The cinema of former Czechoslovakia, as well as of current Czech Republic and Slovakia, is, perhaps, the richest and most visually striking of all Eastern Europe. Even though fun-as-bricks Commies have tried the best they could to stifle it, the zany and wonderful artistic visions found a way to reach the audience.

From the very beginning, the traditions of visual audacity reigned supreme, due in a large part to cultural traditions rich in imagery, imagination, symbolism, and surrealism. From medieval castles to Kafka, from puppet theatre to theatre of the absurd-all the filmmakers had to do is mine the fantastic and hilarious cultural gold.

It may be noticed that a large portion of the films in this list are from the 1960’s. It really was the true Golden era of Czechoslovakian cinema. The so-called “Czech New Wave” rivals the French one in freshness of ideas and unique works. Slovakian cinema too came into prominence at that time. Though a Communist country, Czechoslovakia espoused a more humane and breathable variety.

It all changed after 1968, when Soviet tanks rolled in and the so-called “socialism with a human face” was crushed. The best filmmakers either left for the West (Milos Forman, Ivan Passer), were condemned to periods of silence and inactivity (Jan Svankmajer, Jan Nemec), or had to find ways to retain their creativity while not crossing the multiple taboos that the oppressive regime forced upon them.

Of course, the restrictions largely went away with the fall of Communism, but now new realities set in-those of market economy, changing political and societal structure, and competition with the worst of the West. The fact that they continue making worthwhile and creative works is the best testament to their talent and spirit.

A note-in this list, Czech and Slovak filmmakers are presented jointly. In reality, their visions, though equally striking, do differ. Czechs urbanized fairly early, and benefitted from both the dark medieval city streets and the “wonders” of technological revolution. Whereas, even for the large parts of XXth century, Slovakia remained more rural.

While both Czech and Slovak cinemas benefit greatly from surrealism motifs, their respective surrealisms are often as different as the city is from the village, though taking away nothing from the visual feast.

1. Ecstasy (1933). Dir. by Gustav Machaty

The earliest Czech cinematic triumph was also, perhaps, the most scandalous. Both the Pope and Hitler denounced and banned it, as did most countries. Numerous heavily mutilated versions existed, and the star’s munitions tycoon husband have attempted to wipe it from the face of the Earth altogether. Its horrendous crime?

Light and tasteful erotica, and the heinous sin of showing female orgasm on screen. The 19-yeart old Hedy Kiesler used the notoriety of the film to escape her stifling marriage, flee to America, and land an MGM contract (as well as contribute to science by inventions in frequency hopping).

Lost in all the hype and scandals was the fact that Ecstasy is, in fact, a really good film that more than holds up today. It does so primarily on the strength of its visuals, which rival anything Jean Renoir made at the time.

The plot is rather melodramatic (a beautiful girl marries an old man who cannot satisfy her, leaves him, and finds happiness with another man), and dialogue is typical for early sound era. But the deft use of camera angles and lighting make every leaf and blade of grass sing from the screen. Several scenes are breathtaking-the loving shots of Eve bathing and then chasing the horse, the luminous light steaming from Adam’s cabin at night.

Without excessive moralization and relying purely on visuals, Machaty presents the conflict between natural and artificial and the need to live in harmony with one’s world. The shot structure is nearly flawless, with languid tracking shots followed by well-lit close-ups. The viewer looking for scandalous sleaze will be disappointed, but not the one who’s seeking great-looking cinema.

2. The King’s Baker and the Baker’s King (1952). Dir. by Martin Fric

A zany costume comedy that really deserves more of a cult status, denied to it by almost complete lack of international distribution. Welcome to the mysterious castle of Emperor Rudolph II. A devotee of the occult, he is plotting to bring Golem to life-while his conniving courtiers are equally busy plotting to overthrow him.

Help comes from an unlikely source-a royal baker, serving time in the dungeons for being wasteful with the king’s bread, and who happens to be Rudolph’s doppelganger. Switched identity hijinks ensue.

What makes this film such a delight is its magnificent look. XVI-XVII century castle and costumes are impeccably recreated on screen. As most of the film takes place in the castle, the magnificent set is given its due screen time. Lighting rivals the best of German Expressionism, and the color play is almost painterly.

It was partially filmed on captured Agfacolor color stock, and partially-on Eastman Color. The shadows are appropriately dark, and the bright colors shine. Add to it the hilarious plot and the awe-inspiring Golem, to complete the dazzling experience.

3. Old Czech Legends (1953). Dir. by Jiri Trnka

The live-action Czechoslovakian cinema of the early 50’s is largely forgettable. The Soviet “liberation” and the ensuing switch to Communism resulted in a large output of stilted and didactic “Socialist Realism” pictures. Fortunately, the same cannot be said about Czech animation, which successfully resisted both the Party line and Disney influences, and emerged as one of the most original artistic movements in Europe.

Jiri Trnka is a key figure of this movement. A painter and illustrator, he came to animation from theatre, and brought his unique artistic sensibility along. This is fourth stop-motion features (after the notable Czech Year, Princess Bayaya, and especially The Emperor’s Nightingale). Here Trnka considerably broadened the capabilities of puppet cinema.

The connected collection of tales from 1894 “Ancient Bohemian Legends” by Alois Jirasek, it is presented with complexity and virtuosity hitherto unseen in animation. The tales of kings and knights are given a world of their own, with intricately designed “sets” and “locations”. Here, the Heaven is in details-the character walking in snow leaves footprints, and his steps crunch appropriately. Lighting, camerawork, set design-all rival that of a live-action epic.

Camera pans, tilts, tracks, and spins. The crowd scenes are composed of individualized puppets. Trnka’s artistic background is further evidenced in fantastic background matte paintings. As for puppet design, he was able to further advance his technique of making puppets with purposely expressionless faces, so that different expressions can be shown by changes of camera angles and lighting. As a result, he succeeded in creating a paradox-a very real puppet world.

4. The Lion and the Song (1959). Dir. by Bretislav Pojar

Trnka’s best collaborator proves himself an artist in his own right with this beautiful short. When Trnka made his masterpieces, Pojar was the man responsible for being behind the camera and often doing the actual tedious stop-motion part. He would gain more fame later when he moved to the West, in all directing over 50 shorts in his long career.

This is his best early film. A wordless gem, it tells a story of the sombrero-wearing artist wandering the desert with his accordion and performing skillfully in front of the desert inhabitants. When confronted with a violent lion, he chooses to stay true to his art and his peaceful and loving nature. It’s easy to see how crucial Pojar was to Trnka as an animator-here, the stop-motion action is perfect and flawless.

The lighting, camerawork, and design are also on par with best in the medium, and the colors are vibrant and unforgettable. The human character design is very Trnka-influenced, but the animals are wholly original (especially the magnificent lion). In just over 15 minute, this striking and at times dark parable manages to touch several vital themes-being true to self, the immortality of true art. And does so with colors and puppets!

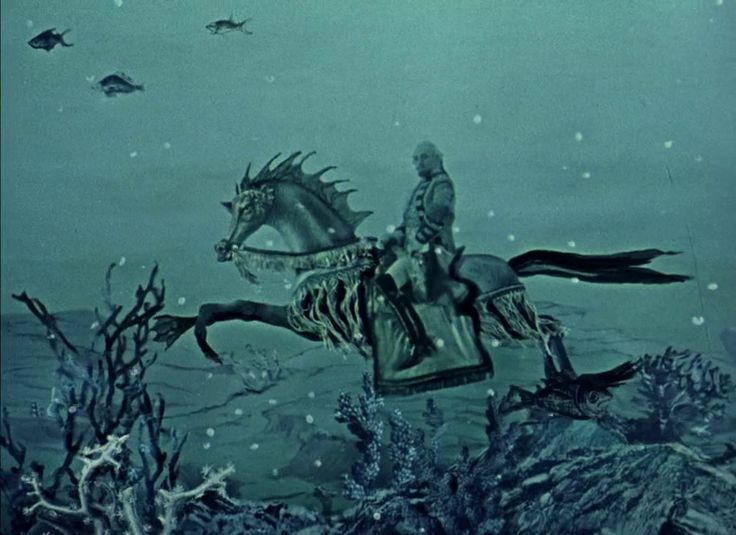

5. The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (1962). Dir. by Karel Zeman

Zeman was a medium all unto himself. His films broke and mixed the traditions of live action, animation, and painting, combining the best of them in zany and imaginative ways. His works influenced artists as diverse as Wes Anderson and Terry Gilliam (the latter openly acknowledging the fact, and paying homage in his own Munchausen film). The subject matter is perfect for Zeman-this is the best film about the creative liar and trickster.

In the film’s story, an astronaut lands on the moon and befriends the Baron. Together, they undertake countless adventures, travel the Seven Seas and then some, and become involved in a love triangle. Seemingly, the consummately romantic Baron has an edge over the too-pragmatic astronaut, but the latter learns and is able to grow as a person.

What makes this film so special is its one-of-a-kind look. Using the XIXth century illustrations by Gustave Dore and the stylistics of cinema pioneer Georges Melies, Zeman creates his own universe, where people and drawings, foregrounds and background, the real and dreamy-all intermix openly, and the distinction lines between them are erased. Many scenes are simply unforgettable-the ship pulled by Pegasuses, the journey in a belly of a fish.

Zeman further enhances the otherworldliness by the use of color-mostly sepia, but with flashes of brilliantly saturated colored stock that leave an indelible impression. The subject matter is perfectly suited for the style, and the viewer is left with newly found abilities to dream. For the moon belongs to lovers and dreamers only!

6. Frantisek Vlacil’s Medieval Trilogy: Devil’s Trap (1962)/Marketa Lazarova (1967)/Valley of the Bees (1967)

Nothing will prepare you for Vlacil’s incredible cinema. Having jump-started the New Wave with his 1960 The White Dove, he proceeded to make a truly epic trilogy of medieval-set films that routinely make the best of all time lists and remain ultra-watchable today. The settings of all three is the medieval Bohemia, but each presents a unique and fascinating experience.

Devil’s Trap (1962)

Here Vlacil more or less stretches his wings. The milieu is a land ruled over by an oppressive regent, who despises the few remaining free folk and sends a newly arrived Jesuit priest to stop the wise miller and his son, under the pretext that they might be cavorting with the devil. The questions of science vs. religion are thoroughly explored in the film’s relatively brief (compared with what’s to follow) time.

Valley of the Bees (1967)

Made before Marketa Lazarova, but released after, this is perhaps the most purely historical of the three films. Anticipating the Night Watch of the Game of Thrones, it tells the story of a young boy who is sent by his father to join the religious knight order, and what ensues when he temporarily breaks his vows.

As in the other two, the style here is beyond reproach, although not nearly as experimental as in Marketa Lazarova. Easily holds up against, for example, The Seventh Seal or The Virgin Spring, as a masterful and artistic exploration of the historical period and its spirit.

Marketa Lazarova (1967)

The most visually stunning film of this list, and one of the best ever made. Everything is impeccable about it. Vlacil came to cinema with an art school education, and brought with him the immense knowledge of what’s divinely beautiful. Here he manages to bring the medieval engravings to life in the most modern and technically accomplished way possible, thanks to his own herculean effort and that of his dedicated cast and crew.

The film’s basis is the eponymous novel by Vladislav Vancura, which takes place in unspecified medieval period and tells the story of two feuding clans. Basically, Iliad meets Romeo and Juliet, on the frozen plains and to the endless howls of the packs of wolves. Nature itself is a major protagonist here.

This film is that rarity of rarities-an avant-garde epic, possible only in Czechoslovakia of the 60’s, where an artist can bring his vision to screen without commercial restraints. The only ample points of comparison are Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev and Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai. All three are effervescent examples of a unique and striking artistic vision on a grand scale.

7. Something Different (1963). Dir. by Vera Chytilova

Recently deceased (2014) Vera Chytilova has made a number of films with striking form and content (see #16). This one, her feature debut, has firmly established her as a new artistic force to be reckoned with.

Freely jumping between live-action and documentary, it tells a story of two women. One (documentary) is a famous gymnast at the peak of her career, getting ready for her final competition. The other is a housewife with a toddler, going through the motions of her daily domestic routine.

The gymnast is under pressure from her team, particularly her coach, while the housewife has to deal with an indifferent spouse and the growing sense of ennui. Many of Chytilova’s works has been described as feminist, and this one is no exception. But her feminism is never as basic and ignorant as its modern espousers make it. Instead, she delves deep to present multiple sides of the inherent conflict and to question the sacred cows of the movement itself.

Here it’s illustrated by the fact that both women want something different than the lives they have-and then that “different” is shown, turning out to be nowhere near the expectations.

The style is particularly masterful-the live-action scenes of the housewife are presented in a low-key and documentary manner, while the footage of gymnast is expressive and bravura-with fluid camerawork and unique angles. The ease with which Chytilova shifts between live-action and documentary makes this film a masterpiece-and the best is yet to come.

8. A Jester’s Tale (1964). Dir. by Karel Zeman

Zeman gets another entry with yet another of his whimsical creations. Compared to Invention for Destruction (1958) and Baron Munchausen, this is a more live-action-leaning effort, though animation and puppetry are still sprinkled in. At heart an anti-war story, it chronicles the adventures of a young peasant couple and a musketeer during the Thirty Years War.

When their army is routed, they stumble upon rich clothing that they put on-only to be captured and mistaken for nobles. They are imprisoned at the castle of a local count, whose treatment of them varies as fortune of the war do. So, an escape is a must.

Thirty Years War is firmly rooted in Czech psyche (one-third of Czech population was lost), and the surroundings here are grim. Which just serves to underline the resilience of human spirit that finds ways to maintain itself even in duress. The zany chases and escapades, mistaken identities and Monty Python-like scenes-all combine to foster the spirit of hope. As usual with Zeman, the visual style is good enough to want to capture each frame and hang it on the wall.

Here he is inspired by the engravings of Matthaus Merian, with their clear and striking lines and shadow play. Throughout his long and rewarding career, Zeman served the artistic tradition well, while establishing one of his own that is seen in the works of some of the best filmmakers of today.