8. The Exterminating Angel (El Angel Exterminador, Luis Bunuel, 1962)

The opening shot of a cathedral is followed by a church choir performing the only non-diegetic music piece we will hear until the end of the picture. But the lack of background music shouldn’t commit one to high expectations of naturalism in this surrealist classic.

The story of the film, for those who do not know, revolves around a group of upper class guests attending a dinner party at one of their friends’ villa. The very evening is marked by unusual and unexpected departures by the staff, leaving ultimately only the butler to tend to the guests. After unexpectedly deciding to stay the night, they all eventually discover the next day that they are unable to leave the room.

The absurdity of the situation is accentuated by the lack of music which might have otherwise diverted the viewer’s attention from the on-screen events.

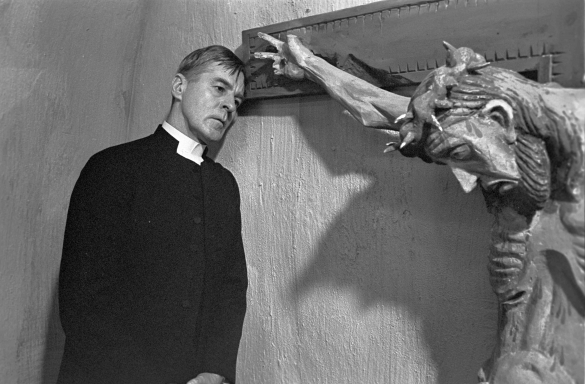

Bunuel was a controversial figure in his home country of Spain, which was at the time under the fascist dictatorship of Generalissimo Francisco Franco. He was exiled not once, but twice. After the Spanish Civil War ended, Franco banished him as well as plenty other leftist intellectuals, and eventually allowed him to return home almost thirty years later, and granted him rights to make a movie of his choice.

Bunuel, being a joker, decided to make Viridiana, a film which offended the religious sentiments of the ruling class so much that the infuriated Franco decided to banish him once again. The Exterminating Angel – the first film he made after his second banishment – is a gauntlet thrown in their face and the face of their fake morality.

One might be tempted to call the film symbolic, despite the real possibility that there is no symbolism whatsoever. Not for the most part, in any case. Bunuel himself claimed many times that it was futile to seek deeper meaning behind his dreamlike images.

7. Beyond the Hills (Dupa Dealuri, Cristian Mungiu, 2012)

When William Friedkin adapted William Peter Blatty’s novel, made the Exorcist in 1973 and thus introduced the subject to the mainstream film world, he inadvertently set the stage for plenty other similar films about the expulsion of evil spirits.

Consequently, exorcism was seen less as an exploration of people’s beliefs and prejudices, and more as a battle with real dangers of the supernatural. Mungiu used this trope radically different, by viewing the act of exorcism through the cold lens of a rational, objective observer.

Mungiu’s breakthrough film was a gut-wrenching story about an illegal abortion in the last days of Ceausesku’s dictatorship, which shocked and stunned the film world, left the audiences speechless and the critics unusually talkative. In was not just the brutal verisimilitude in his approach to the subject matter, but also the ability to show characters we could care about, and fear for. Beyond the Hills is a worthy successor, somewhat larger in scope, focusing on the delusions of a large religious group.

The story is set in a secluded woman’s monastery, which houses among others a young nun called Voichita (Cosmina Stratan) who came there after being released from an orphanage.

A childhood friend of hers, Alina (Cristina Flutur) came to visit, but her neuroses and drug problems led to her being falsely diagnosed as possessed by the devil. Instead of seeking professional medical help, the monastery superiors decide to expel the demon, even convincing Voichita to help them, which she reluctantly agrees to do.

This tragic story serves as an examination not only of prejudice and dogma, but also authority figures, paranoia and personal responsibility.

6. Rope (Alfred Hitchcock, 1948)

The master of suspense didn’t shy away from using music to increase the tension in his films. Psycho is just one example of many: The Rear Window, Vertigo, Rebecca, 39 Steps… they all feature a suspenseful score that tends to keep the audience at the edge of their seats.

In fact, the music of his films was so memorable that an eponymous soundtrack album was released in 1999 under the patronage of the Museum of Modern Arts. It features works by Hitchcock collaborators such as Bernard Herrmann, Franz Waxman, Dimitri Tiomkin, Roy Webb etc.

Aside from an opening theme, a modest melody that sets the mood by transitioning from playful to mysterious, no music is accompanying the scenes that follow. In fact, both the film’s tension, and its handling of characters rely on the lack of music. As the camera pans from the wide shot of a city street towards a covered window, the opening theme slowly dies out and is replaced by an abrupt scream.

In this instant the camera suddenly shifts inside to show the two perpetrators bringing their deadly act to its end, by slowly loosening the grip they held on a man’s neck. The silence is both frightening and frigid, and shows the act in all its ugliness.

The murderous pair are college friends Brandon (John Dall) and Philip (Farley Granger), indoctrinated by Nietzche’s theory of the superman, who committed the crime only to demonstrate their superiority over the victim, a schoolmate of theirs. They host a party which is attended by, among others, the victim’s father and aunt, as well as their former prep school housemaster, Rupert (James Stewart). David’s absence ultimately leads to suspicion and

The film was initially seen by the majority of critics as a “stunt“ and “novelty“ with respect to the technical aspects (long takes combined with static still shots which effectively mask most of the cuts between each shot). However, it ultimately became respected as a masterfully executed thriller and an exercise in the philosophy of morality.

5. Winter Light (Nattvardsgästerna, Ingmar Bergman, 1963)

Sweden’s most prolific filmmaker, the great explorer of the human condition, was often recorded as being dissatisfied with many of his films. In fact, he once remarked that the only film of his that he was satisfied with was Winter Light. “Everything is exactly as I wanted to have it, in every second of this picture.“ It is at the same time a very personal film, the making of which helped Bergman come to terms with himself. A curious trait of the film is that it features no music whatsoever.

The second part of his trilogy about man’s relationship with god (the first part being Through A Glass Darkly, and the third The Silence), it is a story about a small town pastor, Tomas Ericsson (Gunnar Björnstrand) whose faith in god is failing.

Just like Thomas is losing faith, his congregation has dwindled away to a handful of people. But those who are still there nevertheless rely on his help, just like Jonas (Max von Sydow), a depressed fisherman, or Märta (Ingrid Thulin), his ex-mistress who is still in love with him.

There is no divine intervention in the form of enlightening, godlike music. In his search for god, man is left to his own devices.

4. A Separation (جدایی نادر از سیمین, Asghar Farhadi, 2011)

Iran has a rich history of film, and Iranian cinematography is often considered to be one of the best. A milestone film, in a sense, is Farhadi’s A Separation, the one that won an Oscar for best foreign language film in 2011, and the first one from Iran to achieve that, not to mention reaping plenty of prizes on other festivals.

Farhadi himself is not a recent addition to the Iranian auteur community, having made films like About Elly and Fireworks Wednesday. The separation in question is of Simin (Leila Hatami) and Nader (Peyman Moaadi), a middle class couple with an eleven-year-old daughter Termeh (Sarina Farhadi).

Simin wants to leave the country dissatisfied with the state of affairs, but Nader will not leave his father suffering from Alzheimer’s. After the court judges the reasons for divorce insufficient, Simin moves back with her parents and Nader hires a poor, deeply religious woman to care for his father, a decision which brings into being a series of unfortunate events.

Many critics have praised the realism of the film – from actors playing their roles convincingly, to the lack of music throughout. In fact, there are a couple of instances of diegetic pop music playing on the radio, and a somber piano tune during the end credits.

3. M (Fritz Lang, 1931)

Being one of the capital directors of the expressionist movement, and starting off as a silent film director, Lang tended to focus on the visual. The stretching shadows, the reflecting surfaces, all testify to a desire not only to tell as much as possible with visual clues, but also to base a film’s atmosphere on them.

But unlike many of his fellow film artists, he did not believe that one requires music just to fill up a void, but rather felt that silence can say more. Even though M was Lang’s first sound film, he obviously didn’t feel the need to incorporate music just for the sake of it, but turned to experimenting with sound instead. This is the exact reason why his serial killer thriller from 1931 still holds up well after all these years, and manages to keep the audience on the edges of their seats.

There is a musical leitmotif however, but instead of having a theme played in the background every time a character enters a scene, Lang chose an innovative approach by having the character whistle a melody himself – In the Hall of the Mountain King from Edward Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite No. 1. The character in question is Peter Lorre’s serial killer whose crimes directed against children terrorize a large German city.

Influential members of the underworld eventually decide to organize and hunt him down, because the increasing police raids constantly disrupt their own criminal activities.

2. Hidden (Caché, Michael Haneke, 2007)

Films as entertainment and films as art unfortunately live in segregation nowadays, with the former occupying large cineplexes while the latter are housed in quaint arthouse cinemas. Haneke’s Hidden is one of the films that successfully broke the barrier and found their way in mainstream culture especially owing to the fact that it used genre conventions to present a genre-transgressing story.

Similar to David Lynch’s Lost Highway, it starts off with an affluent married couple terrorized by mysterious videotapes of their home. They are Georges (Daniel Auteuil) – a TV host on a book show, and Anna (Juliette Binoche) – a literary publisher. Their cozy lives are upset by the already mentioned videotapes, which seemingly come from a source from outside their house.

They soon start arriving accompanied by disturbing crayon drawings that hint to a long-kept secret of Georges’, which involves an Algerian boy from his childhood home.

Avoiding a supernatural turn that Lynch chose, Hidden remains in the realm of the possible, but that doesn’t mean that this is a straightforward thriller. Instead of a whodunit, it is primarily an examination of one’s guilty conscience, as well as the painful history of France and its colonies. Similar to the effect seen in M, it is the silence that packs the greatest punch in terms of tension.

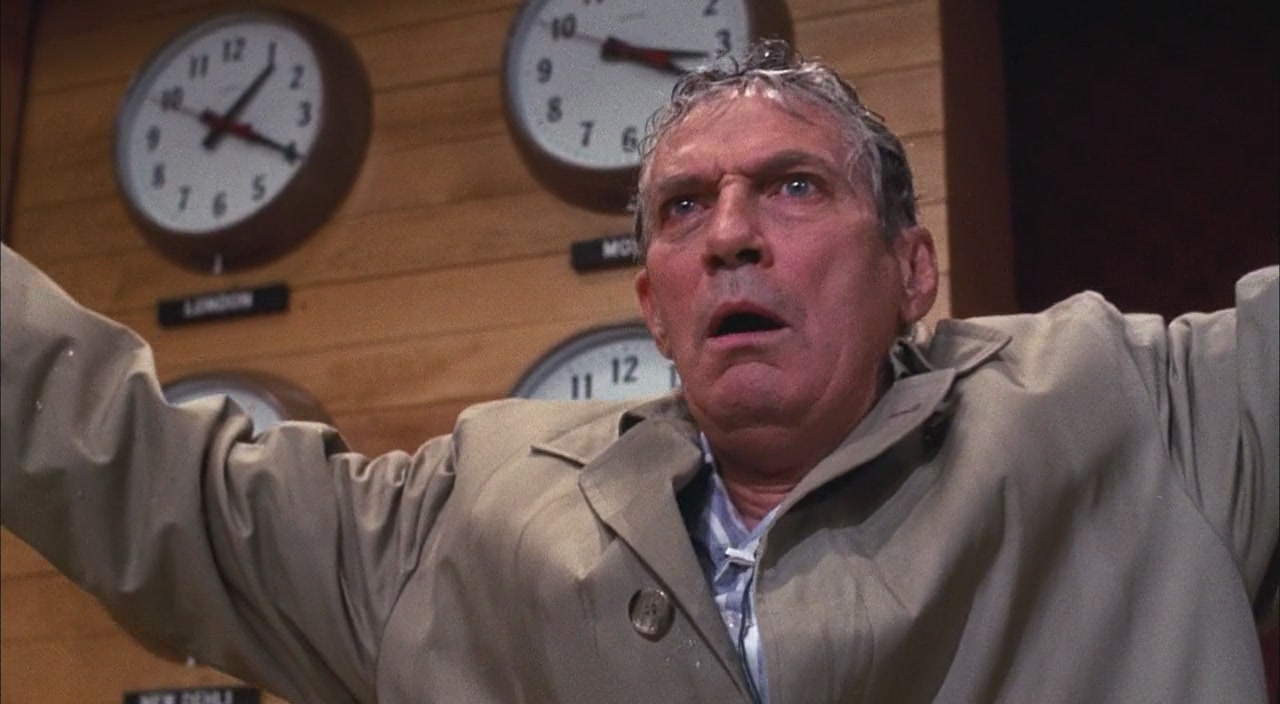

1. Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976)

A network programming executive is sitting on the edge of her bed naked, watching television, while her lover is gently kissing her body. Her gaze is nevertheless fixed at the TV set, even when she curtly tells him to “knock it off“. In the very next scene she is walking the corridors towards her office. Her pace is determined.

So much that the woman walking behind her is nearly struck by the door that she inadvertently failed to hold for her. She, Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway), is “television incarnate… indifferent to suffering, insensitive to joy“ as another character, a disillusioned newscaster from the golden days of television remarked (Max, played by William Holden).

Although Sindey Lumet’s Network will forever be remembered by the vehement monologue of Howard Beale (Peter Finch), who is “mad as hell and won’t take it anymore”, the true star of the show is Faye Dunaway in her role of TV’s Patrick Bateman, bar the killing.

Paddy Chayefsky’s screenplay perfectly balances between naturalistic (especially with the industry jargon) and melodramatic, while at the same time maintaining a hyper-intellectual feel, with characters sounding like philosophy majors on cocaine.

Network is by no means Lumet’s only film without a musical score. The Offence, Dog Day Afternoon, as well as 12 Angry Men are all marked by a lack of non-diegetic background music. Nevertheless, in Network the lack of music is more telling than anywhere else, emphasizing the arctic cold of the business world.

HONORABLE MENTIONS: The Birds (Alfred Hitchcock, 1963) and No Country for Old Men (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2007)

Both interesting thrillers may at first seem to be lacking a musical score, but the fact of the matter is that their composers (Bernard Herrmann and Carter Burwell, respectively) actually used various noises to accentuate the lurking dread.

Author Bio: Ivan Maksimović is a recent anthropology graduate from Serbia, currently doing an internship in a museum. He views film as an important outlet for ideas, especially those regarding social problems.