7. A Man Escaped (Robert Bresson, 1956)

Robert Bresson may be one of the directors who theorized more about cinema and its techniques. One of his main subjects was sound as an expressive tool. He saw sounds as a parallel image, so when the sound was too powerful to replace the image, the attention then must be centered on that sound.

He believed that you can “neutralize” the image for those cases, making a descriptive frame with not a lot of interesting information. This can force the audience to pay attention to the sound and create a stronger image in their head.

6. Rumble Fish (Francis Ford Coppola, 1983)

There is always an important difference between sound design and a good use of soundtrack. A film with a straight and boring sound strategy could use a beautiful score, or vice versa. “Rumble Fish” is another great sound experiment by Coppola where this difference is harder to tell. Coppola wanted time and clocks to be key concepts for the film, so his plan was to produce an experimental score to achieve this. For his clock-rhythm experience, he decided to ask a professional drummer with no experience in film, Stewart Copeland from The Police.

Coppola and Copeland were willing to explore outside their fields, mixing sound design and musical composition as one. Clocks, pool balls and steps are used as music and are directly mixed with Copeland’s composition. Copeland himself recorded some of the street sounds used in “Rumble Fish” and mixed them together with his musical compositions. The film didn’t receive the success that Coppola expected, but in the last several years won a new status in great part because of this conception of sound.

5. Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979)

Tarkovsky stated that in a perfect sound design, we mustn’t be able to recognize the difference between music and noises. “Stalker” was his most extreme case for this theory, making his composer create most of the sounds for the film, including some of the film noises performed on a synthesizer. He also wanted to mix Western and Eastern music for the score. Performing Western tunes on Oriental instruments and vice versa, Tarkovsky had the idea that both worlds could coexist, but might not be able to understand each other.

One of the iconic scenes with these ideas is the very first scene of the film where we see a couple in a room. In the director’s frozen shot style, we hear a lot of industrial noises without a clear precedence. The next scene shows a character in the middle of an industrial landscape and we hear the same sound, but with a more coherent image. All this playing creates an uncertain psychological atmosphere for the audience, and these kinds of experiments are all around in “Stalker”.

4. Tabu (Miguel Gomes, 2012)

In the last few years, there has been a new interest from different directors to recreate or to take heavy influence from silent cinema. Some films like “The Artist” (Michel Hazanavicius, 2011) try to imitate silent cinema codes, while others like Miguel Gomes’ “Tabu” try to establish a fluid dialogue between those codes and our modern codes. The pluri-narrative of the film, the way the characters move, and the cinematography reflect this dialectic struggle.

But, like in most Gomes’ films, the sound is maybe the wildest and most experimental element. As we saw in “Blow Out” or “Berberian Sound Studio”, most of the sound in film is duplicated, created or dramatized at the sound studio. But what can happen when the reference is silent cinema? Gomes plays with this challenge through the entire film.

We see a fountain with water, but we don’t hear the water move; instead we can hear trees on the back of the screen. To hear the forest heavily inside a room and having a quiet one in a forest scene, all of these mixing devices are made to give a hint of the fiction of film sound.

3. No Country for Old Men (Coen Brothers, 2007)

The Coen Brothers are recognized for their way of distorting film genre categories. “No Country for Old Men” was noticeable because of its new interpretation of western and thriller. In Sergio Leone’s classic or in John Ford films, the score always drives the tension. The game of looks between the characters before a killing spree is always intensified by music. Thus, the first film code the Coens subverted was music as an element of tension in “No Country for Old Men”.

There are few scenes featuring music, and in those scenes the mixing is kept to minimal volume, almost imperceptible for the audience. These pre-climax moments are not scored by whistles or violins like in western tradition, instead the cracks in the wood floor or fluorescents are the few elements we can hear before any shooting. The Coen Brothers worked with the same sound team used on “Barton Fink”, Skip Lievsay and Carter Burwell.

2. The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974)

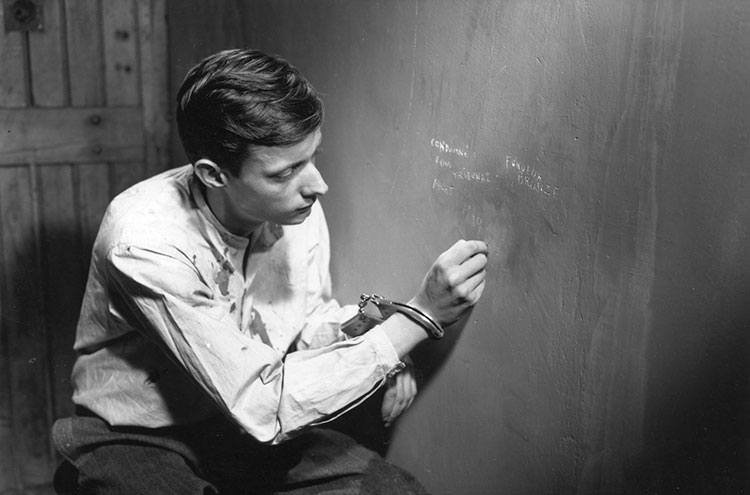

“The Conversation” can be probably named as the film with the biggest auto-reflection on sound use. Gene Hackman plays a paranoid spy recording a couple, and in the sound room he finds out that the couple will be murdered. Aside from the thriller elements, the film works as a big metaphor on sound and private/public spaces. Hackman records the couple in their intimacy walking around a park, and at the same time is totally frightened by the idea of someone interrupting his intimacy.

As we can see in his work on sound editing, we start to think about this work applied in the film we are seeing. Immediately we think that the audience is indeed spying on Hackman. “The Conversation” reveals sound devices and strips technical aspects of cinema like in “Blow Out”, but without directly talking about film. However, the work is the same, using manipulation, control and spying. This film is one of Coppola’s best.

1. M (Fritz Lang, 1931)

Most historians have recalled the first years of sound in cinema as slow. Many of the first films didn’t know how to use this new tool and filled the screen with endless dialogue. Many films started to look like recorded plays, and much of the language started to take a step back. Sound had many critics in its first steps, including the famous resistance of Charlie Chaplin to use it in “Modern Times” (1936). That is the reason why “M” can be seen as a film of the future.

Jacques Rivette said about “Viaggio in Italia” (Roberto Rosselini, 1954): “When Viaggio in Italia came out, the rest of the films aged 10 years,” and the same could be applied to “M”. But what it makes “M” a lesson about sound design? The great discovery made by Lang was silence. The thing the first sound films failed to see was that with sound silence came as well, and it is inside that game where sound can be a masterful tool.

The unsettling whistling of the killer in the film works because it enters in an almost empty background. You can hear Peter Lorre’s whistling, his steps, and the mumblings of the kids in total silence. With that game set, every time we hear the song we know danger is near.

Author Bio: Héctor Oyarzún is a film student in the Valparaíso University of Chile. Since he was a kid, his most important occupation is watching films. He also likes punk music and playing guitar.