7. The Valley of the Bees (1967, František Vláčil)

Released in the same year as Vláčil’s magnum opus Marketa Lazarová and likewise set in the 13th century, The Valley of the Bees charts the extreme consequences that arise when human passions are repressed and distorted by religious and ideological fanaticism.

After years of hardship within a society adhering to the precept that suffering is the way to God, Czech nobleman Ondřej of Vlkov makes his escape from the Order of the Teutonic Knights and returns to his childhood home in Bohemia. But he is soon tracked down by his former companion Armin von Heide, a particularly zealous knight who has pledged to return Ondřej’s soul to the Order.

A far more straightforward film in terms of its narrative structure than Marketa Lazarová and while not quite as aesthetically daring, it still contains some breathtaking images. There is beauty both in the austerity of the Baltic coastal setting and in contrasting scenes set in Bohemia containing a vibrancy and use of light that shines through the black and white film.

Some of the most memorable images are also some of the most horrific, such as the nightmarish ballet of a deserter knight plunging into a pit of ravenous dogs or a nocturnal sword fight set against a backdrop of smoking kilns.

As he had done in his earlier film, Vláčil manages his trick of immersing us in a world that appears almost unrecognisable from our own, allowing us to identify with characters even when their actions appear inexplicable.

When Armin is compelled to his shocking act of violence towards the end of the picture, it seems beyond comprehension and yet also perfectly in keeping with the film’s logic and internal conflicts. It may appear an alien world, but in a 21st century still plagued by dogmatism and religious extremism it is one we are encouraged to recognise as our own.

6. King Lear (1971, Peter Brook)

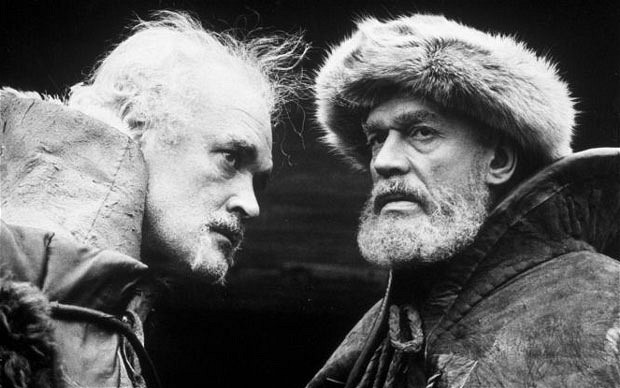

Shakespeare’s tragedy of kingship may have been written in the Elizabeth Age but it’s a work firmly rooted in the Middle Ages – its focus on the king-father as a symbol of the authority of the past, primogeniture, astrology and dowry all highly characteristic of medieval culture. Brook’s King Lear belongs to this tradition, even if the film’s stripped down aesthetic could just as easily place the scenario in the Dark Ages or some post-apocalyptic future of murder and societal collapse.

If Kurosawa’s Ran was an autumnal tale of fading regal grandeur, Brook’s King Lear is a bleak midwinter of despair, decay and death. Set in a barren landscape rendered in stark monochrome by Henning Kristiansen’s crepuscular cinematography, Brook’s austere take owes as much to Beckett and Bergman as it does to Shakespeare.

While that reductive approach combined with the director’s nihilistic reading may have irked the purists (one early review disparagingly dubbed the film ‘Brook’s Night of the Living Dead’), few productions penetrate to the dark core of the tragedy quite so effectively.

In keeping with the original tale, it’s a violent and unremittingly bleak picture, but like the best of tragedy strangely exhilarating at the same time. And with a cast that includes Patrick McGee, Jack MacGowran and Irene Worth, spearheaded by a muted but magnetic lead performance from Paul Scofield, the acting is of the highest calibre.

5. Ivan the Terrible: Parts I & II (1944/1958, Sergei Eisenstein)

Having impressed the authorities with his historical epic Alexander Nevsky, Eisenstein was encouraged to do the same for another historical figure: Tsar Ivan IV. This was to prove more of a challenge, however, for Ivan (as his epithet suggests) was one of the more notorious figures of Russian history.

As the last ruler of the nation’s medieval period he was responsible for uniting the formerly disparate states of Russia and for expanding the edges of her empire at an unprecedented rate, but at the same time his reign is associated with extreme ruthlessness and brutality (beating his pregnant daughter-in-law so savagely that she suffered a miscarriage, crushing his own son’s skull with his staff – and that was just his family).

For Stalin – no slouch himself in the tyranny stakes – this was exactly the sort of strong leader he wished to emulate; the Soviet regime, with its penchant for rewriting history, now wished to present Ivan as a hero.

Part I of the planned trilogy of films went to plan, receiving a Stalin Prize for excellence, but Part II, which presented Ivan in a considerably less heroic light, was not so well received. The film was immediately banned and would not be screened until 1958, ten years after Eisenstein’s death and five years after Stalin’s.

It is not difficult to see why. While Stalin and his party anticipated a portrait of a strong leader triumphing, Eisenstein gave them a nightmarish study of paranoia and moral corruption.

Headed by a crazed, almost inhuman performance by Cherkasov (barely recognisable from his earlier Alexander Nevsky), the films combined influences as disparate and as unlikely as German Expressionism, kabuki theatre and Disney, and even included (years before Mel Brooks’ The Producers) a song-and-dance routine performed by a chorus-line of mass-murderers (the Tsar’s secret police force, the oprichniki) led by one of Ivan’s henchmen dressed in drag.

As such, the Ivan films can hardly be described as realistic historical documents, but in resorting to the fantastic and surreal Eisenstein perhaps gets closer to the truth of what it must have felt like to actually live through the tyrant’s terrible reign.

At once the most elaborate act of career suicide in film history and Eisenstein’s greatest achievement, the Ivan films are testament to the genius and the courage of one of cinema’s true greats.

4. The Seventh Seal (1957, Ingmar Bergman)

Bergman’s key themes of spiritual uncertainty and the meaning of life in an apparently Godless universe were given their most stark depiction in The Seventh Seal, the tale of a knight who returns from the Crusades to a plague-ravaged 14th century Sweden where he encounters Death. One of the most iconic films in world cinema, its endlessly homaged and parodied image of Max von Sydow’s knight engaging the Grim Reaper in a game of chess recognisable even to those who have never seen the film.

While historians have pointed out the film’s numerous anachronisms (the last significant Swedish crusade took place in 1293 while the Black Death did not strike Europe until 1348, and witch hunts did not become widespread in Sweden until the 15th century), it is the atmosphere and look of the Middle Ages that Bergman so convincingly captures.

That iconic image of Death and the knight playing chess was inspired by Albertus Pictor’s Täby Church fresco, while the famous dance of death, or danse macabre, image towards the end of the film was a familiar medieval motif. Underneath it all is an evocation of an age suffused with religious hysteria and eschatological dread that certainly feels authentic.

In a film filled with memorable set-pieces the chess scene gets most of the attention, but for sheer spine-chilling impact it’s hard to beat the moment when Bengt Ekerot’s Grim Reaper finally comes to collect his harvest. Winner of the Special Jury Prize at the 1957 Cannes Film Festival, almost sixty years later Bergman’s atmospheric allegory has lost none of its power.

3. The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928, Carl Theodor Dreyer)

Often ranking highly in lists of the greatest films of all time, Dreyer’s final silent picture is an expressionistic take on the last days of the Maid of Orleans that for many stands as the pinnacle of silent filmmaking.

Apart from its Eisenstein-inspired finale where Dreyer takes some historical liberties as the crowd storm the burning stake, The Passion of Joan of Arc is essentially a chamber piece, albeit one in which human faces attain the immensity of landscapes.

Bresson famously voiced his distain for the ‘grotesque buffooneries’ of Dreyer’s performers, and there’s truth in the charge; the film’s cast of grimacing torturers and leering judges (including the playwright Antonin Artaud and a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it early appearance by Michel Simon) are grotesques, but that is very much intentional.

A tale of light versus darkness, good versus evil, those darkly glowering faces provide counterpoint to the luminous face of Joan, shot with some of the most loving close-ups ever committed to film.

Played by Renée Maria Falconetti in only her second (and final) film role, it’s a justly celebrated performance of such emotional intensity and passionate commitment that it led to an urban myth the actress ended her days in an insane asylum convinced she was Joan. It’s an astonishing performance in any equally astonishing film.

2. Andrei Rublev (1966, Andrei Tarkovsky)

The Russian writer Nikolai Gogol dreamed of creating in his art ‘a palace of colossal dimensions’, a masterpiece in which to house and display ‘the untold riches of the Russian soul’. A century later his compatriot Andrei Tarkovsky perhaps came closest to realising that lofty ambition in his cinematic tour de force Andrei Rublev.

Charting the life of the 15th century icon painter through a turbulent period of Russian history, Tarkovsky’s depiction of the Russian soul proved too raw however for the Soviet authorities, who denied the film a domestic release until its success at Cannes eventually forced their hand. Since then the film has become widely acknowledged as one of the crowning achievements of Russian and world cinema.

Despite its title, the film is less a biographical portrait of the great iconographer (tellingly we never once see Rublev painting) and more a portrayal of the epoch in which he lived.

Following a prologue depiction of a hot air balloon ride off the roof of a church, the film is divided into seven chapters covering the years 1400-1424, each section built around a spectacular set piece – including the pagan ceremonies of St John’s Night, a Russian re-enactment of Christ’s crucifixion, a Mongol raid and sack of Vladimir, and culminating with a scene where Tarkovsky manages to make the casting of a bronze bell into one of the most dramatic and moving scenes in cinema history.

But it’s other, quieter scenes that have just as much effect: rainfall upon a field, the movement of paint through a stream, a horse rolling on the ground by a riverside – the seemingly mundane transformed into the epitome of poetic lyricism.

Those images, often presented in exquisite long takes and accompanied by Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov’s ethereal score, make Andrei Rublev a thing of rare beauty, but that does not mean Tarkovsky shies away from depicting the savagery of the time. Artisans have their eyes gouged out and molten lead is poured down one unfortunate man’s throat in just two of the many horrific scenes that permeate the picture.

So when the film finally bursts into colour in an epilogue montage of Rublev’s paintings, it seems to ask how such serenely beautiful art emerged from such a horror-stricken age. Taken as a whole, Tarkovsky’s film casts a similarly spellbinding effect. A masterpiece in every sense of the word.

1. Marketa Lazarová (1967, František Vláčil)

An adaptation of Vladislav Vančura’s avant-garde novel of the same name, Vláčil’s historical epic deals primarily with the doomed love affair between the eponymous Marketa Lazarová and Mikolaš Kozlik of the rival Lazar and Kozlik brigand clans in 13th century Bohemia. Voted the best Czech film of all time by a survey of the country’s critics in 1998, the film stands as one of the greatest – and certainly most convincing – cinematic portrayals ever given of the medieval epoch.

The world of Marketa Lazarová is one we are not so much invited as immediately thrust into, enveloping the viewer with an intensity that can be almost overwhelming. That effect is partly down to the style of the film – with its vertiginous dislocations in time and space, dreamlike sequences and almost complete abandonment of expositional material – but also due to its extraordinary sense of historical veracity.

Describing most period films as merely contemporary people dressed up in costumes, Vláčil ensured that charge could never be levelled against his own picture by relocating his cast to the depths of the Šumava Forest for a two year period of preparation where they were put to constructing the various sets with traditional implements, living in period clothes and speaking in the dialects of the time.

As a result, there’s a palpable lived-in quality to the film and the acting feels less like performance and more as though the actors are literally embodying their respective roles.

With scenes depicting wild pagan rites, incest, rape and numerous other brutal acts of violence, it could easily have become exploitation fare in the hands of a lesser artist, but such is our immersion in Vláčil’s painstakingly recreated world that it never feels in any way sensational.

By filtering our viewpoint almost entirely through the eyes, thoughts and feelings of the characters, the film allows us to inhabit a world where we take as perfectly natural that a family should believe they are descended from werewolves, a father avert a curse by dismembering his son’s arm, or the heroine fall in love with her rapist.

Admittedly a difficult work (not so much to watch as to follow and it may take more than one viewing to piece together the film’s fractured plot and complicated character relationships), Marketa Lazarová nevertheless deserves to rank alongside the greatest masterpieces of 20th century cinema.

With astonishing visuals, an otherworldly score by Zdeněk Liška and uniformly excellent performances (particularly Magda Vášáryová as Marketa and Josef Kemr as the lupine Old Kozlik), it’s an incredible piece of filmmaking matched only by Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev in its intermingling of brutal violence with ravishing beauty.

Author Bio: Gordon Knox is a writer and journalist from Edinburgh. He has a particular interest in Eastern European and Japanese cinema from the 1960s and 70s, as well as the films of Werner Herzog, Andrei Tarkovsky, Béla Tarr and František Vláčil.