5. The Seventh Seal (1957)

Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) is a knight returning to Sweden from the Crusades. He is disillusioned with his faith and, after saying silent prayers on a beach, is greeted by Death in the form of a man (Bengt Ekerot) in a black cloak. After it is revealed that Death has come for Block, he challenges Death to a chess match hoping to delay his passing.

After witnessing the plague in Sweden and participating in the crusades, Block is familiar with death, but has undoubtedly categorized it as an event that happens to others, as Heidegger says inauthentic mankind inevitably does. Death’s personified arrival removes this possibility, freeing Block from his normal chivalric knightly duties and forcing him into the most significant chess match of all time.

Block is weak. He finds authentic life to be too much of a burden and, unable to wrestle with the Heideggerian beast of Being-toward-death, he remarks that “no one can live in the face of death, knowing that all is nothing.” Bergman is thus rejecting Heidegger’s existentialism, calling it meaningless nihilism and saying that its abyss is too difficult to bear.

As in all Bergman films, there is tension between faith and agnosticism. Block never truly resolves this tension, and seeks throughout to avoid having to rely on faith alone. Just before the end, he prays to God, asking for mercy, as he is “small and frightened and ignorant [in the face of death].”

4. Synecdoche, New York (2008)

Caden Cotard (Phillip Seymour Hoffman), a theater director in Schenectady, is in an existential struggle. His wife and daughter leave him, he has awful flings with coworkers and employees (including a lady from the box office named Hazel (Samantha Morton)), and his health continually deteriorates such that viewers expect him to die at any moment (from the very beginning of the film, no less).

He knows the end is near, and that he is a Being-towards-death. He even says “we are all hurtling towards death, yet here we are for the moment, alive.” Yet, despite this direct Heidegger reference and in spite of his self-awareness, he is intent on finishing his magnum opus, a play. With the help of a MacArthur fellowship, he dedicates his entire life to writing a play about just that, his entire life.

Throughout the film, Caden is stalked by an older man, Sammy (Tom Noonan). He casts Sammy as himself and allows Sammy to recreate all of his past failures and to, in a sense, live out his life for him, even to pursue what was perhaps Caden’s truest love, Hazel.

What is promising about Sammy and his portrayal of Caden is that he is able to do that which Caden is not: to live authentically and acknowledge and embrace death. In fact, Sammy is not only able to right some of Caden’s wrongs, but he is even able to bring about his own inexistence, in true artistry, and to thereby awaken Caden from his melodramatic inauthenticity. The entirety of the film is a blurring of fact and fiction, as theater becomes Caden’s reality.

There is only one way to unblur it. Hazel decides that she loves Caden and must break off relations with Sammy (a choice to move from fiction to reality), prompting Sammy’s suicide. It is this suicide, and a cue from the stand-in director Millicent Weems (Dianne West), that allow Caden to do what was inevitable from the beginning of the film: to die.

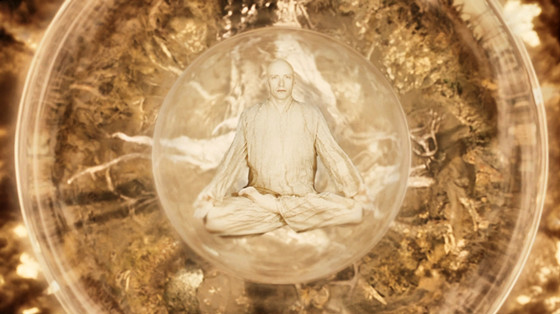

3. The Fountain (2006)

The Fountain is simultaneously Aronofsky’s deepest and least-appreciated film, perhaps because it takes place simultaneously in three plots each separated by 500 years or more. The core and perhaps most “real” plot is that of Tom Creo (Hugh Jackman), a 21st century doctor who is losing his wife (Rachel Weisz) to cancer.

As she suffers and he searches for a cure, she writes a novel about 16th century struggles with the Inquisition, the second plot, in which she plays Queen Isabella and sends her betrothed Tomás Verde on a search for the Tree of Life. Her novel features the Mayan star Xibalba which, in the third and futuristic timeline, Tommy departs for in hopes of reversing the past and undoing her death.

The Fountain is, in short, a struggle to find permanence and to overcome Being-towards-Death. Yet, the twist is that in all three timelines, Jackman’s character is not dealing with his mortality, but with Weisz’s, who is either hurdling towards death or has already crossed its curtain.

Jackman’s characters are each convinced that death can be avoided. As Tom Creo says, “death is a disease, like any other, and there’s a cure.”

Jackman obsesses, caught in the strictures of the day, obviously aware of death and inexistence, but convinced that an authentic approach to Being-towards-Death combined with faith, science, or interstellar powers can change the very meaning of existence. Yet, despite this attitude and Jackman’s triple reincarnation, Aronofsky’s answer is firm: man cannot overcome.

We are hurtling towards inexistence, and any resistance is a waste of time (and your life). Tomás Verde dies after drinking sap from the Tree of Life and thus fails to bring back any for Queen Isabella, Tom Creo fails to save his wife Izzy and loses all of his friends along the way, and Tommy reaches Xibalba only to watch the Tree of Life he is transporting die moments beforehand as his dreams of resurrection slip away.

If there is to be anything after our deaths, we must accept it entirely on faith, as this “Thomas” does, for it is not something Aronofsky allows his viewers to see.

2. The Thin Red Line (1998)

The Thin Red Line was Terrence Malick’s great return to film after 20 years of silence. His last films, Days of Heaven and Badlands, made him legendary, allowing him to have such a star-studded cast for his return that expectations were high.

The Thin Red Line didn’t meet these high expectations from the general public, because it was not an action-packed war movie like Saving Private Ryan, but was instead a meandering muse on Heidegger, evil, and other serious issues that only a personal student of Martin Heidegger could create. That’s right, Malick studied Heidegger at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar and actually met the legendary philosopher in his cabin in the Black Forest of Germany.

Army Private Witt (Jim Caviezel) is a man lost in the Melanesian sea and the sea of soldiers fighting in the pacific in WWII. Loyal to C Company, he is in and out of the fight at Guadalcanal as troops serving under Lieutenant Colonel Tall (Nick Nolte) try to claim hill 210. The fight is intense, and many young soldiers are shot down and die horrible deaths.

The film begins with Private Witt recalling his mother’s death: how she met it with peace and wasn’t afraid to die. He had been afraid of “the death [he had] seen in her”, but wanted to meet death with the same calm. As he says, “that’s where it’s hidden—the immortality [he] hadn’t seen.” Need I say more?

Malick repurposes war as a medium to present questions of mankind: what is our relationship to nature? to each other? to ourselves? These questions are asked in voiceovers by Private Train (John Dee Smith), who longs for his soul to “be in [God’s] now”.

The muses of the voiceovers are not mere pantheistic dreams, but force viewers to be self-reflexive and consider their very Being and the possibility of their inexistence. Note also that Malick operates primarily via voiceovers, which themselves question existence, because they are produced without a physical representation.

Malick, in his very project, is doing exactly what Heidegger asks: he uses film to invent a new language, one capable of communicating questions of Being separate from connotations and strictures of modern society. In other words, his project uses film as the language with which to authentically question Being and existence. It is Heideggerian cinema, and cinematic poetry.

1. The Sacrifice (1986)

Another influence on Malick is the great Andrei Tarkovsky, poet, filmmaker, and friend of Ingmar Bergman. His project was similar to Malick’s: to create a cinematic poetry that could express questions inexpressible in normal language. His films feature Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Hemmingway, and, yes, Heidegger.

In The Sacrifice, Alexander (Erland Josephson) is a retired actor working in the field of aesthetics, living with his wife and son “Little Man”, currently mute due to throat surgery. After some direct-from-Nietzsche dialog, it is revealed that Alexander has no faith and is wearied by the world, and so he has moved to the seaside and harangues well-wishers with rants against modernity and, you guessed it, modern man.

Shortly thereafter, catastrophe strikes, as nuclear holocaust begins. Despite his faithlessness, Alexander begins to plea with God, vowing to sacrifice all that he has to undo this devastation. The rest of the film takes place in multiple realities and on multiple timelines, as the Being-toward-Death state begins to takeover and haunt Alexander’s numbered remaining hours. He must choose between faith and science.

Should he sacrifice all that he has? Can the technology that has wrought such devastation redeem mankind in some way? Depending on your reading of Heidegger, both faith and reason can obscure man’s Being, or perhaps one can help him come to terms with it. Alexander’s dilemma ends not with Heidegger, but with Kierkegaard and a dialectic between faith and insanity.

The film ends with what is perhaps the most existential line possible, not going back to the pre-Socratics as Heidegger would have liked, but conceivably returning further to the origins of time, according to the Gospel of John. Finally Little Man utters his first and only line: “In the beginning was the Word. Why is that, Papa?”