7. When Father Was Away on Business (1985)

The first of two Palme D’or winners for Emir Kusturica came in 1985 with When Father Was Away on Business. Kusturica’s early career was marked by a series of fantastic coming-of-age films that combined the best of the bittersweet comic ironies featured in the films of the Black Wave with the cinematic grace and fluidity of the big-hitting European giants of arthouse cinemas at the time – Fellini, Bergman, Tarkovsky and the like.

Amidst the Tito-Stalin split in 1948 and the heightened political tensions amongst loyal Communists (“I’d rather eat Russian shit than American cake” one character shouts), Malik’s father Meša (Miki Manojlović) complains gently about the mood of anti-Stalinism. Unfortunately, his brother-in-law, a loyal bureaucrat, has a bone to pick with Meša, and upon hearing of this transgression sends him to prison.

This sends the family on a trip through Yugoslavia, moving from place to place trying to escape the shadow of ideological repression – at one point the boy makes friends with a Russian émigré girl (whose family have likely suffered the same repression purely by virtue of their origin) in the film’s most sweetest, most heartbreaking sequence.

Sprinkled with the influence of magical realism, on what was only his second feature film Kusturica crafts perhaps the greatest single film in Yugoslav history, a film bursting with life, energy, emotions on all ends of the spectrum. One of the greatest films of our times.

8. Tito and Me (1992)

Made in 1991-2, as the war in Croatia and Bosnia began to rage, veteran Serb director Goran Marković could have easily made a film that laid all the problems of Titoist Yugoslavia at the dictator’s feet, coupled with the nationalist sentiment that so easily surged in Serbia at the time.

Instead, he opted to produce one of the most intelligent and well thought-out films of the war, a rare voice of calm and criticism in a time of mindless violence. Tito and Me chronicles a boy’s idolisation of Josip Broz Tito in the 1950s as a way of distancing himself from arguments and frustrations at home, and also his eventual disappointment with the reality of Tito himself.

Criticising the cult of personality that Tito built around himself, the film would have been unthinkable barely a decade before. That it manages a complex and nuanced response to the legacy of Titoism without resorting to nationalist sentiments – the film is wholeheartedly Yugoslav – whilst also being wonderfully funny and charming thanks to smooth cinematography and excellent performances is testament to Marković’s skills as a director.

9. Underground (1995)

Underground was Kusturica’s second Palme D’or winner at Cannes, and is also his most controversial; at one point the debate that raged around the film frustrated Kusturica so much he claimed he would retire from filmmaking, although he went back on that promise. The mixture of allegory and metaphor in Underground is enough to fill an entire book, so to do it justice in just a few paragraphs is not easy. Over the course of the film’s near three-hour running time and 40-year narrative span it rarely lets up its unique artistic focus.

Starting in World War II, we meet two friends, Blacky (Lazar Ristovski) and Marko (Miki Manojlović), who both enrol in the Communist party and deal in black market trading. Amidst the chaos of the war, Blacky also finds time for a mistress, Natalija (Mirjana Joković), whose attentions he competes for with a German officer, going so far as to interrupt a theatrical performance she stars in to shoot the German and run away.

When Blacky is injured, he is sent to Marko’s underground cellar, with a host of other wartime refugees. However, with the end of the war Marko doesn’t open the cellar, instead telling its denizens that the war above ground is still raging and having them produce firearms for him, even going so far as to fake German bombings raids.

Meanwhile, above ground Marko becomes an important Communist dignitary and poet, praising Blacky’s exploits and turning him into a martyr for the Partisan cause, even marrying Natalija eventually. One day, amidst a drunken wedding the inhabitants escape their prison, and find a world that has changed unimaginably since they were sealed in.

With its exhausting running time and never-ending soundtrack of Balkan brass bands parping away in the background, Underground is a cinematic tour-de-force, showing Kusturica the stylist at the absolute pinnacle of his game. As Kusturica the thinker, the film functions on so many layers of metaphor and allegory that it’s occasionally almost impossible to know what is purely ironic and what is sincere.

The debate that has ranged around the film since its release has focused primarily on whether the film subtly promotes the Serbian nationalism that was the cause of much pain and suffering across Yugoslavia at the time, and there are legitimate concerns in this direction (for example, one of the production companies involved in funding Underground was RTS, the state-owned newstation that was responsible for justifying many of Slobodan Milošević’s nationalist policies).

Personally, I’ve always been of the opinion that the film is about propaganda rather being propaganda, and with this in mind, the film becomes an incredible treatise on the function and nature of competing histories and their political effects.

10. Pretty Village Pretty Flames (1996)

Another film that was accused by many critics of promoting nationalism on release, though again, critics have confused the depiction of something with the condoning of it. Instead, Pretty Village, Pretty Flames functions as a more sober and sombre reflection on the nature of nationalism and propaganda than the all-out energy of Underground.

Director/writer Srdjan Dragojević employs a complex flashback structure that allows him to flit between the childhood life of Milan (Dragan Bjelogrlić) and Halil (Nikola Pejakovć), a Serb and a Muslim who were best friends in peaceful times; Milan’s time in the Bosnian war, stuck in a tunnel under siege by his former friend; and his recuperation in a hospital with fellow surviving soldiers.

The group of soldiers stuck in that tunnel, able to hear the enemy but not see him (a wonderful device that demonstrates precisely how nationalist hatred often works), represent a near-perfect cross-section of the varying groups of Serbs caught up in the Bosnian war.

Some of them are willing, such as the old Yugoslav army captain Gvozden (Bata Zivojinović, a piece of clever casting as he was famed in the 60s and 70s for starring in many of the Partisan war films as a gung-ho action star), who still lives enamoured in the shadow of Titoism and believes he’s fighting for Yugoslavia; there is also Viljuška (Milorad Mandić), a Serbian ultranationalist Četnik who spews over-the-top maxims like “did you know the Serbs are the world’s oldest people?!”

Others are unwilling; Milan appears to have been forced into the war simply because it’s happening on his home turf, and a professor and a drug junkie have also been conscripted into the battle, taken from their homes, given guns, and told to fight. What results is a depressing, angry, brutal film that depicts the heavy effects of nationalism on the psychology of those forced to fight for it.

11. How the War Started on My Island (1997)

Of course, Serbia wasn’t the only country making films about the war. The others got their bit in too. One of Croatia’s finest post-independence films, this humorous satirical comedy direct by Vinko Brešan was based on a real-life event in Vis, the furthermost inhabited Croatian island on the Adriatic coast.

As Croatia declared independence, the Yugoslav army units stationed in barracks across the country refused to vacate the premises, leading to tense standoffs between townspeople and soldiers. In some cases, this sadly led to battles and bloodshed, but in others it was achieved peacefully, as it was in Vis.

The film attacks nationalistic ideas and ideological fervour with a gentle, ribbing bite, and is frequently deliriously funny, as well as well-acted and beautifully shot, although when it comes to the Croatian coast, you’d have to be a pretty incompetent filmmaker to make the area look ugly.

12. Beautiful People (1999)

Beautiful People is not technically an ex-Yugoslav film: though it is directed and written by a Bosnian, Jasmin Dizdar, it is set in England and predominantly features an English cast. Though its message is simple, the film is a humorous and typically Balkan tragicomic take on the lives of refugees in England during the Balkan wars.

Following a few interlinked stories, mostly about interaction between English and Yugoslav peoples, Beautiful People shows up the ignorant attitude of many people towards refugees for what it is, useless hate based on stupidity, a lesson that could well be learned today, but it attacks this with characteristic wit, warmth and smarts. It’s an underrated, hidden away little gem, featuring few recognisable actors both from the UK or from the former Yugoslavia, but is well worth tracking down.

13. No Man’s Land (2001)

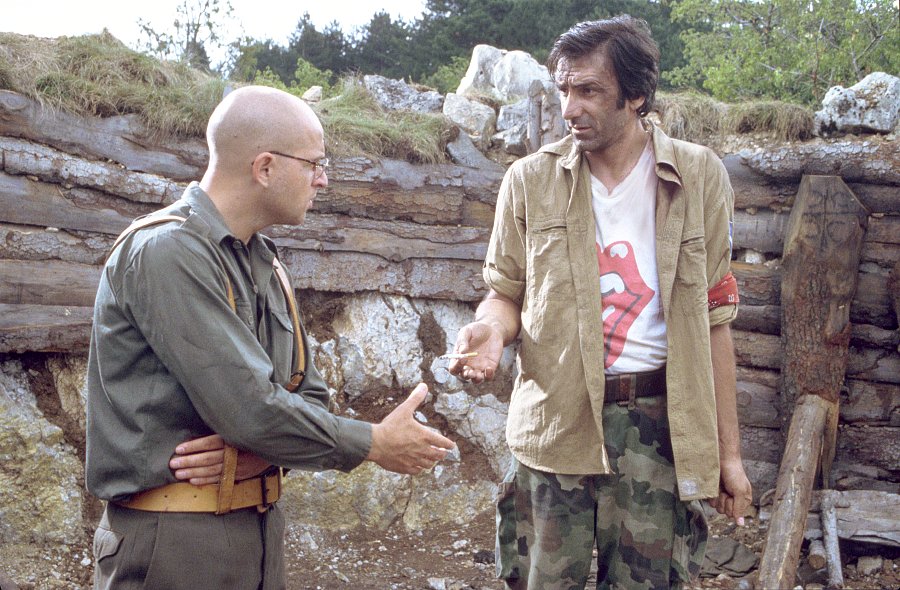

No Man’s Land stands in exalted company: it is the only film from the former Yugoslavia to have ever won the Best Foreign Film award at the Oscars. Only seven films in total have ever even been nominated, and all but No Man’s Land came before the war. It is a deserving winner however, telling the story of three men stuck in a trench somewhere between enemy lines.

Two are Bosnians, and one is stuck on a mine which will explode should he move. The other is a Serb. The three are supposed to hate each other, and for a long time they do. Yet as their arguments and bickering lead to nothing, they realise that the only way any of them can get out of this mess is to co-operate. They find even that a difficult task.

The UN and the media get involved, whipping up international sympathy for the plight of the three men and the trucks of reporters and blue helmets arrive. However, tensions still run riot, which the UN casually chooses to ignore. When everything inevitably ends in tragedy, the response of the UN general is simply to shrug his shoulders and say complain about the inevitability of it all.

No Man’s Land, directed by Danis Tanović, is representative of one of the recurring themes of postwar Bosnian cinema: the inability of the UN or the international community to do anything about the mindless bloodshed that was going on in the Balkans. The reaction from Bosnians has since been consistently sarcastic, biting, and rightfully angry, but also funny, humanistic and sharp, and few films are as consistent about it as No Man’s Land.