Once upon a time there was a country, and that country made films. The films produced in the former Yugoslavia, both before and after its violent breakup in the 90s amidst escalating nationalist tensions from within and political stagnation and confusion across the rest of Europe and beyond, remain fascinating for anyone interested in the country or in films.

During the 60s, when the country was buoyed by an economic high, they even regular commercial and critical success; the country became a regular location for film scouts all across Hollywood due to its cheaper labour and wide geographic variety.

The country’s socialist dictator, Josip Broz Tito, more genial, liberal and significantly less brutal than his equivalents across the rest of Communist Eastern Europe himself was a great fan of films, and commissioned war films that promoted the actions of his Partisans against the Nazis in World War II.

Able to afford Western stars, these films, at various times, starred such names as Orson Welles, Yul Brynner, and even Richard Burton, and their budgets and scale easily matched and sometimes far surpassed their Hollywood equivalents.

Elsewhere, the roots of cinematic protest began to take charge. Inspired by the rule-breaking and anarchistic methods of the French New Wave, the Yugoslav Black Wave emerged alongside similar movements in Czechoslovakia and Poland. These directors, the most notable of which were Dušan Makavejev, Aleksander Petrović and Zelimir Zilnik, worked with low-budgets and little equipment to produce brave, inventive guerrilla films that even in a comparatively liberal communist country often fell afoul of the censors.

Despite the best efforts of the authorities, their influence lived on and found good ground in the following generation, which also produced Yugoslavia’s most internationally acclaimed and arguably most controversial director, Emir Kusturica. One of the few to win not one but two Palme D’or’s at Cannes, his films remain wildly inventive formally whilst often very tricky to navigate thematically.

The arrival of the wars and the breakup of Yugoslavia severely damaged the country’s filmmaking capabilities. Despite that, the directors, actors, and crews all soldiered on.

After the war in Bosnia finished in 1995, the film industry began its slow recovery. The authoritarian control of supposedly democratic Serbia and Croatia meant that both produced more than their share of horrible nationalist films that promoted ethnic violence, but nevertheless, good, nuanced films slipped through, and a new generation of filmmakers began to find their feet.

In Bosnia, ravaged by war more than any other nation, the recovery took slower, but its post-war films have arguably been the strongest; in 2001, No Man’s Land by Bosnian Danis Tanovic became the first film from the region, both before and post-breakup, to win the Oscar for Best Foreign Film.

Although there are now a multitude of separate film industries across what was once the former Yugoslavia, with the war a very recent, very lived memory for many filmmakers, that has not stopped collaboration. The once multiethnic identity of being a Yugoslav has not subsided onscreen, and it is not uncommon to see actors portraying different identities onscreen: a Bosnian being a Serb, a Croatian being a Bosnian, and so on. The war is an unsurprisingly common theme in modern post-Yugoslav cinema, but it is a very fertile one.

This list, is by no means definitive, for Yugoslav cinema is too rich and varied for that. It is rather, a primer for those unfamiliar with the region, the best bits from each era and each generation. May the next one be every bit as good as those before!

1. Man is Not a Bird (1965)

Amongst the most acclaimed of the ’60s Black Wave directors was Dušan Makavejev. Man is Not a Bird, his first feature, is a wonderful example of the style and grittiness that the Black Wave liked to employ. Mixing documentary elements, the assosciative editing pioneered by avant-garde filmmakers, and a traditional romance brings great fruit to bear for Makavejev.

Broadly, we follow the lives of two adulterous couples in a Yugoslav mining town in Eastern Serbia. Broadly, because Makavejev seems quite disinterested in their lives, prefering instead to take detours into the town, regaling us with scenes depicting the masses watching a hypnotist perform, an orchestra play, and a circus.

Deconstructing the way in which human beings builds roles for themselves and for others, the film critiques the blind faith of the Communist masses, but also questions much of the behaviour at the very root of human experience. Although Makavejev would refine and perfect the techniques he used in Man is Not a Bird to full effect over his next few films, his feature debut still represents his most anarchichal, rough, and free-spirited film.

2. I Even Met Happy Gypsies (1967)

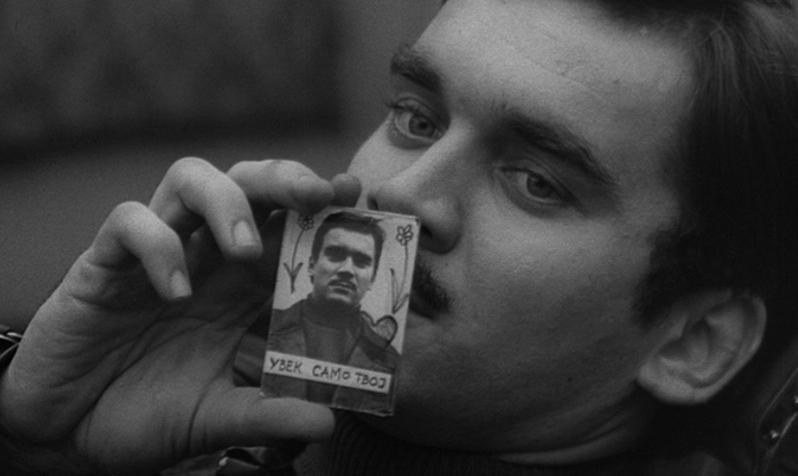

Almost 50 years since its release, and I Even Met Happy Gypsies, still rumbles with immediacy and energy. It is initially a very confusing film, dropping the viewer right into a world of Roma interfighting and shady business dealings on the muddy, ugly and unending plains of Vojvodina, the agricultural heartland of Yugoslavia in northern Serbia.

The characters introduced are sometimes hard to follow, and director Aleksander Petrović, a leading light of the Black Wave, refuses to explain the story to us, instead preferring to capture events unfold with an almost documentary realism.

The shock of the film may be lost on viewers today – such a purposely ugly film went completely against the grain of Communist propaganda which tended to portray Yugoslavia as a shining happy place full of happy Yugoslavs – but the film’s depictions of the underclass, the poverty-stricken bare bones existence of the Roma people still has value today, in a world which seems increasingly content to stamp out the voice of the downtrodden.

I Even Met Happy Gyspies has no happy Gypsies in it, just a collection of poor, depressed people, doing their best to survive and being exploited by criminals and mafiosos from within their own groups.

3. Innocence Unprotected (1968)

How does one explain Innocence Unprotected? In 1942, under the Nazis occupation of Yugoslavia, Dragoljub Aleksić, a Serbian acrobat and strongman, decided to write, direct, star, and produce a film, which he called Innocence Unprotected, the first Serbian talkie. Although it was made without the permission of the Nazis, the Partizan liberators didn’t like it much either as it represented an achievement they didn’t have much to do with, and repressed the film after the war.

20 years later, Makavejev came across the original film and was inspired to make his own. The entirety of the surviving original is shown here – and it is incidentally, a hilariously over-the-top and incompetent melodrama that would make Tommy Wisseau proud – yet it represents just one aspect of the deeply compelling and fascinating film that Makavejev made out of it.

Using the original footage as a springboard, Makavejev brings together the surviving actors, including Aleksić, to craft a film that’s about the blurred lines between fact and fiction; again he criticises the Communist government for their distortion of history in creating a new and unified Yugoslavia that was intended to be free from ethnic rivalries.

The film is also a character study of Aleksić, an exceptionally talented strongman capable of pulling off some incredible stunts (although filmmaking isn’t one of them), who also comes across as a born showman in his rather high self-regard, a man who loves creating myths and stories that view him in a heroic light – in much the same way Tito did. Ultimately, Innocence Unprotected remains one of the freshest, funniest, and deepest works of not just Yugoslav New Wave cinema, but cinema at all.

4. Who’s That Singing Over There? (1980)

Who’s That Singing Over There? is widely regarded as one of the greatest comedies in Yugoslavia, as well as one of the most subversive and intelligent. Scripted by Dušan Kovacević and directed by Slobodan Šijan (the duo followed up the success of this film with the equally famed and successful The Marathon Family), Who’s That Singing Over There follows a group of mismatched travellers journeying on a bus to Belgrade on the eve of the Second World War.

The cast of characters are broad, but each one represents a particular aspect of Yugoslav life. The young couple from the village (Slavko Štimac and Neda Arnerić), the latter keen to see life and the world outside of her house, the former a bit hapless and naive, an awkward lover and more interested in stuffing himself than in his wife’s happiness.

The smug, charming singer (Dragan Nikolić at his smarmiest) who is convinced of his abilities to seduce any woman. The bureaucratic busybody (Danilo Stojković), who moans about Yugoslav inefficiency and openly welcomes the forthcoming German invasion, hoping it will bring law and order to a chaotic land. The hapless, accident-prone hunter (Taško Načić) who gets kicked off the bus and somehow manages to keep pace with it on foot.

Towering above them all is the bus conductor (Pavle Vujisić), an authority figure so inept and inconsistent it’s a miracle the bus gets anywhere at all. Kovacević, a famed Serbian playwright before moving into filmmaking has produced many fine comedies, but have been as sharp, pointed, and gloriously ironic as this one. A deserved classic.

5. Balkan Express (1983)

An endearing wartime adventure film about a group of low-rent thieves and conmen who find themselves caught up in the middle of the Nazi invasion of Yugoslavia, struggling to decide whether to fight or to fly. They don’t really ‘choose’ in the end, becoming heroes by accident rather than design.

Directed by Branko Baletić, Balkan Express features an array of excellent comedic performances from a superb Yugo-cast. Dragan Nikolić, here at the pinnacle of his dashing, rapscallion star-power leads the way, but he’s ably supported by Bora Todorović and Tanja Bošović.

Set mostly in the undulating plains and endless vistas of northern Yugoslavia, Balkan Express centres itself around some recurring themes of Yugoslav cinema – its lovable rogues becoming heroes of the resistance more by accident rather than pure communist ideological fervour would be repeated in Emir Kusturica’s Underground, and its willingness to poke fun at even the darkest aspects of Yugoslavian history is a recurring happenstance across many Yugoslav films; the biggest laugh in Balkan Express coming in its most downbeat, depressing scene.

6. Balkan Spy (1984)

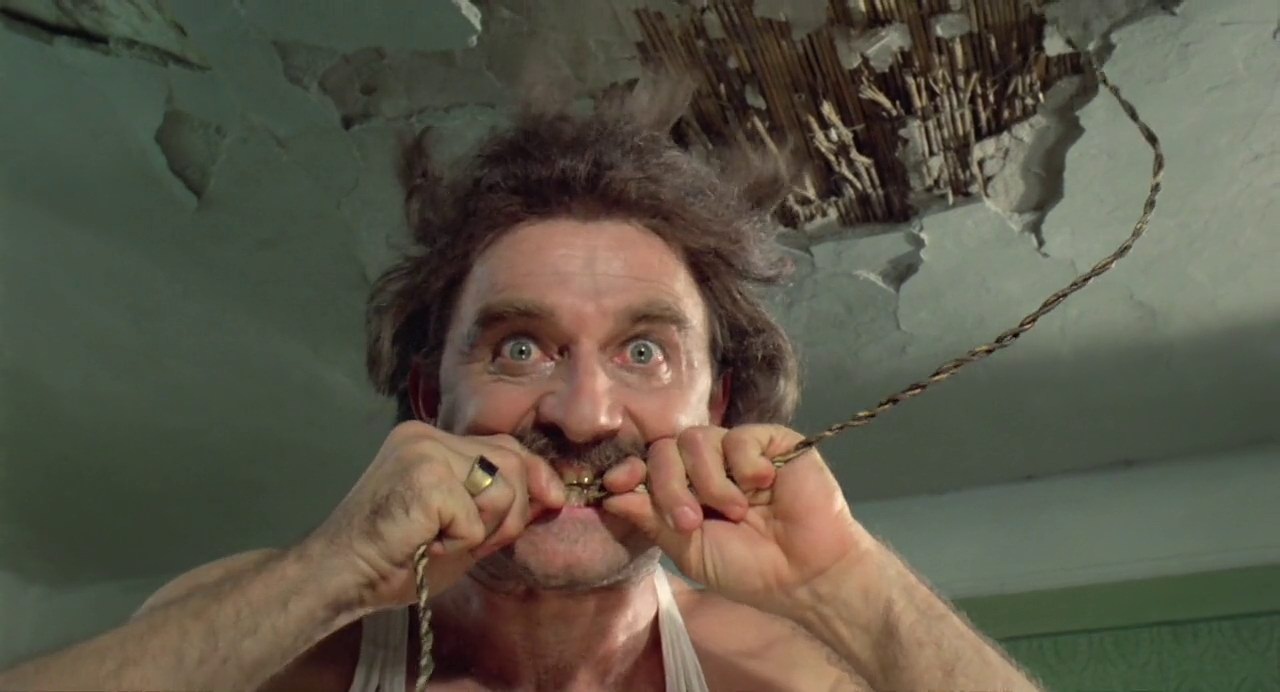

Even in a comparitively liberal communist state, surveillance by secret police was still a daily occurrence for most Yugoslavs. Although the UDBA would never acheive the notoriety of some of its fellow organisations like the Stasi, it was still a dangerous toy to play with for any potentially dissident civilian. Enter Balkan Spy, directed Bota Nikolić and Dušan Kovacević in his first directorial role, a hilarious spoof of the paranoia inculculated by state security.

A former dissident, Ilija (Danilo Stojković) becomes fearful that his new tenant, Petar (Bora Todorovic), just back from Paris with plans to open a tailor shop in Belgrade, is actually a foreign spy, and sets about conducting his own spying operations on the man so as not to fall afoul of the UDBA should his tenant be caught conspiring.

Satirising and poking great fun at secret police tactics as well the paranoia inculculated by communism, Balkan Spy was a great success at the time of its release, and is still relevant today; recent research has suggested that freedom of speech and media in the Balkans today is even lower than it was in the mid-90s when the war was at its peak, and the current government in Serbia led by Aleksander Vucić for example, is not above sending thugs to break up opposition meetings.

The film’s enduring appeal is also helped by Stojković’s, one of Yugoslavia’s most recognisable actors, whose small pudgy stature and paternalistic eyes made him ideal for playing fussy, pedantic bores who would tire other people out with their neuroses and finickiness.