9. Lemonade Joe (1964). Dir. by Oldrich Lipsky

To Europeans, the classic American genre of Western has provided much fodder for zany and eccentric comedy. Jiri Trnka’s Song of the Prairie, Bruno Bozzetto’s West and Soda-the list can go on. The one that tops them all is this nutty and downright acidic number.

The titular hero is a clean-living gunslinger in a frontier town, who only drinks “Kolaloka” lemonade and is frequently confronted by whisky-chugging cowboys, while also struggling with affections for both a sultry bordello brunette and an angelic and blonde evangelist’s daughter. And-it’s a musical (with unforgettable numbers like “Whisky, My Joy” and “When the Smoke Thickens in the Bar, Do You See My Moist Lips?”)!

Still insanely popular in Czech Republic, its draw is the crazy style (the fight scenes are sped-up like in the silent film, and the bw stock is color-tinted). While beneath the frolics it actually carries a message of Government and Big Business going to bed together (with some religion, for good measure), it can also be enjoyed for what it is-an ivory-ticklin’ wagon of laughs.

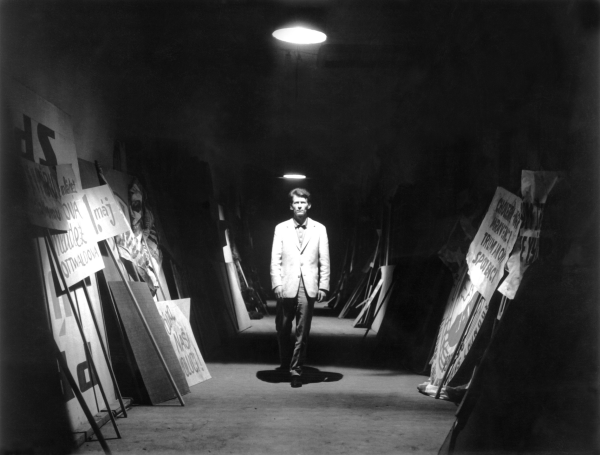

10. …and the Fifth Horseman is Fear (1965). Dir. by Zbynek Brynych

A day in the life of a Jewish doctor in the WWII Prague that turns into a noir. And an example how popular genre themes and stylistics can be used to tackle a darker and more serious material. The protagonist is called upon to treat a wounded resistance member. He then embarks on a nightmarish search for morphine.

The plot may sound socialist-realistic, yet the style is anything but. Brynych creates the occupied Prague that is closely related to the Vienna of the Third Man-an inhospitable, shadowy, and strange place. Sharp editing, harsh lighting, and hyper-acute camera angles enhance that atmosphere, as does the inspired musical score (jagged and nerve-filled piano music is mixed with “uplifting” brass band marches.

Music blaring everywhere from the loudspeakers, the city soon begins to feel like a concentration camp, and apartments and interiors-like cells. One striking locale replaces another-a room full of confiscated clocks ticking the life away, a storage of abandoned musical instruments, a nightclub where patrons seek escapism. All combine for an unsettling, but deeply rewarding experience.

11. Joseph Kilian (1965). Dir. by Pavel Juracek and Jan Schmidt

A 40 minute short that packs the power of the feature. Although he wrote in German, no writer has had more influence on Czech culture than Franz Kafka. And even though the directors tried to disavow the Kafkaesque ties, they are clearly there, making it, perhaps, the best Kafka adaptation ever.

In this film, a man searches Prague for his vague acquaintance Joseph Kilian (echoing Joseph K. of The Trial). He wanders from bureaucratic offices to a jazz concert, leases a cat for a day but is unable to return it due to red-tape nightmare, and continues on in his search in the maze of the city. This is a key film of the Czech New Wave, displaying all of its themes-stylistic virtuosity and novelty, critical and satirical take on the government.

The visuals are brilliant, right from the opening (a street crossing in the morning, where first a group of children cross one way, than a company of soldiers the other, and finally, a funeral procession). The changing of shots is masterful, and the cityscape is mesmerizing. Sound mixing is among the best ever, with even the silence being felt. An absurdist anecdote and an epic short.

12. Intimate Lighting (1965). Dir. by Ivan Passer

A film that strikes by refusing to be striking. Before having to flee to the West, Ivan Passer made a name for himself with this 72 minute bw gem. Its tight pace and compact style prevents from story being lost (a sin Passer is at times prone to committing). A professional concert cellist returns to his native small town with fiancée in tow. He reconnects with his former friend, who is now a local music teacher, moonlighting as performer at weddings, funerals, bar mitzvahs, etc.

Mild and cultured hijinks ensue, hued by the aura of nostalgia and feelings of life fleeting by. The film greatly benefits from simply fantastic and non-invasive cinematography by future Oscar nominee Miroslav Ondricek (who also made a name for himself in the West with Amadeus, Silkwood, Awakenings, Valmont, and other brilliantly shot films).

Here, the camera glides along with protagonists, affecting the overall mood. Passer manages to include many lengthy themes into the brisk running time-past vs. present, the role of music in life, and, indeed, life itself. The overall air of the film is wonderful, and it leaves a bittersweet and positive aftertaste.

13. Pearls of the Deep (1966). Dir. by Jiri Menzel, Jan Nemec, Evald Schorm, Vera Chytilova, and Jaromil Jires

One of the most important guiding lights of the New Wave was actually a writer. Bohumil Hrabal is not as known in the West as Kafka and Milan Kundera, but his surreal and innovative prose continues to be a source of inspiration. This omnibus film kicks the Czech New Wave into overdrive, by letting the recent film school graduates exercise complete creative control in bringing his stories to life.

I-Mr. Baltazar’s Death-Jiri Menzel’s true debut. The center of this segment is a real-life motorcycle race, observed by dissatisfied and nostalgic spectators. Humor turning dark. Menzel and Hrabal would go on collaborating to great acclaim (see #14).

II-The Impostors-possibly, the most lighthearted work of Jan Nemec. The biting satire and criticism present in his famous works, like A Report on Party and Its Guests, is barely hinted at in this simple tale of two old men in the hospital boasting of younger days.

III-The House of Joy-Evald Schorm. Much more colorful and playful than his later film and theatre masterpieces. Schorm hasn’t discovered his minimalist streak yet, and populates this engaging segment with many striking images-a slow-mo knife dance, sculptures of smiling crucified Jesuses along the highway, etc.

IV-The Restaurant the World-Vera Chytilova. The most surreal and opaque of the segments, with the line between dreams and real life all but erased.

V-Romance-Jaromil Jires. This tale of the love between a plumber and a gypsy girl is the most overtly political, questioning the Czech society mores.

It won’t do to list the visual joys of this endeavor. The main thing that drives it is the exuberant youth and giddy spirit of the makers, all of whom would go on to leave their mark on cinema.

14. Who Wants to Kill Jessie? (1966). Dir. by Vaclav Vorlicek

Much like Lemonade Joe, a crazy and crazy-fun genre satire. It should be noted that in Czechoslovakia comics were and remain very popular. This “science-fiction” screwball comedy directly borrows the aesthetics of the comic. The plot is launched when a husband/wife team of scientists invent a device that allows for a materialization of dreams.

Not satisfied with his joyless marriage, the husband dreams up his comic book object of affection-the beautiful and busty blonde Jessie (played by future Playmate Olga Schoberova). She is followed into the real world by her arch-enemies, the muscle-bound superman and the masked cowboy.

Watch out, Prague-there will be chases on the ground, underground, on the rooftops, and everywhere else. The axis of the story shifts when it becomes obvious that the wife wants not to contain her creation, but to eliminate her rival. What adds to hilarity is the comic book characters speaking with world balloons, which appear in real life, not to mention the hilarious sound effects. It’s probably the most colorful bw movie ever made.

15. Closely Watched Trains (1966). Dir. by Jiri Menzel

Charming and fast-paced tragicomedy that has to be one of the most successful feature debuts ever, picking up an Oscar and firmly establishing the director. Working closely with the original novel’s author Bohumil Hrabal (see #14), Menzel created a funny, sad, zany, absurd joy of a film.

The central hero, a lazy and careless young railroad worker in the waning days of WWII, desperately tries to lose his virginity, being almost driven to an early grave by his quest. His senior colleague helps him out by convincing a visiting actress (who moonlights as the Resistance messenger) to “take one for the team”.

Milos is thus cured of his depression and gains wider understanding of the world, partaking in the resistance-with tragic consequences. But the spirit of the film is anything but tragic. The camera literally flies and glides around this backward but crazy part of the world. Overall, it’s life-affirming and quirky, with many unforgettable details. A classic that deserves its status and is still watchable today. The close collaboration between Hrabal and Menzel pays off here, and ensure the film’s uniqueness.

16. Daisies (1966). Dir. by Vera Chytilova

All feminism should be this zany and joyous, as should anarchism (a point that many modern Fascist-leaning zealots of these movement would be wise to remember). Chytilova’s feminism is of explorative and non-judgmental kind, as evidenced by this, her best-known work.

Almost free-form in structure, it shows the frolics of two girls, the brunette Marie I and the blonde Marie II, who fight ennui with an all-out war on consumerist society, by doing as they please, wreaking havoc, and having a devil of a time at it.

Chytilova uses colors, sounds, and distorting optics to make this a must-experience circus act. And manages to present her ideas in a way that’s fun, funny, and highly original. Really a wonderfully insane kaleidoscope, the colors of which will stay with you for some time to come.

17. Miraculous Virgin (1966). Dir. by Stefan Uher

A Bunuel-worthy exploration of dreams and reality. This film is in the running for the most striking on this list. The story revolves around various artists falling in love with, and being inspired by, a beautiful girl (one of the additional reasons why Czech films are so watchable is due to female leads being very easy on the eye). Many themes are touched upon and questioned, mainly-what is real? The themes are illustrated with truly stunning locations and imagery, striking and symbolic.

The artist studios present many ideas for that imagery. Particularly memorable is Raven the sculptor, who makes death masks. Those poets and artists begin by desiring Anabela, and then usually transposing their desires into creations. The many questions it raises and the effortless way it switches between reality and imagination (in another memorable scene, the hero turns into a speaking lion) make this film worthy of rediscovery.