5. Platoon (Oliver Stone, 1986)

Platoon is a feverish Vietnam film, made with a sense of grace and poetry by writer/director Stone, with Richardson doing some of the grittiest work of his career in this Oscar-winning classic.

Because the story was informed by Stone’s real-life war experiences, the film has always carried an impressive sense of honesty and realism, and when combined with some of the more surreal aspects to the film, Richardson was able to create the perfect visual balance of stark violence and introspective beauty, while never turning the camera away from a potential atrocity or moment of severe, gory consequence.

The nighttime action sequences are positively haunting, with the camera capturing the explosive action with a tremendous sense of fury and discipline, while all of the actors were given plenty of room to create sympathetic characters who would all get their chance to shine in front of Richardson’s camera. Platoon has long been considered one of the defining war films of all time, and it’s easy to see why.

4. The Doors (Oliver Stone, 1991)

Music. Poetry. Sex. Life. Death. LSD. Reefer. Whiskey. Fame. Rock ‘n Roll. I’m not sure if there’s ever been a filmmaker and subject matter more aligned than Stone and The Doors, and in this film, Richardson went wild with the concert footage (still the best ever shot for a feature), resulting in one of the greatest non-documentary concert film/band biopics ever made.

The filmmaking aesthetic on display in The Doors literally stretches the bounds of what you might expect from the material, with Richardson providing the film with a dreamy, stony camera style that seems to float and glide from one interlude to the next. There’s some bravura stedicam work on display in this film, not just in the utterly bonkers concert moments, but in the quieter moments between the band members; it’s actually possible that more than 50% of this film was shot with a stedicam, which is crazy to ponder.

The idea that Val Kilmer wasn’t shown any Academy love for his soul-baring work in this film is disheartening, as Richardson’s camera caught every single moment from this magical performance; it was more or less a case of possession rather than simple acting. And while the self-conscious sense of style was certainly upped to a high degree in this film, it’s the clarity and dramatic pull of the images that keeps everything grounded even when the narrative goes off into surreal directions or tangents (that sequence in the desert!)

Stone and Richardson’s filmmaking was unapologetically aggressive and volatile – you get a contact high while watching this movie. For some it’ll be too much. For others, it’ll be that magic combination of filmmaker, cinematographer, and subject matter where it all adds up to something positively electric.

Richardson’s work on The Doors was boozy, smoky, and downright hallucinatory, with the swervy cinematography and the dynamic editing patterns coalescing to create a trip-like tableaux of a man who believed in a “prolonged derangement of the senses.” It’s absolutely insane to think that Stone and Richardson had both JFK and The Doors in cinemas in the same year; I guess they felt that sleep wasn’t essential.

The outdoor concert sequence with Kilmer running around in the middle of all the spectators is outrageous in attempt and flawless in execution, with Richardson and Stone literally losing their cinematic minds all over the place. This is spectacular stuff from top to bottom, and a reminder of those fearless days from Stone and Richardson where the possibilities seemed endless.

3. Casino (Martin Scorsese, 1995)

Casino is an utterly engrossing saga of Las Vegas sin and sleaze from the very first masterful frame all the way until the last. Some have called it Goodfellas Gone West, and that’s not far off, but stylistically, the two films are very different, while of course sharing some similar traits. Richardson was in full-on flamboyant mode here, with massive crane shots, huge camera-arm movements, with as dynamic of a sense of how to shoot in widescreen that can possibly be referenced.

The film is truly epic in both visual scope and narrative structure, with one element complimenting the other, as Scorsese ladled on the blood, profanity, and gangster tropes that everyone would expect from the master of this particular milieu. There’s a journalistic sweep that encompasses much of Casino, with Richardson’s always-searching camera gliding over the action, covering the various back-room deals and violent confrontations with extreme style.

Scorsese was obsessive in the details both large and small during Casino, which allowed Richardson the chance to gaze his camera upon the glitz and glamour that Las Vegas exudes. There’s an obscene amount of three to five minute long stedicam shots in this film, which gives off an observational quality from moment to moment. It’s sort of ridiculous to be honest. Richardson lit Sharon Stone like a goddess in this film, always showing off her eclectic wardrobe and sexy make-up to maximum effect.

Everyone in the cast was just perfect, with Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci doing their best “one-two” with each other, while Richardson and Scorsese caught all of the sly moments from these two actors that helps make this film what it is – a study of excess and greed and power.

There’s a level of verisimilitude that Richardson and his crew brought to this film, from the practical locations to the fully decked out sets to all of the character actors and “faces around the tables” that totally make this movie what it is – a perfect distillation of a bygone era.

There’s also a freewheeling sense of visual flamboyance (this is Vegas after all!) that Casino possesses, which separates it from other genre entries, and it felt like the next logical step for Scorsese in terms of his fascination with this subject matter.

2. JFK (Oliver Stone, 1991)

No other film walks, talks, and looks like Stone’s JFK, and a large reason for that is the hot, overhead-light intensity of Richardson’s smoky and shadowy widescreen cinematography.

The dense narrative covers the various conspiracies concerning the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and through Richardson’s studied and smart use of framing and film speed (slow-motion is used in this film to maximum effect), this three-plus-hour film hurtles by at an alarming speed (the fleet editing is also part of it), with Richardson’s masterful images creating a time capsule of an America bruised and hurting from societal unrest and uncertainty.

New Orleans, of course, has a very distinct atmosphere, and since much of the film is set there, Richardson was afforded the opportunity to shoot in some very unique locations, while still getting the expected mileage out of the visual chances that Washington DC provides. There’s a classicism to Richardson’s images in this film, which is one of the reasons it likely resonated with Oscar voters, as this was the first time that this legendary cameraman would receive the top prize from the Academy.

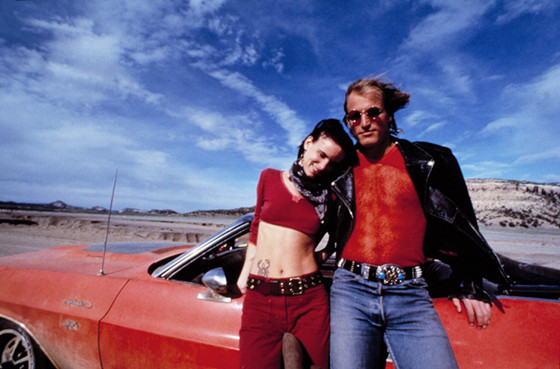

1. Natural Born Killers (Oliver Stone, 1994)

Richardson’s best work also happens to be one of cinema’s boldest films of all-time, Oliver Stone’s fever-dream media satire masterpiece Natural Born Killers.

It was here that a totally unhinged Stone cut loose every which way, allowing Richardson to experiment with multiple film-stocks, various lenses and filters, and differing processing techniques in an effort to create a kaleidoscopic effect of people, places, and things, all blurred together with a seething narrative rage and a sense of full-on intensity that extended into every incendiary image that Richardson crafted.

The violent and sexy and insane story of serial killers turned tabloid darlings Mickey and Mallory Knox, Natural Born Killers is the very definition of In Your Face Filmmaking, with Richardson’s hyped-up camerawork blasting the viewers senses; this is one of the most visceral movies ever conceived, and because of how trippy some of the images become, the viewer can easily get lost in the sea of ever-expanding visual information that Stone and Richardson wished to convey to the viewer.

The standout bits are too many to list, but some of the film’s most striking passages (inside of the Native American’s hut with the shifting background and hallucinogenic twist; the beat-down at the pharmacy; the prison riot) make you feel like an outlaw while watching, as Richardson’s unrelenting technique consumes the frame, with results that are nothing short of brilliant and transcendent.

Natural Born Killers is an astonishing piece of filmmaking, and it clearly represents the apex of Stone’s breakneck style, which had been pioneered by Richardson over the previous 10+ years of collaborations, and then further explored through two more cinematic efforts before their breakup. It’s a shame that these two extremely gifted artists haven’t reunited for one more swan song.

Other notable credits amongst many: Hugo (won the Oscar), Bringing Out the Dead, Eight Men Out, City of Hope, Django Unchained, The Horse Whisperer, and The Good Shepherd.

Author Bio: After spending close to a decade working in Hollywood for the likes of Jerry Bruckheimer, Tony and Ridley Scott, and Gary Ross, Nick Clement has taken his passion for film and transitioned into a blogger and amateur reviewer. Some of his favorite filmmakers include Michael Mann, Martin Scorsese, Tony Scott, Steven Soderbergh, Werner Herzog, Terrence Malick, and Billy Wilder, while favorite films include The Tree of Life, Goodfellas, Heat, Back to the Future, Fitzcarraldo, Schizopolis, The Counselor, and Enter the Void. His latest venture, Podcasting Them Softly, finds him tackling new ground as an entertainment guru, with a focus on filmmaker interviews and written analysis.