5. Melancholia

Melancholia is probably the cleanest and most accessible of the von Trier films. It follows Justine (Kirsten Dunst) through two of the biggest three events of her life: her wedding and her death. Of course, it does so in a grotesque, vulgar, and nihilistic way as any von Trier film does, but Melancholia has a depth to it that leaves viewers shaken to their core. It’s hard to find someone who doesn’t feel strongly one way or another about the film.

Why is that? Because of the film’s portrayal of death hurtling towards everyone in such a visibly powerful way. Most of the characters are unable to elevate their despair under such great pressure, but Justine is unusually gifted because she is able to accept and even come to peace with her inexistence. It only takes a spell of melancholic depression to get her there.

4. The Fountain

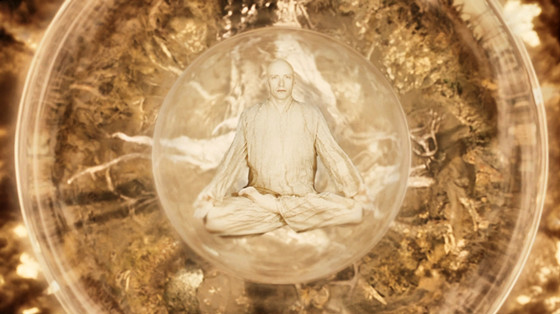

One of my personal favorites, The Fountain follows 2 characters over 3 separate timelines. Tom Creo (Hugh Jackman) is on the verge of losing his wife Izzi (Rachel Weisz) to cancer, while Tomas Creo the conquistador is searching for the fountain of youth for Queen Isabella in foreign Latin America, all while Tommy Creo is attempting to bring the tree of life to Xibalba, the Mayan star. The realness of each of these plots is irrelevant, but the emphasis of “creo” and the looming death are what matter.

The Fountain is about death: its finality, irrevocable nature and what that means for the human race. Nothing Jackman is able to do in any plot can overcome death, despite his unwavering faith in each effort. It seems his faith is misguided, whereas Weisz’s death is certain. She does a much better job of accepting this fact than Jackman, unfortunately.

3. No Country for Old Men

Perhaps the best Coen Brothers film, though to be sure a strong case must be made for O Brother Where Art Thou or Barton Fink, No Country for Old Men features a gripping plot and compelling acting.

Anton (Javier Bardem) is a killer sent from hell, wreaking havoc across a wide barren landscape in search of a lost payment for a massive shipment of cocaine. Meanwhile, the sheriff (Tommy Lee Jones) witnessing these atrocities is searching for something for some way to make sense of everything. What do I mean by that?

Well, to be sure, the sheriff is looking for the clues to track down Anton and end his mad killing spree, but he’s really looking for something deeper. In the spirit of Cormac McCarthy, whose book spurred this film, the sheriff is looking for a way to go back to a time where things fit coherently into a philosophy and worldview.

The entropy of the modern world is too much for any old man like him, and there’s no way to restore order when nothing is holy (and surely nothing is holy for Anton). Relativism is the sheriff’s great foe, but it’s hard to reject it completely in his time.

2. Synecdoche, New York

A Kaufman masterpiece filled with phenomenal acting by the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Synechdoche, New York is not just a film in which its characters search for meaning when faced with their deaths.

Rather, Synechdoche, New York is a film searching for its own meaning as it refuses to die. Sure, it is a long film, but the meta level at which its Heideggerian dialectics operate, the film, which stands for Caden Cotard’s (Hoffman’s) play, and Caden refuse to die or even acknowledge that things could come to an end.

A brief synopsis: Caden Cotard, a playwright and director, has made it big, or at least big enough so that he has unlimited funding for his next unwritten play. That play, like his life, is troubled from its inception, but Caden has a way of prolonging both (and a couple of romances along the way, too).

His wife leaves him and takes his daughter, he is continually diagnosed with horrific diseases, and his play suffers several serious setbacks. And yet, Caden is only able to surrender to death after he receives a stage direction telling him “die”.

1. The Tree of Life

While not my personal favorite, The Tree of Life is probably the deepest and best made film of the 21st century. Award winning director Terrence Malick’s crowning achievement, it features stellar performances by Jessica Chastain and Brad Pitt.

A Heideggerian poesis of film, it is built around a passage in the book of Job in which God says to Job something to the effect of “who do you think that you are?” A response to the untimely death of his brother, the film is about Malick’s childhood and, more importantly, how his family dealt with that loss.

It’s hard to offer words that can emulate the beauty and depth of the film (which may be why Malick often uses so few, both on and off the screen), and it will take several viewings to truly understand the film and catch most of the symbols Malick uses (windows, water, trees, stairs, etc.), but it is well worth the time.

Many are quick to criticize Malick for his lack of plot, but The Tree of Life features plenty of plot for the careful observer (in fact, all the plot since the dawn of time, in a sense), which was more than enough to win it that ever-rare palm d’or.

Author Bio: Ben Wilson is a recent graduate of Yale College, where he studied Philosophy and Political Science. A film buff and addict, he views film as the proper medium for philosophy in the 21st century.