6. Babbette’s Feast (1987)

Gabriel Axel’s Babette’s Feast is a film about love, charity, faith, and renewal. As if that didn’t sound Kierkegaardian enough to put it onto this list, it takes place in Kierkegaard’s Jutland and one of its main characters, General Lorens Lowenheilm (Jarl Kulle), is basically a stand-in for Kierkegaard. Like Kierkegaard, he travels to the Jutland to stay with his aunt, is engaged and decides to break off his engagement, and ultimately reclaims his faith after a wayward childhood. But, enough of these surface similarities.

Babette’s Feast warrants a watch because of its pious charm. Babette (Stephane Audran), a “lowly servant”, has decided to prepare a feast for two Danish sisters and their church friends after winning the lottery. Despite the seeming religious fervor of the people of the church, they are a divided and quarrelsome bunch.

Can Babette’s artistry, love, and charity repay the sisters for all they have done and, more importantly, can she remind everyone of the love of God and the reason for their faith? Drawing on Kierkegaard’s teachings in Fear and Trembling, Axel gives us the answer.

7. Noah (2014)

Aronofsky’s Noah was praised and criticized so much so that it made almost 50 million dollars for its US release during opening weekend alone. Why did it receive so much notoriety?

Like Kierkegaard, Aronofsky chose to interpret a passage of scripture in an unorthodox way and, like Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, Aronofsky’s goal was a bit bigger than just some ordinary recreation of a biblical text. With Russell Crowe, Anthony Hopkins, and Emma Watson, the film was sure to be a blockbuster, but I think it was one of the few that is built upon an unappreciated philosophical depth worth serious analysis.

At its core, Noah is about the silence of God, the problem of good and evil, and dialectical nature of faith. Everything that Noah does is based on an unwavering faith in God, from building the ark to raising his children according to God’s commands. Yet, one of the most trying tests of faith he faces (and an Aronofsky addition, no less) is when he is tasked with sacrificing his grandchildren so that he can put an end to the human race. Sound a bit like a Kierkegaardian setup of the Abraham and Isaac tale?

8. Mr. Nobody (2009)

Jaco van Dormael’s Mr. Nobody is a powerful film about choice, the problem of evil and God’s existence, marriage and family, and determinism. In it we see Nemo Nobody (Jared Leto), who is faced with an impossible task of choosing between his soon-to-be separated parents.

Most of the film takes place in separate imaginary timelines which, to some extent, play out the consequences of choosing his father over his mother and vice-versa. What a hard thing to ask of a young child (and what a shame it is that society allows this question to be asked over and over and over again).

For Kierkegaard, existence is tied to choice. Man’s essence is a result of his free will and the consequences of his choices. In Mr. Nobody, we see just this, as Nemo’s decision affects who he is and all of those around him. Thus, choice creates a dialectical essence for man, where his singular choices are contrasted to the universal.

Man’s choices may be what makes him man, but they also create an inexorably crushing burden of despair, which Normael shows us in Nemo’s last days. At what point in life should one have to make such momentous decisions? Is it really fair for us to put such a burden on young children?

9. The Dark Knight (2008)

Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy and The Dark Knight in particular were wildly popular superhero films that had a depth all other superhero films lacked. The Dark Knight speaks to terrorism and fear generally, as Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) faces off against Kierkegaardian dread, loss, and isolation. Bruce is a stand-in for Job in many ways, as a wealthy man that is forced to watch all he knows and loves to crumble around him.

Ultimately, both Bruce and Job receive everything they had back two-fold, both materially and spiritually, although I’m going to guess that Job’s tormentors were a bit more frightening and serious than Bane and the Joker.

Not only is Batman a stand-in for Job and a Kierkegaardian Knight of Faith (his faith is in the good will of the people of Gotham City), but the film also features a Kierkegaardian repetition. When Two-Face forces Commissioner Gordon to reassure his child, Batman witnesses a repetition from his father’s death. This time, he is able to step in and save Gordon’s son, the sort of act that Kierkegaard believes brings hope to the world of restoration.

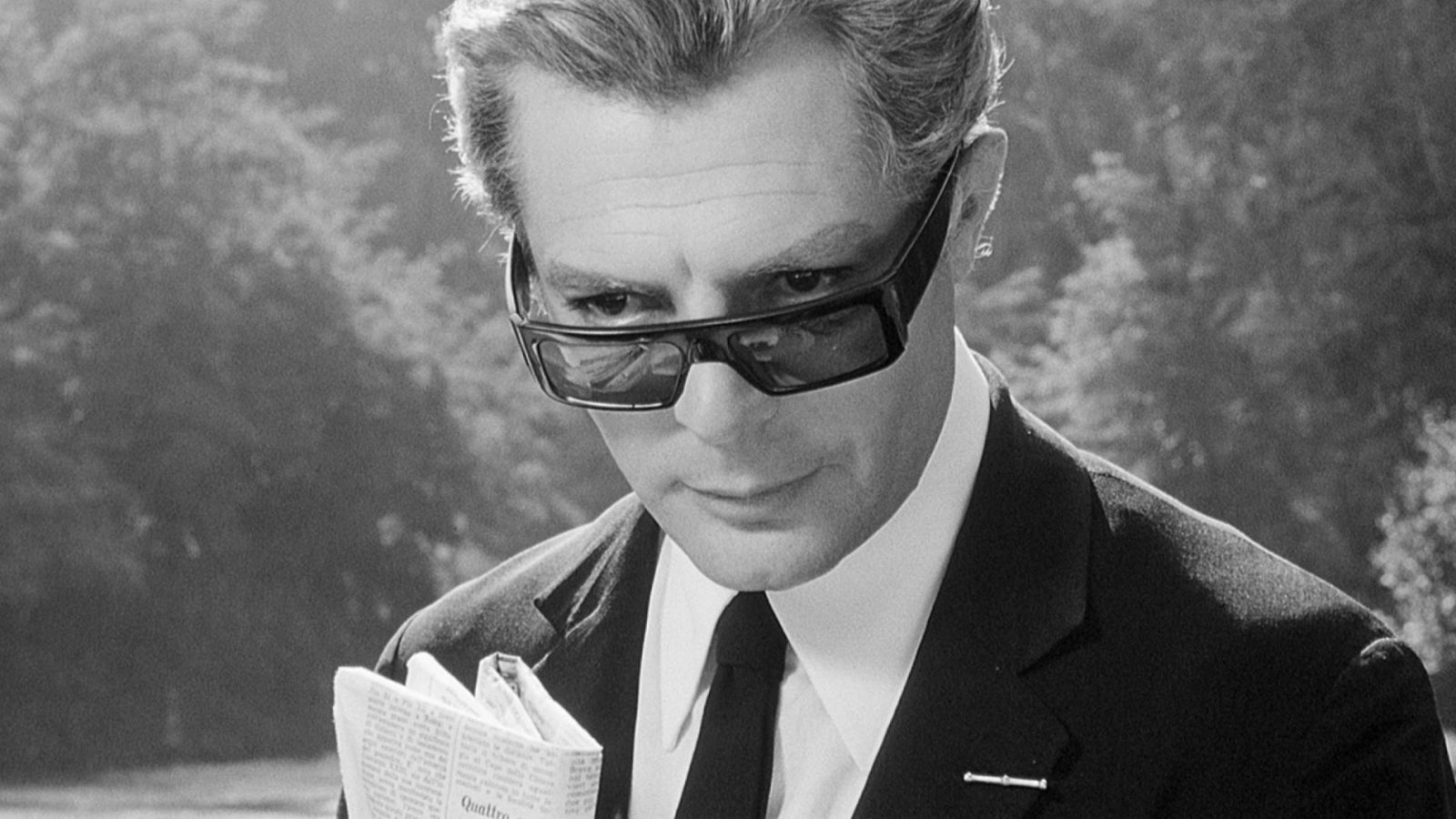

10. 8 ½ (1963)

Frederico Fellini’s 8 ½ is about Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni), an Italian filmmaker who is working on his upcoming movie. The problem is, Guido can’t find any inspiration, and people will not leave him alone. His mistress, wife, producer, and friends keep harassing him, and the pressure keeps mounting, thanks to his past successes, for him to produce one last masterpiece. In response, he leaves, sojourning in the realm of fantasies, memories, and dreams.

What exactly is 8 ½ all about? Aside from being autobiographical, Fellini is trying to portray humanity and its quest to find meaning in life. Everyone in the film seems to think Guido has found life’s meaning and is struggling to put it into film. Fellini is actually saying something rather different: faced with the despair and dread of life (a Kierkegaardian notion), art and everything else not only becomes meaningless, but it also becomes inauthentic and impossible. What can Guido do to get out of this situation?

Author Bio: Ben Wilson is a recent graduate of Yale College, where he studied Philosophy and Political Science. A film buff and addict, he views film as the proper medium for philosophy in the 21st century.