11. Melancholia (Lars Von Trier, 2011)

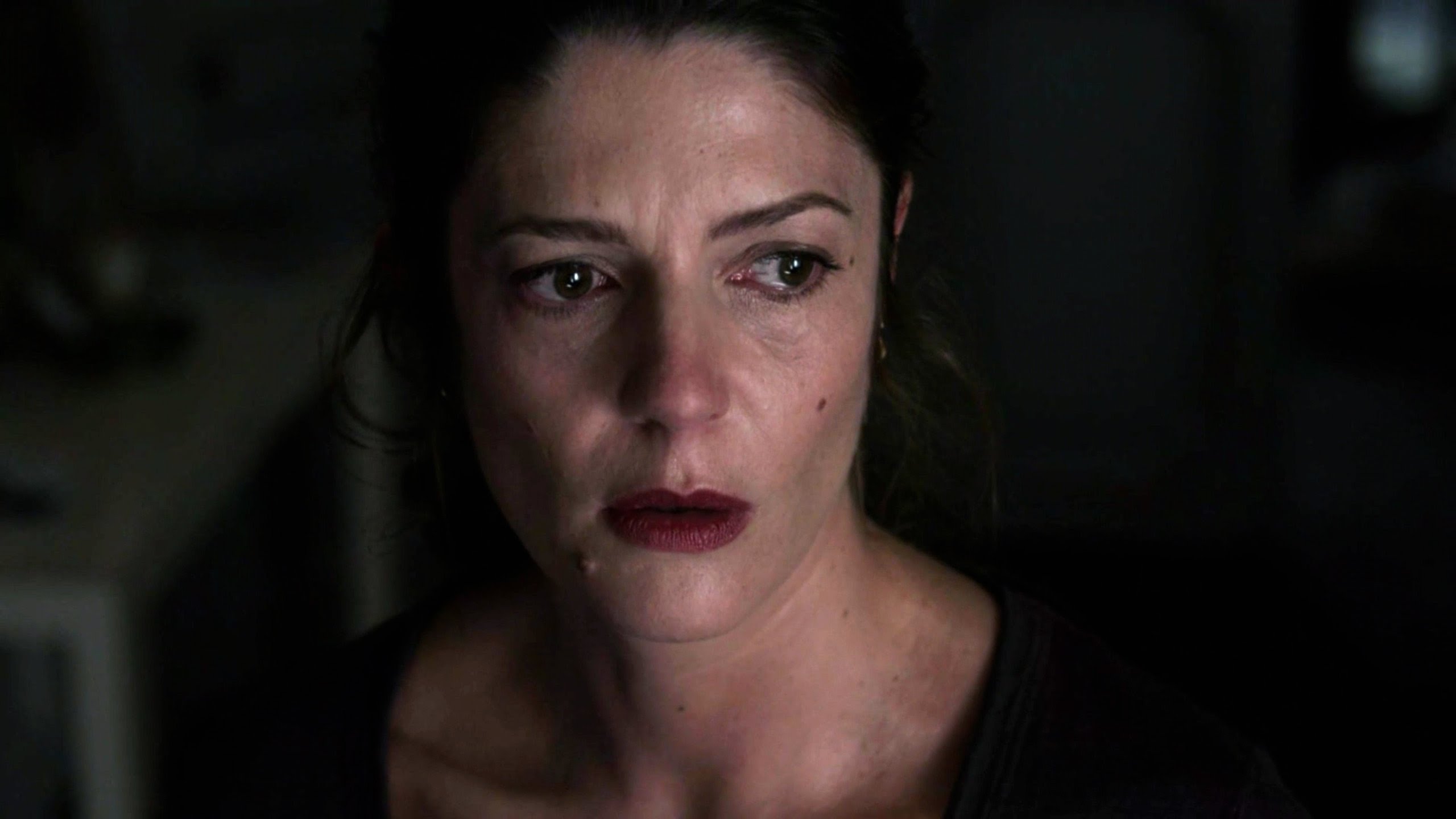

Melancholia temporarily assuaged the feeling that Von Trier is nothing more than arthouse cinema’s very own shock-jock. It is the second part in Von Trier’s Depression Trilogy, and by far the least overtly shocking of the three films (the last being Nymphomaniac). Melancholia is also more obviously about depression than the other films in the trilogy: while explicitly a story about the end of the world, it is obvious that this is figured as a metaphor for terminal weltschmerz.

The film is rigorously planned out as a map of the human psyche, with various characters standing in for archetypal moods and inclinations. Despite the dark, almost Strindbergian mood that undelies the film, it is perhaps Von Trier’s most unashamedly beautiful film: if any solace, or hope, is offered (Von Trier would probably blanch at the suggestion), then it is in the fact that such a beautiful film can be made about the darkest of moods.

12. Stranger by The Lake (Alain Guiraudie, 2013)

Alain Guiraudie is probably France’s most high-profile director of LGBT cinema, but it wasn’t really until Stranger By The Lake’s success at Cannes that his cinema reached the wide international audience it deserves.

The film is set on a secluded lake at the height of Summer, where gay men cruise for casual encounters. Franck is regular visitor, hooking up with a new lover each day, all the while becoming friendly with a somewhat morose and out-of-place older man, Henri, who has just been abandoned by his wife. Franck quickly falls for a newcomer, Michel, but rumors abound that Michel is responsible for a recent murder.

The murder causes police to pay frequent visits to the lake, disrupting the visitor’s idyllic retreat of casual sex and warm-hearted fraternity. As Franck’s desire for Michel becomes more and more intense, the film takes a deeply sad and tragic turn.

13. Irreversible (Gaspar Noe, 2002)

Irreversible is one of those films unfortunate enough to be remembered for just one scene. In some sense, many viewers are in fact thankful to have fair warning before watching the film and experiencing that scene – an excruciating eight-minute rape scene. One pities the viewer who watches this film without any idea of what they’ve let themselves in for.

Irreversible sparked a lot of debate about the ethics of cinema: where some argued that the film was exploitative trash, others argued that a treatment of such a serious topic should be as painful to watch as possible. Should we really “enjoy” a film that deals with something so horrible as rape? Should we leave the cinema feeling uplifted?

Answering with a firm negative, Noe made every effort to make his film as unpalatable as possible, right down to the sound design: the soundtrack incorporates a dissonant, low-frequency drone precisely engineered to provoke feelings of nausea. Irreversible is a radical experiment in extreme cinema, one that is understandably too much for many viewers, but which undoubtedly raises many serious questions about cinema’s relationship with violence.

14. Fat Girl (Catherine Breillat, 2001)

Anais and her older sister Elena spend their summer at a French seaside resort with their parents. Elena is a conventionally attractive girl who has plenty of experience with boys, though she is still a virgin. Anais is puzzled by her sister’s precious attachment to virginity, thinking that it is something that should be over and done with as soon as possible. Elena soon begins a flirtatious relationship with Fernando, a handsome Italian law student.

At night Anais witnesses Fernando’s attempt at deflowering Elena (the sisters share a bedroom), which culminates in some borderline coercive sexual activity. Anais’s experience colors her attitude to sex and love, leading to the film’s devastatingly ironic and thoroughly appalling denouement.

15. Bastards (Claire Denis, 2013)

Claire Denis has never been a director to shy away from dark subject matter. Throughout her career she has dealt in fearless fashion with some of the most pressing issues of the day.

Bastards, in some sense, has a much more limited scope than Denis’s more famous films. Marco is investigating the death of his brother-in-law, whose wife suspects was murdered by one of the family’s creditors. Marco moves in to an apartment below the suspected creditor, and quickly begins an affair with his wife. As Marco digs deeper, increasingly dark and disturbing details begin to emerge.

The film takes some elements from William Faulkner’s novel, Sanctuary. This was a book that Faulkner claimed was a penny-dreadful written in order to earn some quick money. Denis’s film is as short, sharp and brutal as Faulkner’s book, causing some critics to see it as a little shallow; for others, however, it is as a thoroughly captivating experiment in modern noir.

16. In My Skin (Marina De Van, 2002)

In My Skin is seen as a film of the New French Extremity movement. The films of this movement typically feature extreme violence and explicit, sometimes unsimulated, sex. In My Skin is also a very good example of Body Horror. Esther is outwardly a normal bourgeois French woman: great job, boyfriend and an active social life.

Things start to change after she injures her leg at a party. Because of her delayed recognition of her serious injury, the doctor asks Esther jokingly if she is sure her leg is really her own leg. This plays a part in instigating Esther’s heightened sense of body-consciousness, which finds expression in increasingly self-destructive acts of masochism.

17. A New Life (Philippe Grandrieux, 2002)

Philippe Grandrieux’s films are also usually placed within the New French Extremity movement, though his films have a very singular atmosphere that marks them out for special attention. Indeed, his films often cross over into the realm of video art: Grandrieux uses every tool at his disposal to create films that have a look and feel like no other. His work stands in a tradition of extreme experimenters like Terayama, Pasolini, Matsumoto and many more.

Like many proponents of extreme cinema, Grandrieux strongly divides opinion: La Vie Nouvelle was almost unanimously panned by critics upon release. Often the criticisms of this film, and Sombre before it, are moral in tone.

The films deal openly with themes of misogyny, misanthropy and self-destruction. Where some critics see Grandrieux self-indulgently reveling in corruption, others value his radical openness to the darker impulses of the human psyche, and his commitment to make cinema a tool adequate to expressing that darkness.

18. Lilya 4 Ever (Lukas Moodysson, 2002)

After the relatively feel-good Together, nobody could have expected that Lukas Moodysson’s next film would be one of the 21st century’s most relentlessly bleak films to date.

The film takes no time in setting its dark tone: we see a figure running against an industrial backdrop, to the crashing sound of Rammstein. Soon the camera closes in on Lilya, who has been badly beaten. The film then goes back to reveal Lilya’s past. Lilya lives in an unnamed post-Soviet city with her family. She is left under the care of her aunt, after her mother abandons her to move to America with her boyfriend.

As bad luck follows bad luck, Lilya is forced to work as a prostitute to make ends meet. The film’s broader social message becomes clearer when themes of sex slavery and human trafficking are introduced, to unforgettable and devastating effect.

19. Katalin Varga (Peter Strickland, 2009)

Peter Strickland has gained wide acclaim recently for his offbeat psychological horror fim, Berberian Sound Studio. Before that film, there was Katalin Varga, which Strickland filmed in Romania on a miniscule budget consisting of an inheritance from his uncle. As Berberian Sound Studio suggests, Strickland isn’t a typically British director—continental European influences dominate his aesthetic.

Indeed, Katalin Varga is somewhat Giallo-ish in theme, if not in exectution. When Katalin’s husband discovers that their son is not his, she embarks on a journey with her son to avenge the rapist who impregnated her eleven years ago. Like most revenge tales, things become far more complicated and messy than initially planned.

In tone, the film is often slow and contemplative, but Strickland already demonstrates an ability to build and maintain a sense of palpable dread. The mood is heightened by the film’s impeccable sound design, something which Strickland carried through to Berberian Sound Studio.

20. In Bruges (Martin McDonagh, 2008)

In Bruges may seem a little out of place in this list. It is primarily a comedy after all. But as comedies go, it is seriously dark. Indeed, close inspection reveals that the film can be mapped to Dante’s Inferno, with Colin Farrell as the poet-protagonist, and Brendan Gleeson as Virgil, his guide to the pits of hell.

Farrell plays Ray, a hitman who has accidentally shot and killed an altar boy in a botched hit. Ray and his more experienced partner Ken are told to hide out in Bruges while awaiting further instructions from their boss, Harry (played by Ralph Feinnes).

Ray finds it hard to cope with purgatorial boredom of the Belgian town, while Ken, the more cultured man, tries his best to take in all the cultural treasures the town has to offer. What follows is an often hilarious and often very sad film about the possibility of redemption.

Author Bio: Ciaran is originally from Dublin, Ireland, but currently lives in New York. He has passionate interest in European and Japanese cinema – the old stuff in particular. The directors who have left the deepest impression on him are Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer and Marco Ferreri.