8. Antichrist

“She” is almost catatonic with grief over the death of their child. “He” takes it upon himself to heal her through therapy. When this does not work, they retreat to “Eden”, a cabin in the woods where She last felt happy. There Her condition deteriorates and He becomes growingly suspicious and less trusting of his wife.

Much has been made of the extreme violence She perpetrates in the film – and extreme it is – but often overlooked is the psychic violence He visits on Her. At every point he condescends her, undermines her feelings, telling her time and time again that her grief is wrong.

Antichrist is an absolutely bleak and nihilistic portrayal of grief, despair and bitterness. It contains images that are at once beautiful and horrific. In that cabin in the woods nature itself seems to be closing in on them. The atmosphere is one of oppressive and unrelenting doom. This is an unspeakably cruel film, and utterly mesmerising.

9. Peeping Tom

Mark Lewis is an introverted and reclusive young man whose demeanour betrays a secret, inner world. He is driven by his own internal demons to kill, and he uses his beloved video camera to document his victim’s terror at the moment of their deaths.

Mark belongs to a pantheon of tragic screen villains, such as Frankenstein’s monster and Norman Bates, who inspire sympathy from the viewer. By all outward appearances he is a kind, decent man, if not a little eccentric. He himself is aware of the horror of his compulsion, but is powerless to stop it. He does not want to kill, he simply must.

Peeping Tom is effective on its own as a stylish thriller, but by allowing the viewer insight into what drives his actions, he is afforded empathy and understanding, and this only adds to the horror of the proceedings. Everyone strives to be a little better, and Mark Lewis, monster that he is, is no different.

10. The Haunting

The troubled Eleanor, lost in life after the death of her invalid mother – whom she looked after for years – and unappreciated by her surviving family, joins a crew led by the charming Dr Markway on an expedition to the legendary Hill House in search of supernatural phenomenon.

A prologue explaining the long and troubled history of the Hill House explains that it was “born bad”, and the filmmakers effectively invoke this feeling. From the stark but sumptuous black and white photography, to the oppressive neo-gothic architecture and the skilful use of camera work to suggest the presence of evil, Hill House becomes a character unto itself, a malign and overpowering presence.

Eleanor is the archetypal outsider, out of step with life and those around her. Her journey to Hill House is one in search of a purpose and, though at first terrified by what she experiences there, she eventually comes to a belief that she has found a place she belongs and willingly succumbs to its machinations.

Ripples of the film’s influence can be felt today, and with good reason; The Haunting is a classic of horror cinema.

11. Audition

Takeshi Miike’s Audition is notorious for its scenes of extreme violence, but to reduce it to just another entry in the “torture porn” genre is entirely reductive of the film’s brilliance, and ignores a huge part of what makes it so effective.

Widower Shigeharu Aoyoma takes advantage of his job as a film producer and stages a fake audition to screen for potential wives. So taken is he with applicant

Asami Yamazaki that he becomes blind to all warning signs that she might not be quite what she seems, until it is too late.

Audition works not only as a mystery, a thriller and a hallucinatory nightmare, but also as a treatise on the sometimes problematic relationship between men and women. Shigeharu externalizes his own wants and needs so thoroughly onto Asami he ostensibly objectifies her and fails to see anything but what he wants to.

Asami is so insecure and affected by her troubled past she puts all her worth and hope for happiness in finding a man who will love her, and her alone, and on her own monstrous terms. They are a match made in hell. The results are horrifying.

12. Carnival of Souls

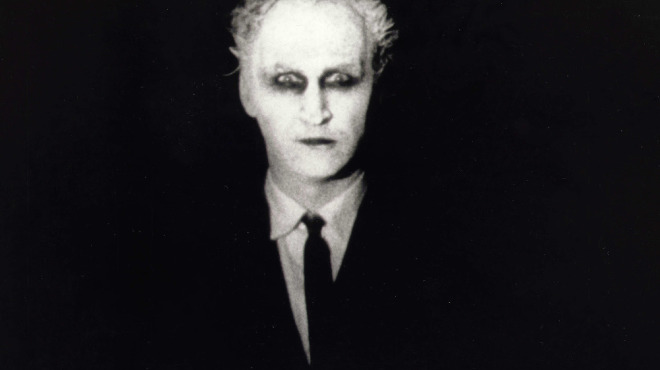

Mary Henry drags herself dazed from a river some time after the car she is in plummets into it from a bridge. Thereafter experiencing strange occurrences and plagued by visions of a ghastly, pale-faced man, Mary begins to question her sanity.

She is a self-professed loner, but as the terrors around her close in on her she finds herself afraid to be alone. She finds herself drawn to an old, abandoned carnival, and there she just might find company after all, just not the company she seeks…

Carnival of Souls was a little-seen, low budget production that has attained cult status over the years. It creates a strange, dream-like atmosphere with its spooky photography and off-kilter organ score. It is an odd, haunting film and, at times, genuinely chilling.

13. Eyes Without a Face

This macabre tale of Doctor Génessier’s attempts to repair his daughter Christiane’s horrific facial injuries via kidnapping unwilling transplant donors offers a more sombre and elegant take on the Hammer Horror films of the fifties Restrained for the most part, it is not without its shocks, including a grisly and protracted surgical sequence that is gruesome even by today’s standard.

Christiane injuries were sustained in an automobile accident, and she is encouraged to hide her disfiguration underneath a blank-faced mask. It is a testament to Edith Scob’s acting that she is able to convey such shame, self-loathing and increasing madness from beneath this featureless and creepy visage.

Whether Dr Génessier’s experimentations are indeed motivated by guilt, or whether this is merely a front for his scientific ambitions, the cold and efficient manner with which he is able to operate on and discard his victims is chilling. Aiding him in the procurement of these victims is his assistant Louise whose complicity, even though motivated by empathy, is just as alarming.

A tale about the horrific ease which people can dehumanise others, Eyes Without a Face makes for unsettling viewing.

14. Hour of the Wolf

Alma and Johann are vacationing on a remote island, where Johann is plagued by nightmare visions and is increasingly unable to sleep. Alma relays direct to the camera her account of his slide into madness and eventual surrender to the demons that plague him.

Bergman’s lone foray into horror territory is a gothic nightmare, brimming with a perverse sense of menace. The photography by long time collaborator Sven Nykvist is icy and foreboding, wringing chills from scenes set in oppressive, near darkness as well as bright, glaring daylight.

It is an elusive film – one deeply personal to Bergman – but whether read as a tale of long-repressed desire, the anxieties of the tortured artist, or something else entirely, it’s bold, almost profane imagery, enigmatic dialogue and haunting photography will not soon be forgotten.

15. Onibaba

In war-torn Japan, an elderly woman and her young daughter in law support themselves by murdering stray soldiers and trading their stolen belongings. A wedge is driven between them when the younger of the two begins an affair with a friend of her now deceased husband who has arrived home from the war, spurring the older woman’s jealousy. A chance encounter with a lone samurai wearing a demon mask provides the old woman a chance at retribution, but at a horrific cost.

A tale of jealousy, betrayal and selfishness, Onibaba explores the depths to which individuals will sink when confronted by harsh times and threatened with oblivion. The high-contrast black and white photography is absolutely striking and elicits a palpable sense of dread and despair. The endless fields of forever-windswept grass seem almost alive, and provide an evocatively hellish location for this tale of grim humanity, demons and the blurred line between.