City-protagonist indicates a dominant narrative urban space which is more than just a virtual ambient containing the characters and facts. City-protagonist is the film’s principal narrative element and changing it will make the narration completely different if not meaningless. Indicating a location as one of the main characters of the narration may be a perfect way to remind the viewer of the importance of the narrative space in a cinematic work.

The films listed rely on the narrative space and its geographical and sociological specifications. The plots of these films are formed by numerous references to the spatial and temporal phase in which the story is taking place.

1. The Great Beauty (Paolo Sorrentino, 2013): Rome

The chosen locations of this film are all places found in Rome, except for one case where, for an obvious ironic reason, the spectator finds Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo) standing before a sinking ship in Grossetto, Tuscany for a brief scene that indicates hopelessness and depression.

The film displays the famous, archaeological sites of Rome. It examines a Neapolitan writer who, after having a huge success with his first book, has moved to Rome and since then hasn’t written another book, claiming he is too busy attending parties. The story criticizes the semi-intellectual society of Roman artists who are morally corrupted and depressed. The only characters who seem sensible are the dwarf journalist and the character of Romano (Carlo Verdone) who suffers from lack of self-confidence.

Sorrentino’s Rome is undoubtedly the main character of the story for it is beautiful, old and glorious. This city plays lots of architectural games: one can peer through a keyhole and see San Pietro church, precisely placed in that tiny keyhole.

One may also stride through a passage with false perspective where the dome at the end of the passage only seems to be big and only at the arrival one can actually realize the fact that the church is not that big, it only seems big as all the other measures are modified. It’s just a visual impression, a trick.

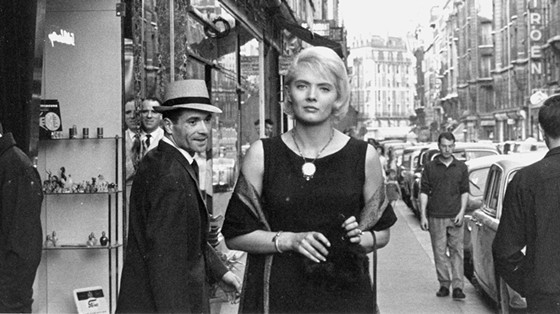

2. Cleo from 5 to 7 (Agnès Varda, 1962): Paris

The whole story is foreshadowed in the opening scene. A woman reads tarot cards for Cleo, warning her of a grave sickness and predicting the impending presence of Anton. Faced with a predetermined ending, Cleo from 5 to 7 is a film about interpretation.

The film is divided into chapters, each designating a character as the protagonist although Cleo, the film’s most important character, is the narrator of most chapters. Each chapter indicates a different time of the day.

The character’s reflection in mirrors and showcases is present during the entire film. While trying on new hats, Cleo is trying actually to wear other expressions, to forget about the sad prediction of the fortune teller. As the camera follows her wanderings in the hat shop, the reflection of the city is at all time looming above her, a reminder of sad reality. Initial exterior scenes are shot with Tele-lenses, spotlighting the dramatic elements within the real, almost documentary views of the city.

For Cleo, who insists that ugliness is death, the African masks in street showcases and frogs swallowed alive by a man on street are signs of death. The city is framed through various transportation mediums.

Cleo prefers taking a taxi, a more individualistic mode of transportation, while Anton invites her to take the bus and travel in a group. He is later going to take a train and then a boat to Algeria. He compares himself to the ugly frog and starts poetically idealizes the whole situation, even changing the name of the main character. He asks, “Why not using your real name, “Florence”, which reminds you of Italy instead of Cleo, “Cleopatra” which recalls the ancient Egypt and sphinx?

Varda’s Paris is a fortune teller, knows everything, contains everything and predicts the appearance of the characters before they actually show up. The news about French soldiers in Algeria is on the radio from the very beginning and is the fact that heralds the final exit of Anton, the most decisive character of the film, who finally converts Cleo’s point of view.

3. Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003): Tokyo

Tokyo in Lost in Translation is an exotically diverse urban city framed by two characters who do not belong to that location. This sense of alienation is emphasized by showing simple visual differences such as placing Bob (Bill Murray) together with short Japanese men in an elevator. He feels like a monster in Tokyo not only because of the fact that the shower is placed too low for his height and no one seems to speaks his language, but also because of the temporal (and emotional) distance between him and the place he calls home.

He calls his wife on the phone at night while relaxing in a bathtub, not remembering the simple fact that in the USA it’s daytime and the wife is busy preparing the children for school so that she is not capable of having a proper conversation with her husband. That is the same thing that the little old man in hospital’s waiting room tries to say with gestures. He draws a big circle in the air and asks Bob in Japanese: what time is it now in your country?

4. Manhattan (Woody Allen, 1979): New York

The characters of the film are reflecting the same theme as Isaac’s (Woody Allen) short story: people create problems, forcefully drive themselves into drama, to avoid thinking about other things.

Woody Allen believes New York to be a “knock out” city and shows it in black and white, choosing photographic compositions which represents an almost poetic visual interpretation of Manhattan. Eliminating color maps out the visual architectural forms and the characters are mostly shot within the surrounding elements, turning them into a moving element of the bigger architectural picture of this city. But black and white, conceptually indicates also “contradictory”.

At the beginning of the film, Isaac’s voice over reads out loud his various versions of the probable beginning of his short story about people in Manhattan and each version describes it as a different picture.

5. Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959): Hiroshima

In Resnais’s film, the bodies represent cities and geographical territories. The names of the protagonist are never revealed, they are known as He and She. He is a Japanese architect and She is a French actress who, through the whole story, compares her failed love relationship to the bombardment of Hiroshima. A relationship that goes wrong or simply ends is considered similar to a destroyed city.

The non-linear storyline of writer Marguerite Duras, combines flashbacks and fragments of a long conversation that the two characters are having during their last three days together.

This visual combination constructs an articulated architectural image, utilizing war as a conceptual reference. Something which ruins what has been constructed obviously indicates the memories and the future aspects the couple have constructed in past and compares what remains at the end of a relationship to a ruin, which in architecture is a nonexistent construction. It is not a building anymore, but a testament to the past existence of one.

6. What Time Is It Over There? (Tsai Mingliang, 2001): Taipei and Paris

Lee (Hsiao-kang), who sells watches on the streets, meets a young woman (Chen) briefly before she travels to paris. He changes all the clocks he sees in Taipei, setting them to Paris time.

What is indicated in the film is the fact that geographical distance is not merely a spatial distance but, most importantly, consists of a temporal gap. The fascinating notion that by mirroring the time of a distant city, the present location turns into the distant one. One can claim that the concept of city and urban architectural location in What Time is it Over There is a fluid, floating concept, very different from the normally articulated interpretations of architecture in films.

7. In Bruges (Martin McDonagh, 2008): Bruges

Bruges is an uncommon gift to a killer. A gang boss, Harry (Ralph Fiennes), who is obsessed with not hurting children plans to punish one of his hit men, Ray (Colin Farrell), who, while attempting to kill a priest, shot a little boy who was saying his prayers in the church.

Harry has chosen Bruges as the last city Ray is going to see, because Harry loves Bruges. But Ray hates Bruges, the best preserved medieval city in Europe, one which resembles the paintings of Brueghel. The fact that there’s a film crew present in the city during the same period justifies the exaggerated mass of unusual people in the most important scene of the film.

Harry chases Ray, who runs into the film crowd and by mistake shoots someone apparently dressed as a little boy. Ray tries to stop Harry from committing suicide and explains the fact that the one who has been just shot is a dwarf. Harry doesn’t budge and kills himself.

The initial geographical representations of the parts of city which are going to be passed over during the film, is achieved by having the two characters simply walking in those landscapes. In Bruges always returns to the locations so there’s not a tour of the city and there is no tourist approach towards Bruges.

It’s all about utilizing a city as a perfect symbol for embodying self-consciousness. Bruges of McDonagh represents a prewritten story; the character unwillingly takes part as details of a huge already designed mise-en-scène.

8. Roma (Federico Fellini, 1972): Rome

Fellini’s Rome is just as simple as the film’s first image of an old, ancient broken, falling apart stone. The voice-over narration that unites the scattered parts of the various stories of a neighborhood belongs to a young man, another traveler who arrives in Termini station in Rome, just a few days before the beginning of the second war world.

The picture Fellini gives of Rome is a satirical one. He, too, like Sorrentino in The Great Beauty, is criticizing the fact that Romans are still hanging on their past ancient glory. The difference is in Fellini’s sense of humor and the distance he maintains between the protagonist and his observation of the town.

This is unlike Sorrentino’s main character who is practically a part of what he’s mocking and criticizing. Jep finds Roman intellectual parties absurd, although he too is hosting these parties while Fellini’s protagonist is visibly different and distinguishable from his surrounding society.

9. In the City of Sylvia (José Luis Guerin, 2007): Strasbourg

The main character seems to be an author searching for his protagonist. From the very beginning of the film he does nothing but gaze at people, noting their figures and momentary gestures down in his notebook. The film is an almost two hour long observation.

At some point it seems as though he has found the Sylvia for whom he’s searching, but then something else, movements and sounds, lead him to another girl. At last he seemingly finds the “one” and starts following her, walking around the city, in alleys that she knows well, only to find ultimately that she is not the right girl. As soon as he starts speaking with the chosen girl, we realize that Sylvia is not an invented name, it is really the name of the girl he knew long ago and he has returned to Strasbourg to find her once again.

The opening scene takes place at night. Under the sliding lights of the passing cars are noted a few signs that tell the essential things about the character even if he doesn’t express himself verbally. He has a map of the city, so he’s a tourist and he’s temporarily living a little hotel.

Each individual sound effect is absorbed into the ambient sound of the city and is intently recorded. Hearing all these acoustic details is dramatically justified since the character is concentrated on sounds and urban landscapes, documenting every little detail that attracts his attention.

Primarily, Strasbourg seems like nowhere, a city placed in between. Initially in the hotel a girl knocks on the door and speaks in French while during the first external scene, a passersby distantly speaks in English, German,and Spanish and ultimately people with African traditional dresses pass by.

The same thing is repeated in all the other scenes. Apart from the fact that the main language of the city is French, there is no indication concerning the name of the city. It’s anonymous, mysterious and its presence is dominant, the city is Sylvia herself.

10. People on Sunday (Curt and Robert Siodmak, 1930): Berlin

The film claims to be created without professional actors, telling the stories of five characters: a model, a taxi driver, a vine taster, a film extra and the one who works in a record shop during a weekend in Berlin.

The film created in a documentary style, but having Billy Wilder as the screenwriter, the story is concentrated on the characters: a close shot of a tap not being closed completely is used to describe a character who is presumably a perfectionist and can’t stand causality. The film is silent, so in the aforementioned example a sonorous reference has been employed to develop a character without actually letting the spectator hear the sound of water drops.

The temporal element of the story is the weekend, when people can go to cinema, picnic, or do any other activity but their regular job. All the primary information about the professions of the protagonists after the introduction scene will be put aside since they’re not doing their jobs during the film. Instead, they’re on their own time and representing the Berlin of 1930 and its various entertainment possibilities.