14. Franceso giullare di Dio (1950, Roberto Rossellini)

It is a curious fact that two of the greatest depictions of spiritual Christianity were made by avowed atheists: Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Matthew and Rossellini’s cinematic treatment of the life and teachings of St. Francis and the early Franciscans, Francesco giullare di Dio (Frances, God’s Jester a.k.a. The Flowers of St. Francis).

Co-scripted with Federico Fellini and shot in a neorealist manner with non-professional actors (including thirteen actual Franciscan monks), the film unfolds in a series of vignettes based on the early days of the Franciscan Order; some comic, many deeply touching – with the most moving of all the scene in which Francesco embraces a leper, overcome by the immensity of the afflicted man’s suffering.

Initially poorly received, it has since risen in stature to become one of the most well regarded films of the neorealist movement, drawing praise from directors such as Scorcese, Pasolini and Truffaut (with the latter describing the picture as ‘the most beautiful film in the world’). That beauty lies not only in its painterly cinematography, but also in its spirit of simple profundity built upon the saint’s timeless ethos of humility, compassion, faith and sacrifice. A film to restore one’s faith in humanity.

13. The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962, Robert Bresson)

Winner of the Special Jury Prize at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival, Bresson’s film charts the final days in the life of Joan of Arc, the French heroine who led her nation against the English during the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453) before being burnt at the stake for heresy at the age of 19.

Favouring a largely static camera and a limited range of angles, Bresson’s spartan approach is the antithesis of the expressionist melodrama of Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, most notably in their respective use of actors.

Having criticised the overblown performances in Dreyer’s film as ‘grotesque buffooneries’, the French director opts for deliberately understated performances from his non-professional cast. Their acting is strong enough (especially Florence Delay as Joan), but it is their limited range Bresson primarily values, ensuring the impact of their lines hit home without unnecessary embellishment or distraction. That those lines were drawn from actual court transcripts of Joan’s trial lends a haunted, haunting quality to the film as though the viewer is in direct communication with the ghostly voices of the past.

The perfect marriage of form and content, even the film’s sole anachronism serves a purpose – Joan’s modish 60s haircut emphasising that this was a teenage girl, not much different from those of today, fighting for her life against the combined forces of church and state.

At only an hour in length the spare quality of the film belies its emotional impact and its final shot of the charred stake stands as one of the most moving and horrific images in cinema history.

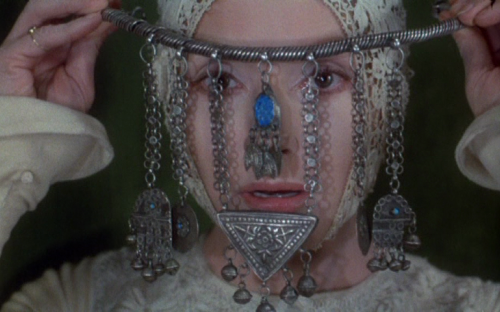

12. Alexander Nevsky (1938, Sergei Eisenstein)

While Alexander Nevsky is set in 1242, its scenario could just as easily be playing out in the year in which it was completed, and when the Knights of the Teutonic Order (swastika-like crosses emblazoned on their arms and banners, their infantrymen sporting Stahlhelm-esque helmets) take the city of Pskov in an orgy of women and baby burning, Russian audiences would have no difficulty recognising the modern foe they represented.

Alexander Nevsky may be propaganda, but it’s of the superior sort. Ably assisted by a majestic score by Sergei Prokofiev and Edouard Tisse’s resplendent cinematography, Eisenstein was able to transform the crudest of political metaphors into great art. Nikolay Cherkasov gives a suitably iconic performance as the titular prince summoned by the people to defend the Russian homeland, while the climatic battle on a frozen lake remains as thrilling as ever.

11. Throne of Blood (1957, Akira Kurosawa)

Considered by the American literary critic Harold Bloom as the most successful film version of Macbeth and by many as Kurosawa’s finest work, Throne of Blood is a visceral adaptation of Shakespeare’s Scottish play which transposes the tale to Japan in the 1500s.

Combining Elizabethan tragedy with formal elements taken from the Noh theatre, Kurosawa sets the classic tale of moral turpitude, ambition and duplicity in a dank and rotting atmosphere of death and decay, bringing to the forefront the supernatural elements as well as its underlying air of fatalism.

In keeping with a film whose original Japanese title literally translates as ‘Cobweb Castle’, the latter is represented by recurring images of entrapment, most notably the scene where two characters become lost deep within the film’s Cobweb Forest and encounter the prophetic witch (reduced from the three in the original play) who is presented not only as a Fate measuring out the thread of the characters’ lives but also a spider at the centre of a web from which there is no escaping.

Kurosawa regular Toshirô Mifune gives a ferociously animalistic lead performance, equally matched by Isuzu Yamada’s ghostly Lady Asaji Washizu (surely the most chilling Lady Macbeth ever committed to celluloid), while the scene in which the hero is pinioned to a fortress gate by a flurry of arrows provides one of the iconic images of world cinema.

10. Blanche (1972, Walerian Borowczyk)

Loosely based on Mazepa, a drama by the Romantic poet Juliusz Słowacki, the fairytale-like Blanche is Borowczyk’s typically stylised, idiosyncratic take on the Middle Ages. Set almost entirely within the walls of a French chateau, the film centres on the much younger wife of a 13th century nobleman and her attempts to resist the unwanted affections of various visitors, including the King and his philandering page.

Part bedroom farce, part chanson d’amour and finally bloody tragedy, Blanche eschews realism for a highly distinctive mise-en-scène that achieves a similar effect to the way a painting may reveal more about an age than thousands of pages of historical manuscripts.

Evoking the look of medieval tapestries or friezes in flat but artfully arranged compositions, Borowczyk often favours rigorously framed head-on shots, which often devote as much attention to inanimate objects and animals as to the faces of his actors, but always give a palpable sense of life continuing outside and beyond the frame. It also achieved its uniquely evocative flavour by the then highly innovative deployment of period music, particularly arrangements based on the Carmina Burana songbook.

The cast includes Jacques Perrin, Georges Wilson and a late performance from the great Michel Simon, but as in Borowczyk’s previous film Goto, l’île d’amour, the real star of the show is Ligia Bernice, the director’s wife and muse. A limited actress but a beguiling screen presence, she is the quintessential bird in a gilded cage in this tale of male desire and power politics. A film with all the singular brilliance of its creator, Blanche is an excellent introduction to one of cinema’s truly unique filmmakers.

9. The Virgin Spring (1960, Ingmar Bergman)

Dismissed by Bergman as a pale imitation of Kurosawa (even in spite of winning an Academy Award and praise from the great Japanese director himself), The Virgin Spring tends to be overlooked in the Swedish auteur’s considerable oeuvre. But for all the Swede’s misgivings, it’s arguably a more accomplished picture than his more celebrated The Seventh Seal and its quite terrifying vision of medieval Sweden easily matches it in impact.

Based on a 13th century ballad, the plot revolves around two shocking acts of violence: the rape and murder of a young girl on her way to Sunday Mass by a group of goatherds, and the subsequent vengeance visited by her father upon the perpetrators. But it is Bergman’s evocation of medieval Sweden that leaves the biggest impression.

Depicting a nation whose burgeoning Christian faith is still haunted by remnants of its pagan past, the film is remarkably even-handed in presenting the distasteful elements of either belief system with its vision of a stern, self-flagellating Christianity no less sinister than the darkly seductive world of Odin worship.

Filtered through Bergman’s existential pessimism, even the apparently miraculous emergence of the titular spring that forms on the site of the murdered girl’s body towards the close of the film is tinged with dark ambiguity.

Is it no more than a coincidence of nature, a force wholly indifferent to the fate of humankind? Or is it, as the characters seem to take it, a sign of God’s grace? And if the latter, what kind of deity requires the brutal murder of an innocent girl before showing his hand? Bergman’s beautifully photographed but deeply chilling picture provides few easy answers.

8. Onibaba (1964, Kaneto Shindô)

Of all the Japanese period films charting the nation’s feudal age, Shindô’s Onibaba is the most savage. Set in a 14th century Civil War-ravaged Japan, the film tells the story of a mother and daughter-in-law who eke out a precarious living by ambushing and murdering samurai within the seven-foot-high susuki grass fields before disposing of the bodies in a deep pit and bartering the armour and weaponry for food. But when a neighbour returns from the wars and settles down next to the women, a no less frenzied sexual jealousy threatens to destroy the pair’s relationship.

Shindô’s darkly erotic tale takes place specifically in the Nanboku-chô period (1336-1392), when the country was divided into two warring empires in the north and south – an age described by the director as one where the ordinary men and women, forced into hiding themselves in the grass, ultimately survived by maintaining their sexual relationships.

But if Shindô intended his film to be a celebration of sexuality and the capacity of humans to overcome hardship, it’s a highly ambiguous depiction – one in which his characters are reduced to their most base and primitive impulses in a desperate struggle for survival.

With admirably uninhibited performances from its central trio of Nobuko Otowa, Jitsuko Yoshimura and Kei Satô, a frenetic score of avant-jazz and tribal drums by Hikaru Hayashi, and graphic scenes of sex and violence, Onibaba makes for a visceral cinematic experience, but through the power of its images (particularly those hypnotic shots of the swaying grass fields) one filled with moments of almost serene beauty.