7. Planeta Bur (1962)

When one of three Soviet rockets heading to Venus is destroyed by a meteor, the remaining cosmonauts and their robotic companion decide to continue their mission of exploration despite the inherent and obvious danger. Touching down on the planet they are greeted by killer plants, six foot Godzillas and a pterodactyl. And all of these after a deceptively academic tone was set by the opening disclaimer stating Venus ‘may not be exactly as it is shown in our film.’

Between this and the cosmic explorers’ cuddly android John blasting big band show tunes, it would be easy to dismiss Planeta Bur as frankly silly. And yet there’s something more to it, a certain early-Space Race charm and Soviet kitsch as these intergalactic emissaries casually discuss Konstantin Tsiolkovsky or the possibility of intelligent life having visited Earth. It might not be Solaris but its ebullience deserves plaudits.

8. These Are the Damned (1963)

Also known as simply The Damned, Joseph Losey’s sci-fi oddity is a weird farrago of disparate parts, never fully piecing together and yet culminating in a fascinatingly bleak finished product. The horror convention of placing someone in a dangerous and foreign place to be preyed upon plays out in the first act as a middle-aged American insurance executive visits an English seaside town only to fall victim to a local gang of rockers.

Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock is an obvious influence in what at first appears to be quite a predictable drama. That is until the incestuous desires, Cold War hysteria, inhumane science, beatnik artists and hopelessness emerge from the cracks within the structural hodgepodge of the script.

The characters represent diametrically opposed facets of society. The ultra conservatism of a British government scientist decrying the “senseless violence” of youth while conducting his own horrifically cruel experiments clashes with the brash rebelliousness and self-aware angst of alienated leather clad twenty-something motorcyclists.

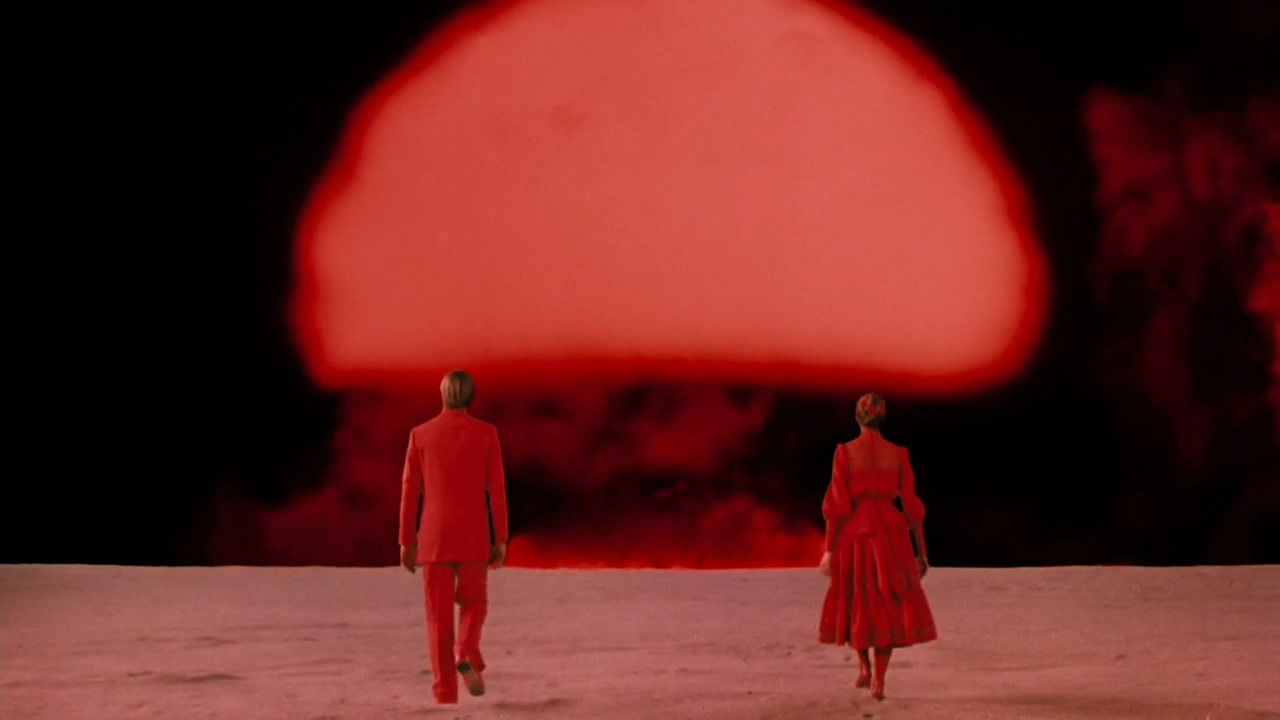

The subversion of genres and storylines will surely come as a surprise although it is certainly hinted to early on. The opening shots contrast the serenity and lazy Sunday vibes of coastal towns with grotesque and decaying sculptures that are explained soon after but not fully understood until the final sequences. The film’s horror is largely atmospheric and thematic; the greatest scare is drawn not from bumps in the night but a crushing sense of the inevitability of societal destruction.

9. Marooned (1969)

Arriving in cinemas just a year after Kubrick changed audiences’ perception of science fiction forever, it is understandable that Marooned has been condemned to being little more than a footnote in the genre’s history. However that of course does not make it justifiable. John Sturges’ film is a slow burning, tense drama that rewards viewers’ patience with dramatic set pieces delivered with measured brilliance from a cast including Gregory Peck and Gene Hackman.

Three astronauts have a serious problem when their return to Earth after five months in orbit is rendered impossible through mechanical failure. The film flicks between Houston, Cape Canaveral and the claustrophobia of their Command and Service Module, vividly imagining the possibilities of a rescue attempt decades before Ron Howard would do so and years before Apollo 13 launched.

In doing so it achieves a commendable blend of the procedural aspects of space travel and the more fantastical elements. By being respectful to the source material – a novel by aeronautics expert Martin Caidin – a sense of realism is achieved, lending gravitas to the more elegant cosmic sequences.

At times the ambition of these scenes extends beyond the capabilities of the visual effects, though the film’s receiving of an Academy Award in this field ought to reassure you this isn’t a frequent occurrence. Similarly some liberties are taken by the set and costume design departments but not to the extent that they lessen the storytelling.

When publicising Gravity Alfonso Cuarón admitted to watching Marooned ‘over and over as a kid’ and its effectiveness as a deeply human drama means it ought to receive much greater credit than it does.

10. Dark Star (1974)

The crew of the intergalactic scout ship Dark Star are not the brave or noble adventurers of 2001 or Interstellar. They’re simply blue collar guys operating heavy machinery. Their job involves cruising through space blowing up unstable planets so as to make the surrounding cosmic regions safer for future colonists. But mostly they sit around, smoke, listen to country rock, annoy each other and complain about the food. Their current mission has lasted over twenty years and it shows.

Originally a 45 minute student film its significance ought to be recognised if for nothing else than for those involved. Between them John Carpenter and Dan O’Bannon directed, wrote, produced, scored, edited and starred in Dark Star and the film is full of tiny indications of the talent, creativity and humour that would define both of their future careers.

It’s a laid back and bitingly funny parody of space exploration tropes featuring a beach-ball-with-claws pet alien, philosophical bombs capable of forming logical arguments and stubbornly sticking with them and four very bored men. Although made on a shoe string its effects and production values are exemplary and matched only by the intelligence of its cynical humour.

11. The Super Inframan (1976)

Between the Kung-fu, giant flying lizards, half-octopus humanoids, half-human beetles, mutant army, reptilian monsters disguised as mountains and death-rays-for-legs nuclear enhanced saviour of humanity, there’s not much that China’s first superhero film doesn’t have.

If Toho’s Monster Island hosted a rave in a cave, invited the Power Rangers and the Autobots who in turn bought all their friends and enemies, the end result couldn’t hold a candle to the utter insanity of even the first five minutes of The Super Inframan. Camp fun for kids at its very, very best.

12. Rabid (1977)

Amongst David Cronenberg’s storied career is the enormously misprized and unappreciated layered sci-fi body horror Canuxploitation piece Rabid. While recovering from emergency experimental plastic surgery after a near fatal motorcycle crash, Rose grows a phallic, scorpionic stinger in her armpit. She soon finds herself lusting for blood against her will and inadvertently spreading a highly contagious deadly disease as a late-seventies Typhoid Mary bringing ruination to Montreal.

An air of sleaze hangs over the film though never without reason. It needs to be said that this is in no way due to the finely drawn performance of ex-adult film star Marilyn Chambers in a role that highlights the disappointment of her failure to reinvent her career in the cinematic mainstream. Instead this derives primarily from an array of seedy, middle aged, secondary male characters.

Rose would normally want nothing to do with them but her illness urges her to seduce and graphically slaughter one after another. Along with the infection of a few rather more innocent victims, the virus soon spreads alarmingly rapidly across Canada.

Rabid doesn’t deserve to be compared with The Fly or Videodrome but rather is an example of the taut and highly atmospheric low-budget pieces of Cronenberg’s early career. It’s politics and satirical edge are more nuanced than is often acknowledged and it ought to be respected beyond its current status.

13. Altered States (1980)

Like its director Ken Russell’s career, Altered States is at its best when at its most insane. At times dragged down by pretentiously wearisome dialogue that eventually becomes a parody of itself, the film may test audience’s patience but repays all faith placed in it with a lamenting, hallucinatory and bizarre second half.

In his film debut William Hurt stars as Professor Edward Jessup, an academic obsessed with discovering the original state of human consciousness through a combination of mysticism, ill-advised experiments and no shortage of natural narcotics.

Although fundamentally an exercise in style over substance the brash and baroque psychedelic intensity is exhilarating, if at times unintelligible. It ultimately stands up as evidence that switching off and simply enjoying a film that is all surface needn’t mean watching something dull or unimaginative.