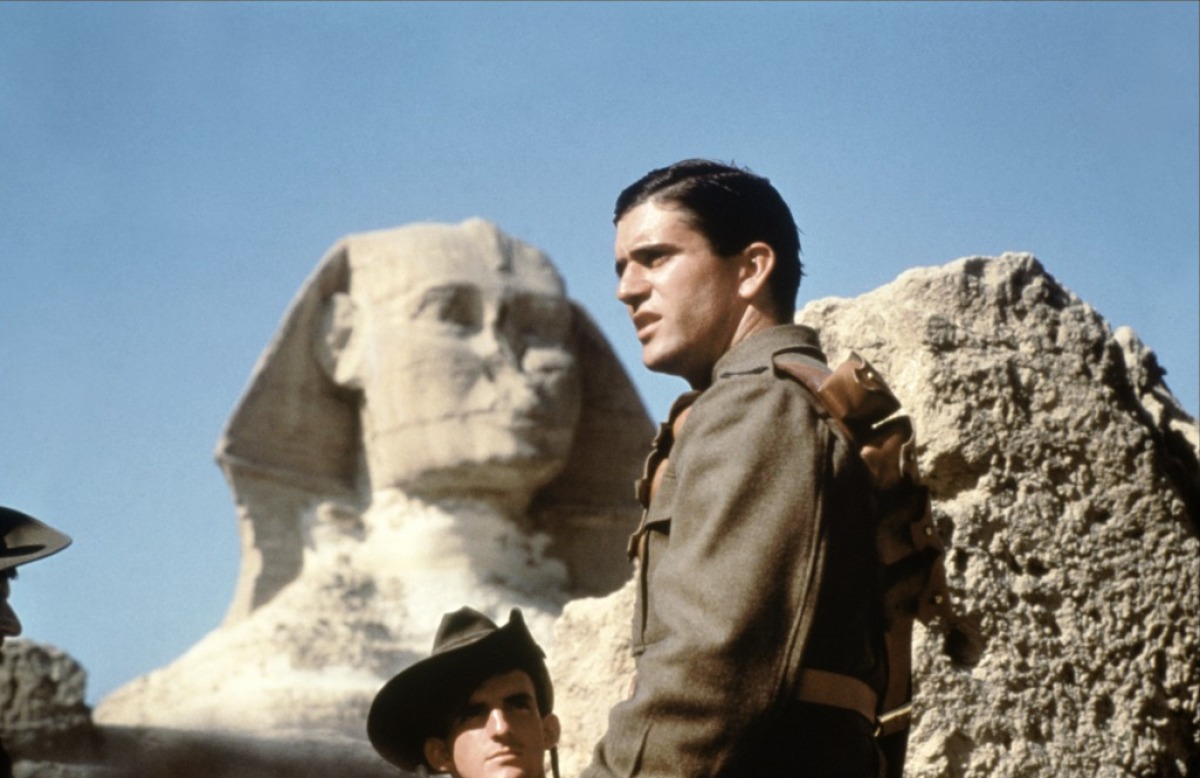

6. Gallipoli (Peter Weir, 1981)

Peter Weir is a pioneer of Australian film and arguably, alongside the visionary George Miller, the most influential and important director in the history of Australian cinema. Following the success of films like The Cars Ate Paris, Picnic at Hanging Rock, The Last Wave and The Plumber, Weir had emerged as the leading director of the Australian New Wave. This enabled him budget of 2.8 million to film Gallipoli, an Australian record at the time.

The film follows two young runners from different backgrounds who decide to join the war effort, ultimately landing on the beaches of Turkey. Centering on Archie, the angelic-looking idealist, and Frank, played by Mel Gibson, a penniless labourer of Irish heritage who initially has little interest in fighting for the British Empire, Gallipoli is essentially a film about the loss of innocence.

The disaster that was the Gallipoli campaign is well known to Australians, a fact which gives the entire film this tinge of sadness, as the audience knows what fate awaits these men.

Although Gallipoli certainly plays into the packaged ‘Australianness’ that was present throughout much of the New Wave, with the constructed traits of mateship and loyalty coming off quite heavy-handed, the film is still, at its heart, the story of two young men who go to war for reasons beyond their knowledge or control. The climax remains one of the great tear-jerking moments in Australian film history.

7. Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (George Miller, 1981)

The 1981 follow-up to Mad Max is exactly what a sequel should be. The Road Warrior is more ambitious in every aspect, benefiting from a budget of 4.5 million, and looks to build upon the world created in the original.

The film opens with an explanation for the now completely desolate world: an energy crisis and resulting global war, ‘guzzolene’ is now the wasteland’s most prized commodity. Our hero, Mad Max Rockatansky, has been reduced to a scavenger, scouring the wasteland for food, water, bullets and petrol. Where the original was more of a revenge flic, The Road Warrior takes the form of the classic Western. Max only cares about himself, his ability to care for others scarred by his dark history.

Expanding on the fictional world of Miller’s original film, The Road Warrior introduces a new breed of gang, punk-inspired ‘marauders’ whose thirst for blood is only matched by their thirst for guzzolene.

While the second film of the franchise strips back on character development and storytelling, it delivers ten-fold in every other aspect. The not-too-distant future style of the original has developed into something far more otherworldly, the gangs have morphed into sadomasochistic beasts that prey on the weak, while the action-sequences deliver a significant improvement on the first film’s low-key style.

The Road Warrior finishes with a spectacular 15 minute car-chase sequence that re-enforces the film’s larger ambitions and cements it as one of the greatest action films ever made.

8. The Man from Snowy River (George T. Miller, 1982)

No, not that George Miller, but a technically ambitious film in any regard. The Man from Snowy River is based on the much loved Banjo Patterson poem of the same name, and features a heavyweight cast, mixing well-known Australian stars like Jack Thompson and Sigrid Thornton with Hollywood royalty, Kirk Douglas.

When a young rancher’s father dies, he must prove that he worthy of inheriting the family station. The only way to do this is to work for Harrison, played by Kirk Douglas, a well-known cattle-station owner in the area. After initial belittlement at the hands of the more seasoned cowboys, the young rancher is able to prove his manhood, earning the right to work the land.

A simple premise that shows clear lineage to the Hollywood Western, Miller’s movie is the seminal landscape film of the Australian New Wave. The landscape, the Snowy River country, is positioned as mythical and awesome, something that only a very special breed of human can defeat, and in doing so, prove their masculinity.

The film unapologetically presents this packed image of Australia, merging the classic Australian emblems of the bush and the Aussie battler to create a picture that would almost come across as satire if not for the presence of Kirk Douglas. The nationalistic values on show are countered by a film that is very clearly influenced by American melodrama and Western cinema, creating a juxtaposition of themes and styles that gives The Man from Snowy River a sense of uniqueness.

Where the film reaches worthy heights however, are the wonderfully orchestrated horse-chases that more than match its American Western counterparts, sequences that remain impressive to this day.

9. The Year of Living Dangerously (Peter Weir, 1982)

Peter Weir’s third film on this list and Mel Gibson’s fourth, The Year of Living Dangerously remains Weir’s final Australian film, following up this 1982 entry with the Harrison Ford-led Witness, a film that earned Weir the first of four Academy Award nominations for Best Director.

Another ambitious effort from an Australian director dealing with limited supplies, the narrative begins with a naïve journalist played by Mel Gibson who enters an Indonesia on the brink of a civil war, where he befriends photographer Billy Kwan and falls in love with the British diplomat, played by Sigourney Weaver.

Peter Weir is an atmospheric filmmaker, from The Cars that Ate Paris to Picnic at Hanging Rock to Gallipoli, he has always been able to paint vivid pictures that transfer his viewers into the worlds he is trying to create. The Year of Living Dangerously is no different, using the Philippines as a stand in for Jakarta, Weir’s film depicts a tropical world that is hot, dirty and engulfed by poverty. The tension that erupts from this picture almost feels welcome in such a world.

Weir makes sure not to take a political stance, and the film frustratingly lacks in detail on occasion, but this is overshadowed by the love affair between the two leads, a foreign romance almost gives the film a Casablanca-like tinge. In this sense the movie is certainly a melodrama, and it feels atypical in the era of Australian filmmaking, an idea cemented by the performance of Linda Hunt, playing the male dwarf photographer.

Hunt’s role as Billy Kwan is perhaps the best of the Australian New Wave. The fact that it is a woman playing a man is quickly forgotten in Hunt’s performance, in which she plays Billy with a well-hidden vulnerability, a person whose intelligence is constantly belittled because of his size, Billy counters this by cleverly manipulating everybody around him.

Where the bigger-budget Australian films of the era showcased characters with clear motives and a Manichean sense of good and evil, Hunt’s Billy is mysterious and unpredictable, a character that is misunderstood and underestimated. Watch the film if only for this performance, for which Hunt deservedly won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress.

10. The Year My Voice Broke (John Duigan, 1987)

Australian audiences eventually got tired of the ‘gum nut’ nationalism landscape film that came to represent Australian cinema in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The commercial failures of films like Burke and Wills and The Lighthorseman signalled a need for change.

This initially came through Crocodile Dundee, a self-aware comedy in which Paul Hogan’s Mick Dundee is the complete personification of an outsider’s view of the Australian bushman. The film became the successful Australian film of all time, in doing so reinforcing the notion that Australian cinema makes a concerted effort to display these stereotypical qualities of ‘Australianness’.

Following Crocodile Dundee came The Year My Voice Broke, a transitional film that saw Australian cinema move away from valorising its subjects and settings. The film opens with several stagnant shots of the pastoral setting, with distant mountains in the background creating the same sense of isolation that flowed through Sunday Too Far Away, before moving into a monologue delivered by the film’s protagonist, Danny.

Danny is smitten by his childhood sweetheart, Freya, who is in turn in love the town’s resident bad boy, Trevor, played by a young Ben Mendelsohn. While the teenage love triangle premise is certainly typical, the resulting product is anything but. The isolated township is depicted as hateful, oppressive and hypocritical, and Duigan’s subversion of the usually celebrated traits of masculinity and mateship bring back memories of Wake in Freight, such is the negativity that surrounds each ocker-type character wearing the iconic Akubra hat.

While many of the themes that run through The Year My Voice Broke are common in the teenage genre, such as sexual awakening and isolation, Duigan gives an alternative look at them here.

The seminal awkward teenager, an archetype of teenage film, is presented here in a much more naturalistic sense, as the characters and actors in The Year My Voice Broke actually feel like awkward teenagers. Their pimpled faces and somewhat novice performances make for a much more personable film, and one that can’t be missed in detailing the history of Australian cinema.

Author Bio: Ned is a recent graduate of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. He completed his thesis in his final year of study, in which he focused on realism in Australian cinema, but he is also a massive horror buff and lover of independent cinema. Ned plans on undertaking a PhD in 2017.