24. Bug

“You have a centre, right?” Peter Evans tells Agnes White. “A place inside you that is just you, that hasn’t been spoiled… I think it’s really important to keep that space sacred. Sex and relationships cloud that space.”

When Agnes first meets Peter he is awkward, aloof and kind; everything her recently paroled ex husband Jerry is not. Fearing Jerry’s ire, and glad to have company in a life that has been empty since her child went missing years before, Agnes allows Peter to stay in her apartment where the two grow close. However, her lonely desperation blinds her to the fact that Peter’s eccentricities may have a deeper, more disturbing root. His slide into madness is inevitable, and she is taken down with him.

Bug is a story of shared delusion, a folie à deux. An electric blue nightmare, it is impeccably assembled and features breathtakingly intense performance from its leads. An excruciatingly heartbreaking scene late in the film reveals the full origin and extent of Agnes’s pain. There exists in her a vacuum – so easily filled by Peter’s lunacy – and she surrenders wholly to his paranoid logic in a psychotic rant of discovery. Agnes has lost her centre. Bug is utterly agonizing.

25. Les Diaboliques

Headmistress Christina is long suffering at the hands of her abusive husband, Michel. Together with his mistress Nicole, they plot his murder, which they will stage to look like an accident. They throw his corpse into the school pool, but when the body isn’t discovered as planned and appears to have gone missing, things take a strange turn.

The film plays out initially as a very Hitchcockian thriller (indeed, Hitchcock is said to have been beaten to the rights to the book by director Clouzot by mere hours), but the disappearance of the body takes it in an unexpected direction and adds a mysterious layer to the proceedings. The viewer is just as baffled as the two women. Christina, known for her weak temperament, is most affected by the bizarre twist. Her guilt and increasingly erratic behaviour threaten to give the game away.

The answers eventually come in the films dark and frightening climax, which contains one of the most thoroughly memorable images in horror cinema. Les Diaboliques is one of those films with a twist so famous that to not know it is truly an enviable position.

26. The Cabinet of Dr Caligari

What is there to say of Caligari that has not been said before? Watched, loved and endlessly dissected for nearly a century now, it is the seminal horror film. Its influence echoes today.

Doctor Caligari comes to town for the local fair boasting the spectacle of Cesare the Somnambulist, whom he claims sees the past and knows the future. Their arrival coincides with a string of murders. Suspicions fall on Caligari and Cesare when Cesare’s reply to an audience member who asks “How long will I live?” is “Until dawn”. The man is found stabbed to death the next day.

Caligari is worth recommending for its visuals alone. It creates a nightmare world of twisted architecture and painted on shadows. Not to be overlooked is riveting performance of Conrad Veidt as the enigmatic Cesare.

The film contains a twist at its end that throws another perspective over everything that came before. It is a classic case of the unreliable narrator, and posits the expressionistic design as a kind of psycho-space of madness. The film exudes a strange hypnotic power that has not dissipated with time.

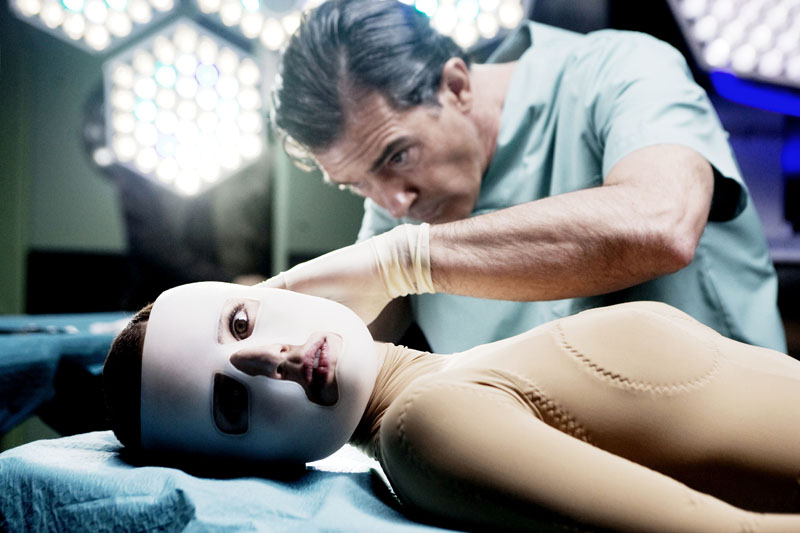

27. The Skin I Live In

Doctor Robert Ledgard has perfected a type of synthetic skin that is impervious to burns, which he hopes to use in facial transplants. With the assistance of his housekeeper Marilla, he keeps captive a mysterious young woman named Vera, who appears to be the subject of his experiments. Just who is Vera, and what is the full nature of her relationship with her captor?

Almodovar takes his penchant for melodrama, mischievous sexuality, playing with gender roles and plot twists and supplants them into a twisted display of lust, loss and revenge. There is obvious influence from “Eyes Without a Face”, both visually and thematically, but Almodovar takes those ideas and pushes them here to the extreme.

Antonio Banderas as Doctor Ledgard creates a character so dark and amoral it is near impossible to empathise with him even after learning the motivation for his perverse schemes. The nature of his experiments on Vera, and the full extent of his degradation, is truly appalling. This is a dark territory, but completely compelling.

28. Don’t Look Now

John and Laura Baxter are living in Venice where John is assisting in restoring an old church, both still grieving from the accidental drowning of their daughter sometime before. There they encounter a medium, who through premonition warns John of imminent danger. Before long, John begins to repeatedly see a small figured clad in a red coat, just like the one his daughter wore when she drowned…

John’s dismissal of the medium stems from his own scepticism, and he stubbornly refuses to heed any warning or pleas given to him by anyone. His own recalcitrance blinds him to the fact that he does not in fact need these warnings; the clues are already there for him to see. So sure of himself despite what is staring him in the face, John spells his own doom.

Nicolas Roeg’s gothic masterpiece is a restrained and hauntingly beautiful chiller. He extracts from the streets of Venice a cold and lingering sense of foreboding. His ability to suggest and imply menace, danger and the interconnectedness of events through the use of editing and colour is uncanny. The enigmatic, almost experimental style will hold viewers in thrall up to its final, unexpected conclusion.

29. The Orphanage

Laura moves into an orphanage with her adopted son Simón, where she herself was raised as an orphan. She plans to open the orphanage up as a home for sick and disabled children. Not long after moving in, Simón disappears and is never found.

Stricken with grief, and haunted by strange happenings, Laura begins to plunge into the ugly history of the orphanage – specifically the mystery of a deformed former resident named Tomás who drowned there years before. The revelations of past injustice she finds will lead her to the answers of what happened to her own son.

The Orphanage moves along at a measured pace that is careful to illustrate the humanity and grief of its lead, so that in her journey to uncover the mystery of he son’s disappearance the viewer is right along with her.

The film’s thick air of sorrow and loss has the effect of rendering the scarier moments all the more chilling by eliciting such empathy for Laura. The ending is devastating, and ambiguous, leaving the viewer with a lingering sense of uncertainty appropriate to a film about the unendurable loss of a child and its devastating consequences.

30. The Others

Grace Stewarts gives her new servants explicit instructions for looking after her children: each door in the house must be locked before opening another; the curtains must always remain drawn. Her children Anne and Nicholas are photosensitive. Light could kill them, she explains. Seemingly coinciding with the arrival of the servants, a series of strange events starts to occur, and Grace starts to believe her house may be haunted.

Nicole Kidman gives a solid performance as the uptight, overprotective Grace. Life has been hard since her husband died in battle, and so she loves them with a kind of stern frenzy. She is a wounded woman, but her harsh demeanour masks an inner turmoil. This is a story of loss, the fear of further loss and denial.

The Others is a hard film to speak about without revealing its secrets, suffice to say that it is a conventional haunted story that offers an unconventional twist in its tail. For this reason alone it is worth recommending, but the performances and style add another layer.

Author Bio: Paul William lives in rural Queensland, Australia. A former film student, he now works in a video shop and is an undergraduate in Journalism/Writing. He lives, breathes and eats cinema.