6. Fail Safe (Sidney Lumet, 1964)

Despite of the fame and recognition of Sidney Lumet, Fail Safe is still an obscure gem from the 60s. Released the same year as Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, it suffered from similarities and comparisons between the two, touching upon the same issues but with a later release than Kubrick’s film. Although not as funny as Peter Sellers’ performance, Henry Fonda and Walter Matthau make everything tense and terrible in some truly underestimated performances.

In a routine military training exercise, a plane blocks and receives an order to bomb Moscow. The incident is unclear, with the audience not knowing if the blame was on a person or a machine, but the danger of the situation is on the table. The US government then has to attack their own planes as the only way to avoid nuclear war, but it is useless.

The phone conversation between the American president (Henry Fonda) and the Soviet Union may be one of the most exciting scenes of any 60s thriller. With an excessive amount of close-ups and a free-spirited montage, most of the film’s pressure comes from formal decisions. The film avoids the mushroom cloud or any explicit vision of the nuclear aftermath; instead the horror is shown in some simple yet powerful editing techniques.

The lives of millions and the imminent disaster is discussed and decided upon by people in a room. You can calculate an atomic bomb dropping as a statistical number. The magnificent end of the film leaves this idea very clear, and again, the ones who have to suffer are not fully aware of what can happen.

5. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964)

Probably the most famous film on the list, Dr. Strangelove features a very different take on the standard Cold War film. In the same year and with a very similar plot, Kubrick demanded Lumet’s company for producing Fail Safe, thinking that the release of the film would affect the success of Dr. Strangelove. In the end, Kubrick won and could release his film before Lumet, gaining a big success, but directly impacting Fail Safe in the box office.

Dr. Strangelove also has a plot where the United States government accidentally sends a bomb to the Soviet Union, and they then try to stop it inside the war rooms. The biggest difference this film and the plot of Fail Safe is that instead of being a mechanical problem, it is intentionally made by a crazy and paranoid general. But even if the two films have the same plot, Fail Safe and Dr. Strangelove are very different and unique.

The tension and close-ups of Fail Safe are not present in Kubrick’s view, where we have Peter Sellers playing three different roles, and where the absurd of the situation is more explicit. There is no character in Dr. Strangelove that doesn’t act in an exaggerated or stupid manner.

This special approach is what made Kubrick’s film an instant classic. The humor was the perfect strategy to put things on the table and to appreciate the absurdity in everything. Even if the studio imposed the idea of Sellers playing three characters, at the end it’s a great decision, delivering three very different characters that fill every scene with energy.

Most of the darts in the film are thrown against the concept of mutual assured destruction, which dictates in any nuclear bombing, both attacker and defender will be destroyed. It sounds absurd by itself, but it was the official policy in both parts in the Cold War.

The film points every argument of it and mocks them with a crazy Dr. Strangelove (Peter Sellers) guiding the actions of the American army. It is no coincidence that Strangelove was a former Nazi doctor, the biggest enemies of United States in World War II. It’s no longer necessary to show how comedies can talk about serious issues, as it is now accepted, and Kubrick understood this very early in one of his classics.

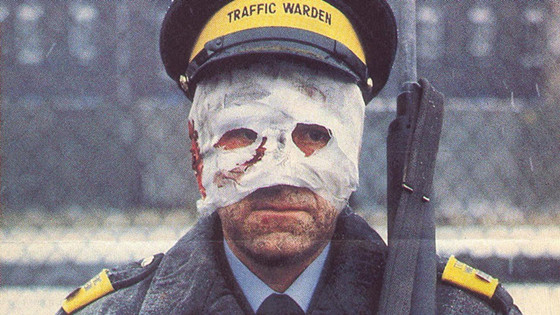

4. Threads (Mick Jackson, 1984)

In the last several years, Threads had been slowly resurrected as one of the most shocking and terrifying films of the 80s. Presented in a “mockumentary” style, it follows different families in the city of Sheffield, England. At first we have insight to personal and familiar issues, but in the midst of a pre-nuclear background. The tensions between United States and Soviet Union over Iran and Afghanistan start to escalate, making nuclear war imminent.

The film doesn’t focus on political details, and in the moments before the bombings, it instead gives a completely detailed description of the aftermath. We see the same families struggling against the different consequences of the bomb. In the 80s, scientists started to make descriptions and theories about nuclear winter.

The film was the first fictional depiction of this phenomenon. The theory dictates that the climatic effect of a potential nuclear war would make a prolonged winter in some cities. This idea had been proven to be true, and it can have an even bigger effect than the one that was described in the 80s. This film shows how everybody has to struggle to survive in the middle of this eternal winter, with one of the most graphic scenes ever shot.

It’s interesting to point out that the only two British films on this list have a similar approach and style: to imagine and make real all the fears of the civilian population, and making explicit depictions onscreen. Taking in consideration the Japanese roots of Jimmy Murakami, Mick Jackson is the only director from this list to come from a country without a direct implication in the nuclear bombings.

The British take shows a very interesting approach. These two films are like a response from the propaganda we can see in The Atomic Café: two products of absolute fear.

3. Barefoot Gen (Mori Masaki, 1983)

It’s not very easy to find information about Mori Masaki. His first works are difficult to find, and the only film he made after Barefoot Gen runs the same luck. However, the author of the work that the film is based on has its place in manga history, and knowing his life is important to understand the motive behind Barefoot Gen.

Keiji Nakazawa was born in Hiroshima and was in one of the most damaged parts of the city when the bombing occurred. Losing most of his family, Nakazawa moved to Tokyo with his mother to start a new life. Barefoot Gen works as his autobiography, and with that kind of life we can understand why Barefoot Gen hits so close to the bone. The most famous scene of the film is easily one of the bleakest moments in the history of animated film.

Similar to the effect of the next movie in the list, the first moment the bomb touches the ground everything is covered by a white light. In Barefoot Gen, the light goes over everyone and a slow zoom puts us in front of the faces and the burning flesh. Every living body turns into a skeleton after being touched by this light. It was the only feature that went to history for Masaki, but is a timeless animated feature.

2. Black Rain (Shohei Imamura, 1989)

One of the common considerations around Elem Klimov’s masterpiece Come and See is that instead of being a war film, it is pure horror, up there with the classics from the genre. This consideration (done also on this website) could be shared completely with Imamura’s Black Rain. Following a family that survived the Hiroshima bombing, the film shows how the aftermath never stops following and torturing the survivors.

Fourteen years after the bomb, the Shizuma family lives quietly in a country house. Suddenly, the diseases and consequences of radiation start to appear in every member of the family. Even as survivors, the bomb (referred by the characters as “thunder”) and its consequences never stop following them, like a permanent disease.

In the collaborative film Lumière and Company, in the Japanese segment made by Yoshishige Yoshida, we see the director telling to the audience his intention of filming the moment of the bomb, but how the results are impossible, because as soon as you place the camera you are dead. Even if Yoshishige’s argument is more metaphorical, it is true that there had been very few attempts to recreate that moment on film.

In the introduction of Black Rain, we found the bleakest live-action example. The lighting of the bomb turns the first scenes of the film into an authentic nightmare. As we follow the Shizuma family to the factory, the nightmare continues to grow. Through the ruins of the city, the family has to avoid hundreds of incinerated bodies. There are also radiated children wandering through the middle of Hiroshima trying to find their families.

The hardest scene comes when a small child goes toward his brother, and is incapable to recognize him immediately, bringing up personal questions as to the burnt body of the child. Black Rain is one of the bleakest and most hopeless films ever made, but what kind of hope can we expect after an atomic bomb?

1. Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959)

Taking again Yoshishige’s theory of the impossibility of a Hiroshima recreation, we see a discussion about the issue in the opening sequence of Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour. She (Emmanuelle Riva), a French actress filming in Hiroshima, tells He (Eiji Okada) about the many Hiroshima spaces of memory that she had seen; all the museums, the hospitals, the films, the rests of the houses, every living piece of Hiroshima. He always answers in the same way: “You haven’t seen nothing in Hiroshima, nothing”.

In one of the most beautiful first sequences on film, Resnais instigates a discussion he couldn’t avoid after his previous film. In Night and Fog, Resnais made one the most powerful films ever created about the Nazi camps. He was then asked to make something similar in Hiroshima, but he felt it was impossible.

Was he able to picture the real horror of the camps? Is it enough to make a recreation, to place the camera out in front of the ruins? Does it have any point in front of this horror? These questions arise as She continues to tell He about what she saw.

The film evolves in one of the most complex love tales of cinema history. He and She find it harder and harder to reveal, or even reveal to themselves, what they want from each other. Once we find out about her past lover, a German soldier who died in the war, the audience and the characters are more confused.

It’s almost an impossible task to make a film about a bombing that tells us about love at the same time, but Resnais is successful in this regard. In the end, love is the first thing that broke with the war. The total lack of love and sense is what can make an atomic bomb to fall.

Resnais’ masterpiece stands as one the richest and more complex analysis about the Hiroshima tragedy, and he creates it pointing in different directions, but not directly to the issue. It’s a movie about Hiroshima, but also a film about how to make a film about it.

Author Bio: Héctor Oyarzún is a film student in the Valparaíso University of Chile.Since he was a kid his most important occupation is watching films. He also likes punk music and playing guitar.