5. Robert Rodriguez

Robert Rodriguez’s career is almost inextricable from that of Quentin Tarantino’s: both filmmakers came up around the same time, both have similar interests and sensibilities, both became fast friends, and both have frequently worked with each other on various projects.

While Tarantino became a critical and Oscar darling, Rodriguez stayed a pulpier, wilder, Tex-Mex version of that same voice — not a bad thing either, because my what pulp he made. From the heady early days of his first film, El Mariachi (1993), which managed to make an action movie blast out of $7,000 south of the border, Rodriguez proved a propulsive, electric presence on the genre movie scene.

1996’s From Dusk til Dawn, starring and written by Tarantino, is one of the best horror films of the ‘90s; Desperado (1995), a remake-cum-sequel to his debut, is an amazing modern Western (its 2004 sequel, Once Upon a Time in Mexico, is none too shabby either); his 1994 cable TV movie Roadracers is an underseen gem; and he managed to surprise and make solid films aimed at the teen (The Faculty, 1998) and children’s (Spy Kids, 2001) audience. Heck, he even turned in the best installment of the misbegotten 1995 indie anthology Four Rooms.

Rodriguez hit his zenith in the mid-aughts, with his best films, the modern classic neo-noir comic book adaptation Sin City (2005) and Planet Terror, his arguably superior first half the Grindhouse project he made with Tarantino (2007.) Ironically, that’s where Rodriguez seemed to go wrong.

Whereas most of the filmmakers on this list went astray after a truly terrible film, a truly great film proved to be Rodriguez’s undoing, as if he kept chasing the dragon to increasingly mediocre results. When Grindhouse flopped, Tarantino licked his wounds, took stock of his career and went back to the Academy Awards. Rodriguez, on the other hand, looked at his Fulci-meets-Carpenter gorefest and decided that neo-exploitation was the way to go.

Machete (2010) and its sequel Machete Kills (2013), based on a faux-commercial from Grindhouse, took a one-joke premise and stretched it passed the breaking point, not helped by the clumsy insertion of social commentary from an arrested-adolescent director never known for it.

Rodriguez continued the bad trend of working with his kids to produce new children’s movies, something that has only paid off in painful dividends after the okay second Spy Kids (to wit: Spy Kids 3: Game Over [2003], The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl [2005], Shorts [2009], Spy Kids 4: All the Time in the World [2011]).

Worst of all was his despicable return to his greatest success: Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (2014), a shallow, witless, misogynistic and pointless successor to a truly great original. Rodriguez still wants to — sigh– make Machete Kills in Space, but there is hope that teaming up with James Cameron on Alita: Battle Angel will return him to his former awesomeness.

6. Dario Argento

Giallo icon Dario Argento was crowned the “Italian Hitchcock” upon the release of his first film, The Bird with the Crystal Plummage (1970) and with good reason — his debut was as clever, as twisty and as thrilling as Hitch at his finest.

Argento is second only to his contemporary and predecessor Mario Bava in bringing the giallo genre — named after pulp paperbacks with yellow covers that were inspired by German crime novels called “krimis” — to acclaimed international prominence.

His stylish, stylized tales of cosmopolitan murders were renowned throughout the world, in particularly his 1975 classic Deep Red, the tale of a jazz musician investigating the murder of a psychic. But it was his turn to the occult that really made Argento an icon: 1977’s sublime ballet-school witchcraft opus Suspiria permanently earned him a place on the list of scariest movies ever made list.

Argento’s ‘80’s output was not as well-received as his ‘70’s, but it’s certainly not disliked: Inferno (1980) his out-there, surreal, nearly narrative-free sequel to Suspiria (which may also be, arguably, his best feature), Tenebrae (1983) and Opera (1987), extravagant returns to giallo form, and Phenomena (1985), an audacious blend of Argento’s supernatural and more grounded serial killer sides, have all become cult favorites amongst horror aficionados everywhere.

In addition, the former film critic was also an acclaimed writer and producer, co-scripting Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time In The West and helping George Romero bring Dawn of the Dead to life.

It was in the ‘90s that Argento began a rapidly downhill fall from grace. With the sole exception of 1995’s underrated The Stendhal Syndrome, a rare foray outside of either giallo or supernatural territory, each Argento film from 1993’s Trauma on has seemed to be in a race to top the last one for being the filmmaker’s new nadir.

There was an awful slasher version of Phantom of the Opera (1998), a trio of increasingly dull gialli duds (Sleepless, 2001, Do You Like Hitchcock?, 2004 and The Card Player, 2005) and 2008’s Mother of Tears, the gory, witless, long-awaited (it wasn’t worth it) final installment of his “Three Mothers” trilogy (began with Suspiria and Inferno).

He hit his all-time low with Giallo, a dreary police procedural from 2010 that has nothing to do with the subgenre that made his name. Argento’s most recent feature, 2012’s Dracula 3D, is only a marginal improvement because it’s unintentionally funny whereas Giallo is just plain old interminably boring.

Argento’s output from the past two decades isn’t just bad, it isn’t just lacking in the budgets he once had, it feels like it was made by someone who just stopped caring. Even Argento’s most notable saving grace — the outre style that was his trademark — has dissipated, replaced by dull, functionary filmmaking compounded by cheap production values and poor scripts, devoid of any energy. It says something that Argento had to go to Kickstarter to raise funds for his next film, The Sandman, and even then could barely get fans to donate.

7. Brian De Palma

Brian De Palma has gone through various stages throughout his career, but his best known will always be his thriller phase. He began cinematic life as an American acolyte of the French New Wave, helming a variety of experimental, Godard-lite comedies (Greetings, The Wedding Party, Hi, Mom!, 1968-70), all of which starred a young, pre-fame Robert DeNiro, a phase which culminated in a poorly-received studio debut, the Tom Smothers vehicle Get To Know Your Rabbit (1972).

Following the dismissal of that Warner Bros features, DePalma changed gears, dropping the Jean-Luc and embracing his inner Hitchcock, and establishing the most fruitful era of his estimable career.

Harnessing and refining a stylistic panache begat from his experimental filmmaking, and employing a number of thematic fetishes that would come to define his career (including voyeurism and secret identities, both of which came from a youth spent spying on a cheating father), DePalma became the Film Brat generation’s answer to the Master of Suspense, both to the chagrin and delight of divided critics and cineastes everywhere.

It was his 1973 film Sisters, a diabolically twisted tale of murderous (formerly) conjoined twins, that put his name out there — but it was the troubled telekinetic teen instant classic Carrie (1976) that launched the director onto the A list…alongside such big names as Sissy Spacek, John Travolta and Stephen King, the then-unknown author on whose novel the film was based.

In between both films, DePalma helmed the opulent, cult-adored rock opera Phantom of the Paradise (1974) and Vertigo riff Obsession (1976); post-Carrie life found DePalma returning to psychic territory in The Fury (1978), sleazing up Psycho with his masterpiece Dressed To Kill (1980), putting sound recordist Travolta through the ringer in Blow Out (1981) and sexxing up his already-sexxed up thrills with the porn-themed Body Double (1984.)

De Palma’s later thrillers saw the filmmaker overlapping that phase of his career with the next: a turn towards “respectable” filmmaking, which mostly manifested in him adopting the gangster genre — his lurid remake of Scarface (1983) segueing into the less violent likes of The Untouchables (1987) and Carlito’s Way (1993.)

Though he misfired spectacularly with the Reaganomics satire Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), the director rebounded with Raising Cain (1992), dismissed initially as a self-parodic return to his genre roots, but really a delightfully trashy (and personal) embrace of them, and then his first summer blockbuster– the very good, franchise-establishing spy flick Mission: Impossible (1996), adapted from the TV series.

It was after this that DePalma began his stumble. Returning to thrillers failed to pay off in Snake Eyes (1997), despite that film’s epic opening tracking shot, Femme Fatale (2002), The Black Dahlia (2006) or Passion (2012), the latter two of which were the self-parodies Cain was slammed as being.

Having all the signifiers, but none of the thrills, DePalma was known for, they were poorly received box office duds. But none of those films were derided as bad as what are considered DePalma’s worst two movies: the saccharine, PG scifi drama Mission To Mars (2000) and a misguided return to experimental filmmaking with the didactic anti-Iraq War drama Redacted (2007.)

8. John Carpenter

One should never underestimate the towering contributions that John Carpenter has made to genre cinema. Horror, scifi, action — Carpenter has made iconic films in each genre, and often more than once each. His third film, Halloween (1978) is considered one of the scariest films of all time, was the most profitable indie film ever made (until The Blair Witch Project came along two decades later), and is credited with giving birth to an entire subgenre of film (even if there are a few lesser known titles that beat it to the punch.)

Initially dismissed at the time of its premiere, The Thing (1982) has become a classic in its own right, Carpenter’s magnum opus and a film regarded as even scarier than Halloween. His low-budget siege film Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) and post-apocalyptic comic book Escape From New York (1981) are all time action movie classics.

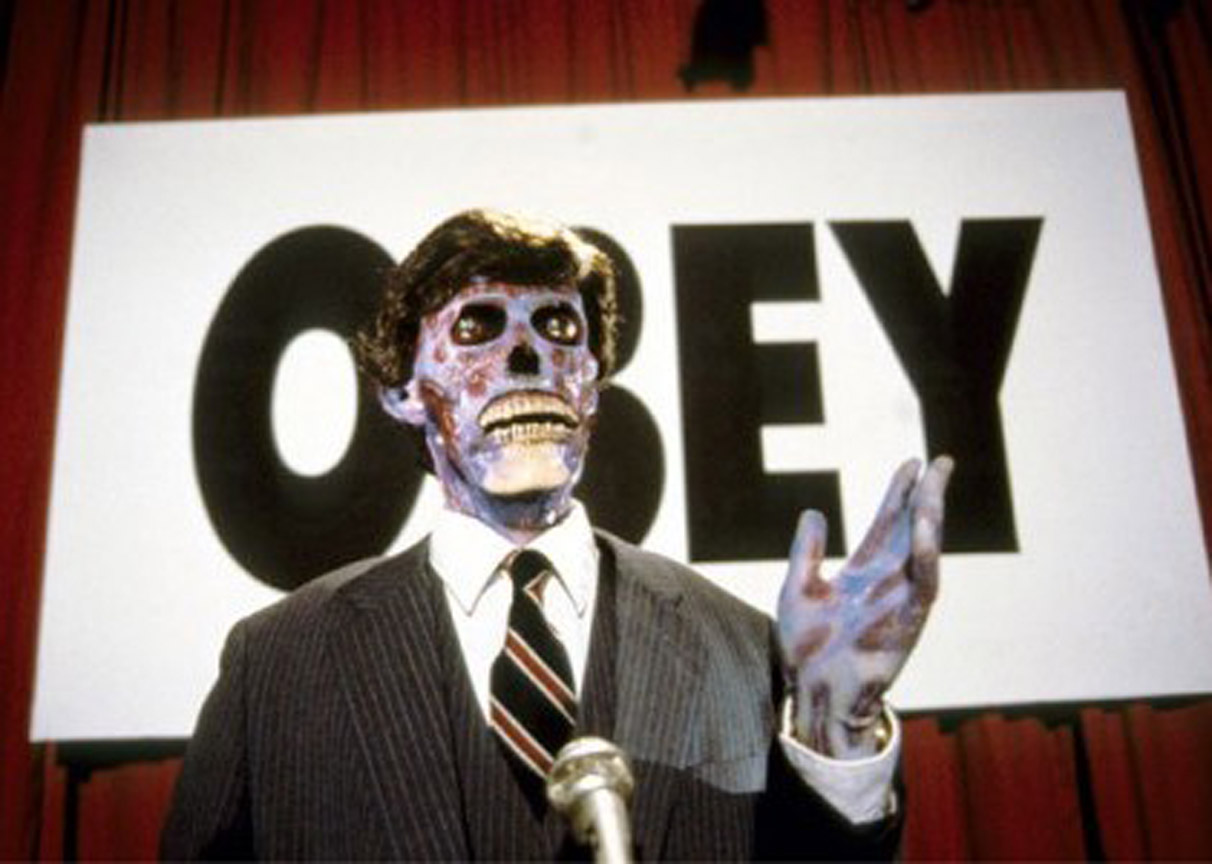

Though they lack the streamlined efficiency of Halloween thanks to diffuse casting and storytelling, The Fog (1980) and Prince of Darkness (1987), creeped us out. They Live (1988) took on the rampant consumerism of the Greed Decade in lighthearted but provocative fashion, bubblegum and kicking ass included, while his riff on Asian fantasy martial arts epics, 1986’s Big Trouble In Little China, joined that film in cult film adoration.

But once 1990 hit….that was it. Carpenter seemed to lose the magic touch that made him one of the most renowned genre luminaries of the 70s and beyond. Part of it was do to simple apathy: the blunt talking director made no secret of his increasing disinterest in movie-making, preferring to wanna spend his time playing videogames, smoking pot and watching basketball. And that disinterest shows, especially in dreary and flat films like his 1995 remake of the B-movie killler kid classic Village of the Damned.

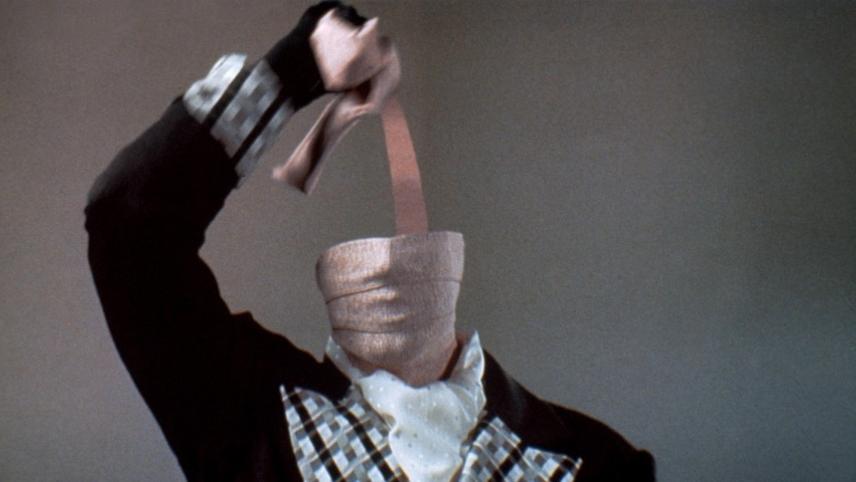

Luckily, the worst film of this downfall — and his worst in general — came first, with 1992’s miserably unfunny scifi-action comedy Memoirs of an Invisible Man, starring a stiff and heavily miscast Chevy Chase as a milquetoast who is accidentally injected with an invisibility serum. His first studio-backed effort since the box office failure of The Thing (his features after were studio-distributed but not financed), it is driest and most anonymous film.

While they look better in comparison to Memoirs, films like TV movie Body Bags (1993), bloodsucker western Vampires (1998) and bland ghost story The Ward (2010) — made after a decade long-absence from filmmaking — are watchably mediocre at best, while Ghosts of Mars is a terrible, self-plagiarizing mess.

There’s been one bright spot in all this, however: In The Mouth of Madness, the apocalyptic Lovecraft homage from 1995 that is his last great film. Twenty years later, it seems that Carpenter is content to noodle around in the music studio then deliver another film worthy of his lofty reputation.

Author Bio: Johnny Donaldson is a Massachusetts-based actor, producer and film critic who is probably drinking a craft beer and petting his cats when he isn’t watching movies.