7. The Great Train Robbery (1903, Edwin S. Porter)

When moving pictures were first invented, the films produced were nothing more than parlor tricks meant to grab the eye of the audience. It didn’t take audiences long before they started demanding stories out of these films, like they could get from the stage and literature. The Great Train Robbery was at the time the closest film had ever come to a story.

Viewers watched as a group of cowboys set up and executed a train heist, tying up the keeper of a station, jumping on board, and stealing the safe. We continue to watch as the bandits try desperately to hang on to their loot, avoid the law, and get away.

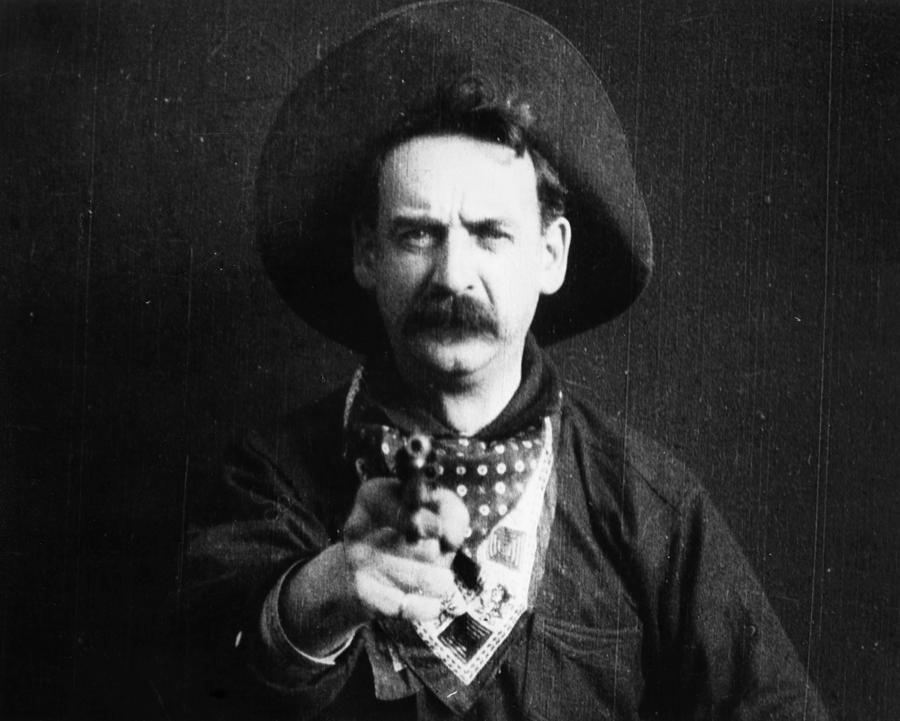

The innovations here are so numerous, and by today so obvious, that many wouldn’t even notice them. The film contains the first examples of the camera tracking to follow the characters. It shows early examples of the cross-cutting that Griffith would later perfect. Some of the prints were even colorized in the dance sequence, with each frame painstakingly hand painted.

And to good effect!—the shakiness of the color and imperfect film make the lively dance hall even livelier. The film even breaks the fourth wall, with one of the bandits firing at the complicit audience. It is arguable that film wouldn’t have outgrown its simplicity without this landmark short.

6. City Lights (1931, Charlie Chaplin)

Charlie Chaplin was indisputably the world’s first global movie star. He would travel to China and be instantly recognized. Everyone on the planet in the 1930s knew his unmistakable Tramp costume, with his short moustache, bowler hat, overly baggy pants and jacket, clown shoes, and awkward gait. Photos seen of Charlie without the hat and ‘stache are almost unrecognizable. He was deservedly the global icon of the silent era.

City Lights is arguably his greatest silent film. Audiences had seen The Tramp seventy times before, in short films, find himself in awkward social situations. But it wasn’t until he started doing the full-length features that his comedy began to evolve.

City Lights is an adorable film revolving around Charlie trying to earn some cash to help a pretty blind girl pay her rent. He tries to win some money in a boxing contest to hilarious effect. He eventually gets the money from a wealthy friend, but the cops think he stole it, and so he gets arrested. Later, penniless, he meets the girl again, and the love still blossoms.

Rather than simple Vaudevillian slapstick, Chaplin’s later films show bigger subject matter in his comedy, with City Lights, and the talkies Modern Times and Great Dictator examples of that. Lights could well be considered the first romantic-comedy, with works like The Graduate or Annie Hall serving as later expansions of the genre.

5. The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928, Carl Theodor Dreyer)

There’s the famous line from the film Sunset Blvd. that goes “All right, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up.” The line really ought to have been “All right, Mr. Dreyer…” for The Passion of Joan of Arc features some of the greatest uses of the close-up not just during the silent era, but in all of film history.

Maria Falconetti’s performance as Jeanne d’Arc is truly breathtaking. Every emotion—her fear, fatigue, anxiety, lamentation, and moments of hope—are perfectly struck. And it’s because of Dreyer’s genius idea to capture them all in close up that make them so astoundingly beautiful.

For much of the early days of cinema, films were shot from a medium length. The general idea coming from the world of theatre, at least initially, was to place the camera in the best seat in the house—middle seat, three or so rows back—and shoot everything from there, never moving it. It took filmmakers time to understand the promiscuity of the camera: it could go wherever you wanted to put in.

Close-ups had been used before Passion. The ending to Great Train Robbery was shot with a medium close-up. But the visceral impact of these close ups, Joan’s tears flowing larger than life, her distraught eyes the size of the Moon, bring Falconetti’s performance, and the whole film, to its legendary status.

4. Man with a Movie Camera (1929, Dziga Vertov)

The film itself tells us its point. “This film is an experiment in cinematic communication of real events without the help of intertitles, without the help of a story, without the help of theatre. This experimental work aims at creating a truly international language of cinema based on its absolute separation from the language of theatre and literature.” What the film sought to do was create a grammar of moving images.

As was discussed with Chien Andalou, striking imagery can certainly evoke emotion. Movie Camera shows up that the images don’t have to be surreal and horrific to be evocative. People doing their everyday things around the city of Moscow are also incredibly evocative. If shot correctly.

Vertov, by speeding up and slowing down the shots, by changing the distance of the camera, by playing around with editing, by tightening or loosening the composition of each frame, showed how a filmmaker can convey meaning, tempo and emotion through these technical aspects alone. Story is not necessary.

3. The Birth of a Nation (1915, DW Griffith)

Birth of a Nation is famous for its innovative editing. It is also infamous for its racist storyline. It’s hard to say which facet of the film is more historically important or significant.

Birth of a Nation centers around the civil war, and the wedge it drove between the North and South, and between individual families even. The film is nearly three hours long, and features battle scenes of epic proportions, especially for its day but by today’s standards as well.

There were many innovations in the film, but the major one that guarantees the film’s permanent place in history is the development and refinement of cross-cutting, which allows the filmmaker to show two scenes set in separate places as occurring at the same time.

Griffith cuts back and forth from the battlefield to the Cameron family home, where family members argue about the politics of the war. This editing technique allowed films to grow exponentially in their ability to tell stories of a grand scope. The technique has since developed to where Christopher Nolan can cut quickly not only between different locations, but different dream levels where time behaves differently.

The film’s infamy comes from its blatant racism, even for its day. The film imagines that after losing the Civil War, The South would be controlled by its former slaves.

We see black men (really white actors in blackface) shoeless and drunk on the floor of the U.S. Senate, among many other extremely offensive scenes. The history around the film is fascinating, involving many riots, the argued revitalization of the KKK, and Griffith’s following film Intolerance as something of a mea culpa.

The flawed masterpiece has been performing a historical dance with itself for 100 years now. Is its ground-breaking filmmaking, or outlandish racial overtones, the more significant feature of the film? Whichever trait wins the day, know that both are immensely important in film history.

2. Metropolis (1927, Fritz Lang)

Another over-two-and-a-half-hour epic of groundbreaking proportion, Metropolis extended the reach of German Expressionism, developed the department of special effects, and cemented science fiction among the most important story genres in the cinema.

Adapted from Thea von Harbou’s novel, by Harbou, Metropolis tells of a large underground city Marxistly divided between its workers and its planners. When young love attempts to bridge the divide, revolution ensues, and the proletariat workers seek their savior from the bourgeoisie.

The film represents a singular example of a large political statement in the silent cinema. The film’s projections of how society might evolve, of how work can degrade the workers, of where new technologies can lead, ushered in a new brand of science fiction, or to use Robert Heinlein’s term, “speculative fiction.”

Great works of speculative fiction like 2001, Blade Runner, A Clockwork Orange, Star Wars, Star Trek, The Matrix, and many more wouldn’t exist if not for Metropolis. The image of the Maschinenmensch still transfixes viewers today.

The special effects in Metropolis are mind-blowing. The biggest revelation was its use of miniature models. You can’t build an entire city like New York in a studio, but you can certainly build a miniature version of it.

Just as revelatory was the use of mirrors Lang and company employed to portray the actors as being within the model. Film locations, icons and themes once thought impossibly to portray in front of a camera, were now right in front of us, thanks to Lang’s genius.

1.Battleship Potemkin (1925, Sergei Eisenstein)

Battleship Potemkin represents the amalgamation of most of these innovative techniques. For editing there’s Griffith-esque cross-cutting and Vertov’s techniques from Movie Camera applied to an action sequence. There’s partial colorization with a specific purpose. There’s political themes and a powerful story. There’s everything that modern sound-and-color, 1080p films could ever ask for.

Potemkin tells of a Russian ship which was host to a mutiny, which continued on the infamous Odessa Steps as the workers sought to rise up. Eisenstein being a patriot, his films always told of the glory of the Soviet Union, and Potemkin is imbued with all the passion of a patriot exuberantly proud of his nation’s history.

The ship flies the red flag, hand-painted in the frames, but with a stronger intent than Edwin Porter or Rupert Julian ever imagined. The red flag jumps from the screen, like the girl’s red dress in Schindler’s List.

Of course the biggest breakthrough was the editing, about which Eisenstein wrote several treatises on his theories of “montage.” Griffith’s editing was for the purpose of telling his story.

Vertov’s editing was closer to Eisenstein’s, obviously because they were compatriots of the same school of thought. But Vertov wasn’t as harsh or confrontational as Eisenstein. His edits were dialectic, meant to create something new that didn’t exist with the mere frames. He put this theory to work in the amazing Odessa Steps sequence.

The mob rushes up the steps, which are busy with pedestrians, and the ensuing chaos is made even more chaotic by Eisenstein’s furious edits between long shots of the entire scene, to a close up of a woman’s shattered glasses, or a baby carriage about to tumble.

What Eisenstein created was the action sequence, which is absolutely vital to any modern film. And with no CGI or swooping cranes, the sequence is as exciting and awe-inspiring as anything Michael Bay, Roland Emmerich or James Cameron can muster.

The Odessa Steps sequence has been referenced in countless works, such as The Untouchables, The Godfather, and Brazil. But more importantly, Eisenstein’s editing techniques have been used in any film made since that features any type of action sequence at all.

Eisenstein brought editing up from an invisible technical requirement of film to a true art form distinct from all other media of art, and brought it to a level to which every following film editor would aspire.

Author Bio: Dylan Rambow studied film and journalism at Northern Illinois University. You can read his other film reviews at dylanonmovies.blogspot.com.