8. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (Sergio Leone, 1966)

Sergio Leone makes it hard for us to pick a magnus opus from his films. Once Upon a Time in the West and Once Upon a Time in America could easily be ranked just as high in the list. Yet, it is the final installment of The Dollars Trilogy that sweeps all glory.

Two men ally themselves to find gold buried in a cemetery, before a third reaches it. A particular sequence stands out in the movie, a set piece that depicts Union troops trying to storm Confederates. The main characters intervene in the conflict, changing the world around them, something almost reminiscent of a medieval knight tale. Ironically, the characters must overcome this blood bath to get to their goal: a cemetery.

Leone chose to shoot his film in Spanish landscapes, having them doubled as America. The landscapes are arid and unforgiving, surpassed only by the characters that inhabit them. His is a brutal depiction of the Wild West, a place governed by the law of the cunning and the violent.

The climax of the movie remains one of the best scenes in cinema history, featuring the trademark style directors like Quentin Tarantino would employ in their own films.

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly is the quintessential Spaghetti Western and one of the most palatable epics ever made.

7. Gone With The Wind (Victor Fleming, George Cukor, Sam Wood, 1939)

The definitive Hollywood epic, Gone With The Wind tells the classic story of love in times of war.

The romance between Scarlett and Rhett is among the most interesting and controversial in film. The characters are fueled by desire, duty, and lust. They provide us with a whirlwind of emotions, all unraveling with the Civil War as their background.

Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh give the performances of a lifetime. David O. Selznick, a legend in Hollywood at the time, produced the movie. He already had films such as Anna Karenina and A Tale of Two Cities under his belt, and went on to produce Hitchcock’s Rebecca, winning Best Picture at the Oscars for a second time.

Critics have torn the movie apart over the years. It has been criticized for ignoring slavery and segregation, while defending the South’s traditional values. It has even been charged with allusions to the Ku Klux Klan in particular scenes.

Gone with the Wind stands as the golden Hollywood film, the most beautiful and spectacular among melodramas.

6. Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now makes a strong case for the greatest war film ever made.

Adapted from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, it tells the story of a death commando in Vietnam sent to murder an American colonel gone rogue. The characters navigate a river that takes them deeper into the jungle, into the heart of the war, making them as savage as their surroundings.

Coppola’s talent is at its peak when directing the battle sequences. We naturally enjoy the big explosions, the mighty guns, and the stench of testosterone running wild. We love every minute of it until the sequences take a twist. Civilians are in the way. Things get messy. We are suddenly repulsed with what’s happening on screen. No other movie delves as deep into the darkness within us all, the horrors from which war stems.

Like Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, the making of Apocalypse Now is an epic movie on its own. The documentary film Heart of Darkness depicts Coppola’s struggle to make his vision come alive. To give an example, editor Walter Murch worked over two years in post-production to finish it.

Apocalypse Now is a terrifying and eye-opening experience.

5. Fitzcarraldo (Werner Herzog, 1982)

Epics are measurable by the sheer ambition behind them. Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo stretches this statement beyond human limit. Herzog, hailed by Truffaut as one of the most important filmmaker in the world, explores the limits between passion, ambition, and obsession. It reeks of the sacrifice needed to bring a dream alive.

Carlos Fitzcarrald wants the rubber found in an inaccessible part of Peru’s jungles, guarded jealously by roaring rapids. The solution is simple: hoist a ship over a mountain. If he can achieve it, he will build an opera house in the middle of the jungle.

Herzog didn’t use miniatures or any sort of special effects. No, he in fact hoisted a 360-ton ship over a mountain. Needless to say, the production of Fitzcarraldo is legend in the world of film. The ordeal is told in the documentary Burden of Dreams. Herzog wrote his reflections on making the film in his awe-inspiring book: Conquest of the Useless.

Aguirre, The Wrath of God is another Herzog epic (very Conradian) that deserves mention. Popol-Vuh, the band that scored Fitzcarraldo and Nosferatu, collaborated with Herzog once again in this film.

4. Intolerance (D.W. Griffith, 1916)

D.W. Griffith is cinema’s greatest pioneer. His commandment of editing, particularly of intercutting, has earned him the title as one of the fathers of the medium.

Griffith got a lot of backlash after producing his most famous film, Birth of a Nation. He was criticized for racism and praising the Ku Klux Klan. People even rioted to ban the film. This inspired Griffith to create his most ambitious dream, Intolerance.

The film consists of four storylines spanning over 2500 years of history: the fall of Babylon, the crucifixion of Christ, St. Bartholomew’s massacre in France, and one set in modern day America (at that time of course). They are all linked by Intolerance’s ravaging of humanity, or, as its title says, Love’s Struggle Throughout The Ages.

It was a mammoth production. The gigantic sets give the movie the scale dreamt by Griffith (there is even a homage to them in the videogame L.A. Noire). Extras delved so deep into their roles, they almost killed each other.

Intolerance is one of the greatest movies of the Silent Era. It’s a film to be experienced like a piece of music, to be compared with mankind’s greatest artistic achievements.

3. Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa, 1954)

Seven Samurai has been widely called Akira Kurosawa’s greatest film (a very disputed title). Its epic battle sequences paired with unequaled storytelling definitely make it one of his most enjoyable.

A group of farmers seek the help of seven samurai to defend their village from bandit raids. Nowadays, this is a familiar action movie plot (the team assembled to fight evil). Western movies owe so much to Kurosawa.

Seven Samurai is a tale of duty, interestingly criticizing the ideal at the same time. The haunting final shot lingers in our minds long after the movie is over. The burying wind almost escorts us out of the theatre, and makes us look at society just a little differently. Roger Ebert notes something very interesting: After Seven Samurai, Kurosawa started making very pro-individual films (best exemplified in Ikiru).

Kurosawa is not only a titan among directors, but he is also one of the best writers that ever lived, standing right alongside Ingmar Bergman in that regard. His devotion to themes and characters paved the road for so many filmmakers after him.

2. Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962)

This is David Lean’s masterpiece. Enough said. The poetry behind every shot, every cut, and every facial expression is outstanding.

T.E. Lawrence is sent by the British army to operate in the Arab Peninsula in World War I. His character is among the most complex ever captured on film. Peter O’Toole gives a once in a lifetime performance, he is able to express Lawrence’s struggle for identity in a single stare.

Lean is at the top of his game. There is a cut that stands out above all others. Once Lawrence is assigned his mission, he lights a match and stares straight into the flame. “It is recognized that you have a funny sense of fun,” says Dryden, the commanding officer. Lawrence blows out the match and we smash cut into the red furnace of the desert. This is one of the most famous cuts in film history, and with good reason.

Lawrence of Arabia is magnificent for its spectacle and depth. It is a well of inspiration for any artist. So why isn’t it number one in our list?

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick ,1968)

2001 is not only the best epic film around; it makes a strong case for the best movie ever created.

“Let’s make a really good science fiction film”, said Stanley Kubrick to Arthur C. Clarke before writing the screenplay. And they did. Their imagination is boundless, as they tell the story of human evolution before the eyes of the cosmos.

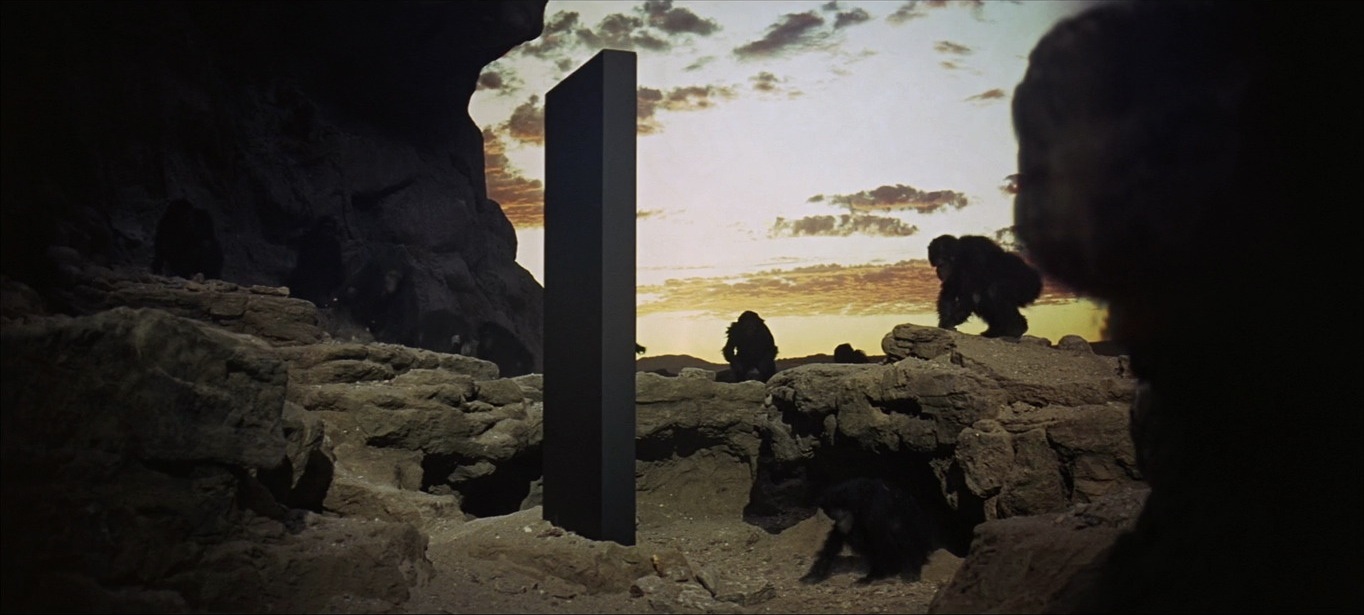

It opens at the dawn of man. We are pathetic, foraging for food in an arid landscape, not intelligent enough to even notice the abundance of delicious meat around us. Then, the monolith, one of the emblems of cinematic history, appears. Suddenly, we not only know how to kill animals around us for survival, but each other to ensure it. This pattern marks 2001, as humanity follows the monoliths like breadcrumbs across the solar system, into what might be our magnificent and terrifying destiny.

So what are the monoliths? No one knows. Maybe aliens. Maybe divine intervention. Us? Kubrick wisely piles this question up with so many more the film offers unanswered.

Of course, the character that stands out of the entire film is the ship’s computer, HAL. More than simply a villain, HAL is a scared being, forced by our own evil to question himself and those around him.

Pink Floyd turned down an offer to perform music for the film. Upon watching it, they devised one of their most famous songs, Echoes, to synchronize with the last part of the film (Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite). You can find this version on YouTube.

2001 is a melody, a poem that can be re-experienced time and time again. Something new will always stands out, either of the film or of yourself. It is a piece to savor for the brilliance of its ideas and the melodious emotions that beat in every frame.

Author Bio: Santiago Sánchez is a young Mexican filmmaker and fiction literary writer. He is very fond of nature documentaries, particularly those of Sir David Attenborough, and hopes to capture the magnificent poetry of our planet. He also enjoys several cups of black coffee in the mornings, and watching Barcelona football games in the afternoon.