, The Master is not for everyone. Plot and pacing is thrown away in favor of focusing on the psychology of the characters and intense performances from the actors.

When broken down to its simplest idea, the film is a love story between the lost Navy veteran Freddie Quell (Phoenix) and Lancaster Dodd (Hoffman), the charismatic leader with a cult-like following. The two men are on opposites ends of the male psyche: the instinctual, animalistic nature versus the rational, intellectual mind. Both men seek in themselves what the other brings and this mutual search manifests itself in their strangely endearing relationship.

1. Synecdoche, New York (2008)

Charlie Kaufman is one of the most influential screenwriters of the past 20 years. All the major Hollywood production companies passed on the first script he tried to sell, until director Francis Ford Coppola showed it to his then son-in-law Spike Jonze. Together Kaufman and Jonze created the wildly original Being John Malkovich (1999), which became an unexpected hit and garnered three Oscar nominations including Best Director for Jonze and Best Original Screenplay for Kaufman.

Since his big break into the industry, Kaufman has been turning out brilliant and inventive screenplays including Adaptation (2002) and Eternal Sunshine on the Spotless Mind (2004), for which Kaufman won an Academy Award for screenwriting. With his reputation as a writer firmly established, Kaufman decided to try directing for the first time in his career. What came from this decision was his most personal and misunderstood film to date: Synecdoche, New York.

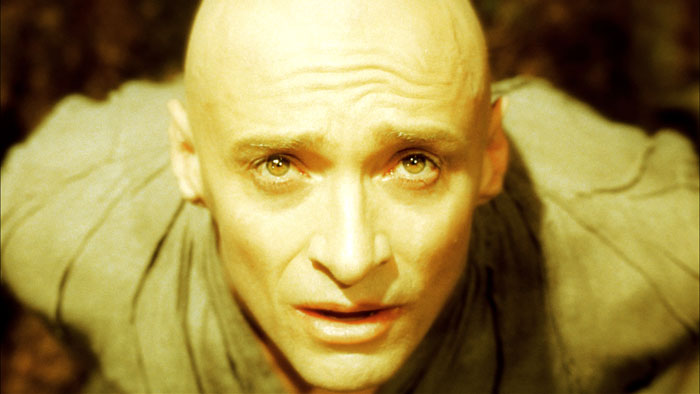

The plot follows Philip Seymour Hoffman as a theatre director on a journey to create an elaborate stage production, and eventually the story starts to blur the boundaries between fiction and reality. Although four critics in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll ranked it among the 10 greatest films of all time and Roger Ebert named in the best film of the decade, the film failed to make even a quarter of its money back at the box office and received zero Oscar nominations.

Every detail down to the film’s title has significance and an underlying meaning. The story is set in the real town of Schenectady, New York and the word “synecdoche” is a figure of speech that refers to when a part of something is used to represent the whole, or vice versa. The story and its characters were not created as pure entertainment; they are representations of larger philosophical ideas about life and death.

Trying to interpret and evaluate this movie after one viewing is worthless; Kaufman spent over years working on the script before going into production. The fact that the overwhelming scope of ideas in the movie did not cause Kaufman to have a mental breakdown like the film’s protagonist is an astonishing creative achievement.

On second thought, this film could be interpreted as a metaphor that shows a self-conscious director pouring his whole self into the process of producing an ambitious, complex work of art. Synecdoche.

Author Bio: Joshua is an aspiring professional screenwriter and film director with an admiration for filmmakers who use the medium of cinema as an art form rather than pure entertainment. Currently he is attending film school at Brooklyn College while working on original screenplays and short films.