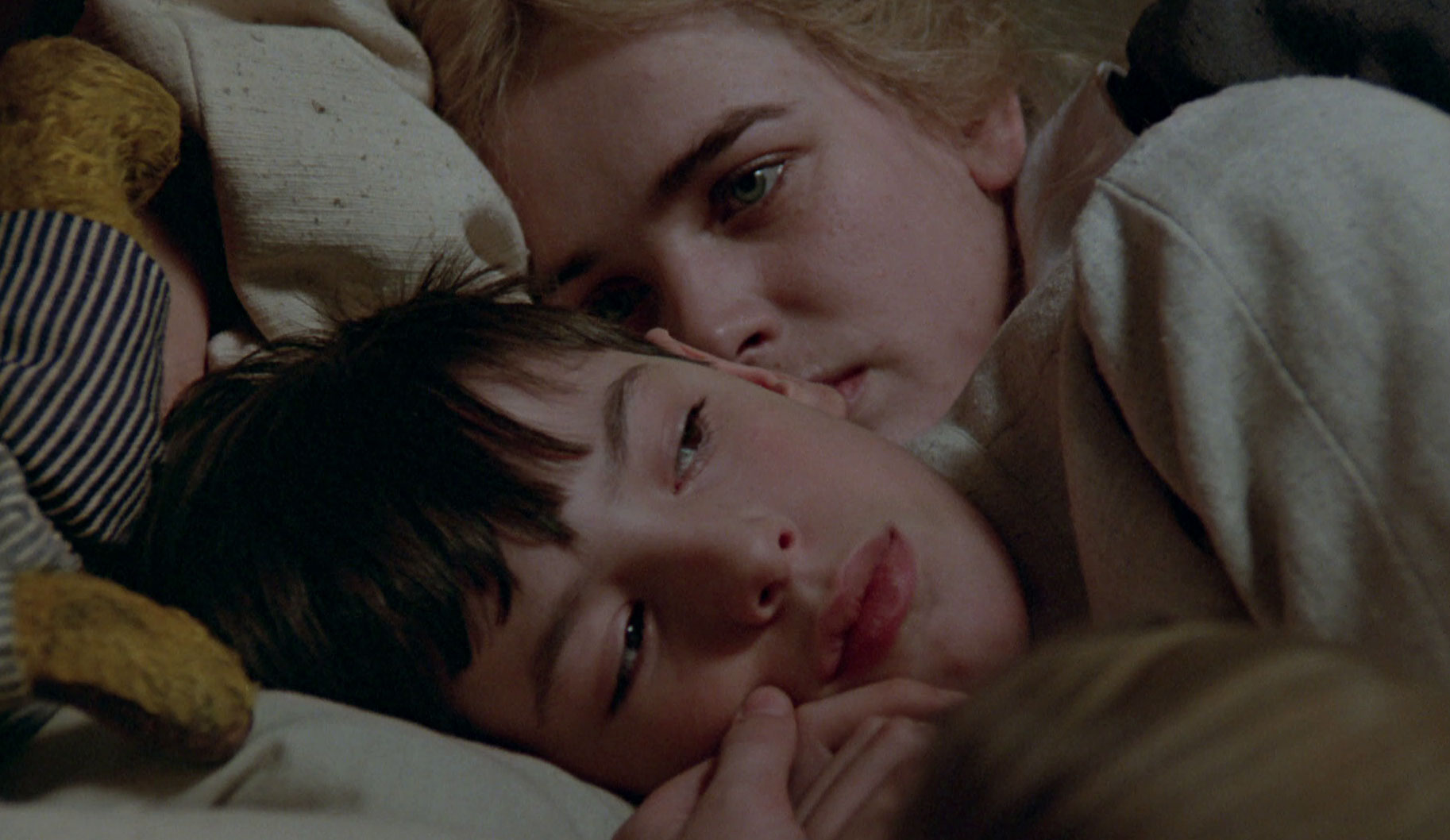

5. Fanny and Alexander (1982)

Running Time: 3h 8m (Theatrical Version) & 5h 12m (TV Version)

One of the most astonishing things about Ingmar Bergman is his ability to convey an extraordinary range of complex emotional states on-screen. Love in Bergman’s cinema is often accompanied by great cruelty; sex is often soured by enmity or disaffection; and faith often brings a torturous sense of inadequacy and self-disgust. His films are detailed, often uncomfortably intimate explorations of the ambiguities and absurdities of human existence.

On the surface Fanny and Alexander, a period drama that spans two years in the life of a well-to-do Swedish family, seems rather different. It is not just in colour, already a rare thing for Bergman, but it positively bursts with colour. There is a similar use of iridescent, opulent mise en scène to The Leopard, and with a similar multitude of supporting characters. Candle light exposes the soft red and golden hues of vast drawing rooms as we are presented with a visual warmth never before seen in the work of the Swedish master.

And yet the genius of the films is that beneath this startling change in visual aesthetic, we find a film that is just as intimate, as profound, and as devastating as any of Bergman’s other works. It may be a period drama, and may take place over the course of a few years, but this is not a film of wide-angle panoramas and bombastic crane shots; it is a film of lingering close-ups where a change in emotional temperature is detectable only through the most subtle of facial expressions.

The story of the film is revealed largely through the perspective of the titular Fanny and Alexander, the young children of one of the three Ekdahl brothers.

The adult drama is thus played out through the bountiful imagination of a child: a deceased father carries on his parenting as a benevolent, melancholic ghost, a cruel stepfather becomes a murderous devil surrounded by supernatural terrors, and an antique store becomes an unreal maze hiding sinister magic. Wonderfully wistful, this is one of Bergman’s best, and most surprising, films.

4. Andrei Rublev (1966)

Running Time: 3h 25m

Russian master Andrei Tarkovsky’s second film, a loose biography of the life of Russia’s most famous icon painter, is often regarded as his greatest. And indeed it is a film of such immense aesthetic power that it is hard to know where to begin.

Although nominally a biographical work, Tarkovsky’s film is actually more concerned about depicting the specific geographical, cultural, and spiritual details of the 15th century Russia in which Andrei Rublev lived. Rublev wanders through the Russian countryside observing and experiencing the strange, erotic mysticism of pagan ritual, the horrifying violence of Tartar raids, the debilitating effects of famine, and the waning faith of a disaffected peasant population.

You could argue that the barren, forbidden Russian landscape is reflective of Rublev’ s famously ascetic approach to icon-painting, but in fact the film is more concerned with portraying the extremes of corporeality, a contrast to the expressive bareness of Rublev’s iconographical design.

It is a film about harsh violence, sweat-inducing toil, carnal lust, and starvation. And yet Tarkovsky’s inimitable style makes this brutal world beautiful; the gentle snowfall and creeping fog that permeate each frame moulds the frozen fields and muddy lakes into grand, cosmological landscapes.

Finally, to watch the ending is to witness perfect harmony between two artistic media. The last five minutes of the film switches to colour as Tarkovsky’s camera slowly, and elegantly, pours over the actual icon paintings of Rublev.

After almost three hours of black-and-white cinema, to be suddenly exposed to such an explosion of colour and light is an experience like no other; it is affecting in a way that cannot really be put into words. To watch this sequence is to be in the presence of two masters of their craft. Unforgettable.

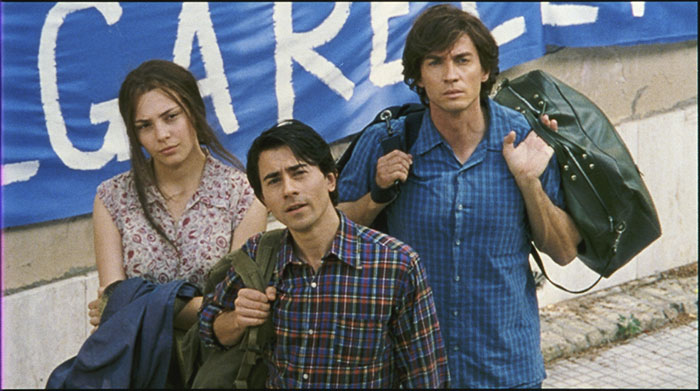

3. The Best of Youth (2003)

Running Time: 6h 40m

Once again we return to the vicissitudes of Italian history as experienced through the eyes of one particular family. From the drastic political and cultural changes that eventually gave shape to a unified Italy in the 19th century, we move to the latter half of the 20th century with The Best of Youth; an enthralling six-hour saga by Marco Tullio Giordana that charts the lives of two brothers living in Italy from 1966 to 2003.

The film is a sublime cinematic constellation of the triumph and tragedies of a nation as elided with the triumphs and tragedies of two men. As one of the brothers grows their hair and engages with the hippie movement, the other shaves his and joins the police force. Both, in very different ways, experience the violent unrest of Italy’s ‘Years of Lead’. At one point one of the brother’s talks with his best friend about Italy’s transparent banking initiatives while they both rock their new-borns to sleep.

It is an image that epitomises The Best of Youth- the film is as concerned with Italy’s tumultuous history as it is with the way in which each brother deals with the profound joys, and inescapable melancholy, that come with aging. Like The Leopard, it is a film that engages with history in a complex, intelligent, yet intimate manner. It is hopeful without being saccharine, sombre without being maudlin.

Furthermore, the screening time of the film is extremely important to its effect. The brothers’ often reflect on their youth, on the way in which it has shaped the paths that their lives took. Their wistful reflections are matched with ours, as we remember those carefree opening scenes with three or four hours distance from them.

Such a weighty, unusual temporal distance means that we, like the brothers, are engaged in a game with memory. This leads to a unique, involving relationship with character subjectivity. Another rare, and powerful, cinema experience.

2. Sátántangó (1994)

Running Time: 7h 30m

Sátántangó exists within a strange temporal vacuum. Time does progress, does not move forward, but is immobilized by the desolate, muddy quagmires that make up the film’s pastoral setting. The film follows the collapse of farming collective in Hungary as the already fractured community becomes increasing polluted by mistrust, deception, and debilitating alcoholism.

The film is still, but in the most moribund sense of the word, as the villagers are either too overweight, too drunk, or too depressed to move around much; indeed many scenes begin with eerie, sepulchral tableaux in which characters seem to be stuck to the frame like speared butterflies.

The film’s sense of immobility, of extreme stasis is reflected by director Béla Tarr’s use of extremely long takes (the average shot length is 2 and a half minutes); an aesthetic that shares many parallels with the aforementioned Norte. This formal approach, coupled with a seven hour running time, makes Sátántangó one of the most intimidating works in the history of the medium. But it shouldn’t be, because within all the boggy bleakness is great beauty and a brilliantly misanthropic sense of humour.

The sterile landscape is coated with a gauzy monochrome- a defining feature of Tarr’s oeuvre- that lends the whole film a desolate, yet ethereal beauty. Furthermore, this is one of the purest examples of Beckettian cinema ever to be produced, as we watch the characters casually curse, reject, and betray each other; their collective life-force seeping out of the frame as they unknowingly slump towards a sort of spiritual apocalypse.

And we laugh. We laugh at their pathological self-interest, their drunken buffoonishness, and their debilitating paranoia. This how the world ends, not with a bang, but with a chuckle.

1. Shoah (1985)

Running Time: 10h 13m

Shoah is number one on this list not because it is the longest of the group, running at 10 hours and 13 minutes, but because it is a work that transcends the conventions of the documentary format to become something else entirely.

It is a vital document of verbal, and visual testimony regarding an event of such immense destruction that it has often defied historiographical conceptualization. In particular, attempts to render the holocaust on screen have always been met with serious, complex questions regarding the aestheticization of such an immense historical tragedy.

Lanzmann’s Shoah does not reconstruct, does not use footage of the camps, nor does it attempt to attach a linear, chronological narrative to the events in Chelmno, Treblinka, Auschwitz-Birkenau, and the Warsaw Ghetto. Instead it is a collection of voices; voices of the victims, bystanders, and perpetrators of the mass death that took place in occupied Poland.

The film is about the evocation, and the conservation, of memory; it collects voices not in the hope of building up a holistic view of the destruction, but in order to preserve the most important maxim to emerge in holocaust discourse: never forget.

At several points in the film, survivors break down during their testimony of events; they are overwhelmed by the horror of what they witnessed. And yet Lanzmann urges them to continue, repeating that their testimony must be documented; he understands that they must talk, and we as viewers must listen.

Finally, Lanzmann often cuts from these testimonials to long, contemplative shots of the Polish countryside where the camps once stood. These shots supply a visual, temporal, and emotional respite from the ungraspable horror of the testimony that we hear; they allow us to reflect upon what we have heard, to fill this starkly beautiful landscape with our own thoughts. The shots are unlike anything else in the history of cinema, as still and as meaningful as silent prayer.

Author Bio: Tom Jackson holds an undergraduate and masters degree in Film. He first went to the cinema at age 4 to see Toy Story, and never really left.