This list is about exploring films that aim to push the boundaries of cinema. It serves as an introduction to the concept of visual narration in film.

15. Only God Forgives (Nicolas Winding Refn, 2013)

Combine elements of the western and gangster genres and put them inside Bangkok, which looks like a city with a sci-fi background. Then, develop characters while unfolding a story without dialogue or a voice-over narrative. Add no background stories whatsoever, as that isn’t what really matters in this film.

“Only God Forgives” plays like an avant-garde exercise on visual drama, and through the dramatic and violent expression of elements and forms on the screen, the film creates the feeling of a myth. It’s like planting a seed in the ground and having it gardened and growing as the public watches it.

This film is about having control over the uncontrollable. It is about living with that thing that transcends one’s self. Maybe “Only God Forgives” is about forgiving one’s self for whatever one may have done. The visual style is the most important tool here, in order to cinematically tell the story as it needs to be told. This is why the use of dialogue is reduced to a minimum.

14. Angst (Gerard Karlg, 1983)

A moving tree is represented by a crane shot. There is an odd conceit on the part of the filmmakers who decided to shoot the life of a serial killer by mostly observing the character from above. The sense of dread and solitude is more significant once the character has been released from jail. Inside the iron bars and concrete walls, it feels like being inside a comfortable egg, with a melodic and harmonious song generating a mood of poetic calm.

The language here is technical but it feels natural and grounded. It is filmed in such a way that the viewer is almost unaware of the technique. It does not bother but rather accelerates the experience, the horrifying notion of the passing of time. There is no story but a representation of moments within a single day. The film feels like a reality TV show or a found footage movie, yet it’s neither of those. This movie shows you how to use the camera in a unique way.

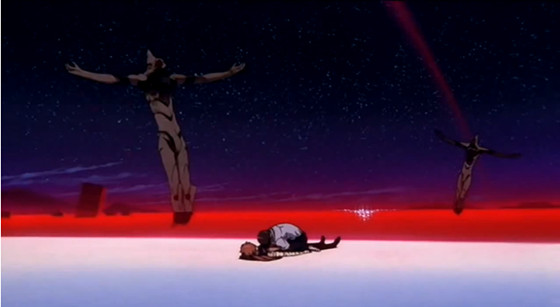

13. The End of Evangelion (Hideaki Anno, 1997)

This film references the television series, “Neon Genesis Evangelion”. Sometimes stories need to be seen from the beginning; they actually demand that the spectator watch the back story, to know the situations that concern the characters. This movie continues the original story that somehow doesn’t have much to do with the original ending, as the original series was canceled.

The movie works quite well on its own terms and is separate from the TV series in every way possible. It works if one just watches this movie and totally avoids the series. However, it may be better to have seen the series, since one may want to watch the series for the first time or watch it again. There are elements of a live-action feature film, such as people being filmed. The walls have been breached and the ending is just a sorrowful beginning, filled with black humor.

The pace of the story is perfect with every character having their moments, and they all are well drawn. The visual narrative excels, the cinematic construction of every scene is well paced, and there is always time for contemplation. Here, the use of the visual moving language that is cinema hits the bar, using every strength of its creators to the limit.

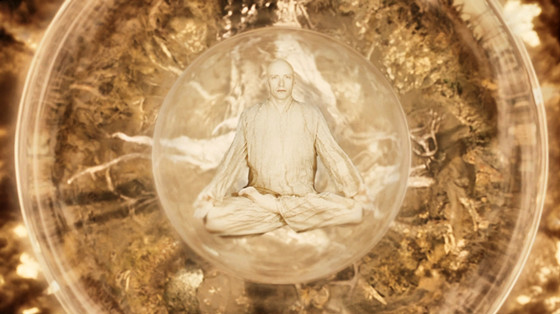

12. The Fountain (Darren Aronofsky, 2006)

Only a single lifetime is needed to experience so many emotions. A person must find who they are and transcend the limits of the ego, go outside of the bubble that contains the self, and be released from the pain of attachment to what is known.

The devastating nature of death is the ultimate ecstasy, more so when it is accurately translated to the language of cinema. Just for the sake of creating visual poetry that is beautifully and convolutedly shown, nothing is left out. Everything that needs to be seen is there on the screen.

There is a mathematical precision to the whole look of this film and the way it was edited. The cinematic flow feels totally clinical, but it also feels inspired by mythology. The creators of this movie were aware that combining elements as diverse as mythology and science into one entity can create a successful piece of filmmaking art, though highly contradictory in its form and structure. Every change of pace and time frame feels out of context, but it works.

11. Tale of Tales (Yuryi Norshteyn, 1979)

War is a never-ending tale of sadness and madness in contrast with beautiful childhood memories, such as big bulls with big horns, grey wolves, dance clubs, cars, trees, and family picnics outside on the open field in time for the setting sun.

Capturing the essence of folklore is the most important aspect of this film and the use of several forms of animation, specifically that of stop-motion, gives a dramatic and relevant feel to the wartime climate.

This 30-minute animated film juxtaposes moving images connected by a feeling of dread, loss, and kindling memories, which should be remembered in an imaginative and positive light in the face of the negativity of war and death.

In this movie, the camera hardly moves. At times it captures different scenes in different times and moments that look just like paintings, cut in time to background music. This animated short film proves that animation has an unknown universe that has yet to be explored.

10. Enter the Void (Gaspar Noé, 2009)

This movie is based on “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”, or “Bardo Thodol”. It is actually a very loose adaptation, about a person unaware that he will die shortly while reading the book, without finishing it. The movie plays with the audience, going very slowly and repetitively.

It works like a stroboscopic effect of continuous movements connected to each other and going back to the past only to return to the present without substance, and through POV shots, we can experience what the person is “living” in his afterlife. The characters who are still alive seem more dead than the dead. It feels like a pictorial representation of memories of the character, who needs to move away from them.

The reason for this film’s existence here is the experience that can only be achieved through cinema. One can forget about how the scenes are cut, or even the technical achievement of the production. The most important part is the immersion of the viewer through the adventure into limbo, a phantasmagorical adventure into the netherworld as told in a masterful and respectful way, in the only way possible it could have been told: through the eyes of a camera.

9. Angel’s Egg (Mamoru Oshii, 1985)

This film is set in an apocalyptic otherworldly aftermath, based on the concept of Noah’s Ark, in which a bird that was sent to look for ground never came back. The picture takes a minimalistic approach to tell the story. The visuals include baroque scenery, fish sculptures all around, fishermen, a wandering man holding something that looks like a cross, and a little girl who very carefully tends to an egg inside her clothes.

There is no need for assumptions or interpretations, but one can praise the dialogue. There are biblical references, but it goes beyond that. It seems as though the dialogue and the plot are used to represent the world, not symbols nor allegorical references. They show a world turned into a city, an island, a place where a boat stays like a relic, intact like a black sculpture, a static shadow with no definitions or details.

The virtues of the film include the smoothness of the cinematography, with every cut meticulously chosen. The storyline itself is a presentation of the world, the travels of the two characters existing in a fantasy landscape. The sound design highlights a profound musical selection in helping to conjure a cinematic achievement often achieved only by some of the most magical live-action movies ever made.