8. Triumph of the Will (1935)

It’s a Propaganda legendary documentary that chronicles the 1934 Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg. Hitler was the uncredited producer behind the curtain. Innovative techniques for the time like aerial photography, long focus lenses and a revolutionary use of music and cinematography made Triumph of the Will one of the greatest films ever made.

There is no narration of the story, but there are endless speeches delivered to excited crowds by the most important Nazi leaders, including Hitler himself. The film was conceived as a gift to upcoming generations, telling them about the rise of the Third Reich.

It starts with a propagandist prologue over a grey background, followed by four segments recording each day of the Congress. It doesn’t contain antisemitic rhetoric but instead tries to present Hitler and his gang as Jesus and his disciples. Everything that Hitler says or does is presented in a Messianic atmosphere. Public showings of this documentary are forbidden in Germany due to denazification laws.

Like any other event that has to do with Hitler, this film shows a misinterpretation of the Will to Power. When the Triumph of the Will is accomplished, the one who once had the Will, now will have the Power. But Strength and Power are different concepts and therefore different things.

Anyway, thumbs up for those aerial shots.

7. Fight Club (1999)

I know we’re breaking the first and the second rule of fight club, but trust me…we have to. Fight Club is a modern day cult film with a serious impact in popular culture. It was barely noticed during its first release but obviously kept building its number of loyal fans.

Based on the novel with the same name by Chuck Palahniuk, starring some of the most talented pretty faces of Hollywood, Fight Club presents the most powerful cult of violence and nihilism in the history of cinema since A Clockwork Orange.

Edward Norton plays an unnamed white collar insomniac who attends various support groups at night, pretending to be a fellow victim. There he meets Marla, a Xanax-addicted cute disaster, who’s also a fake attendee just like him. His life changes dramatically when he meets Tyler Durden, a self proclaimed Übermensch, who has his own personal values and morality, totally contradictory to the nameless protagonist.

He and Tyler begin organizing all-male bare knuckle fights. Eventually the nameless narrator realizes that Tyler’s pattern is becoming more dangerous every day. He tries to stop, but this case is more complicated than he thought.

If you take care to notice all the details of this movie, the ending may not come as a big surprise. The philosophical concept clearly explored through the film is the Übermensch, the new man who boldly creates beyond himself, disdaining society’s morality, and trusting only his own moral views and values. The clash between Master and Slave Morality can occur within one single person and in one single mind.

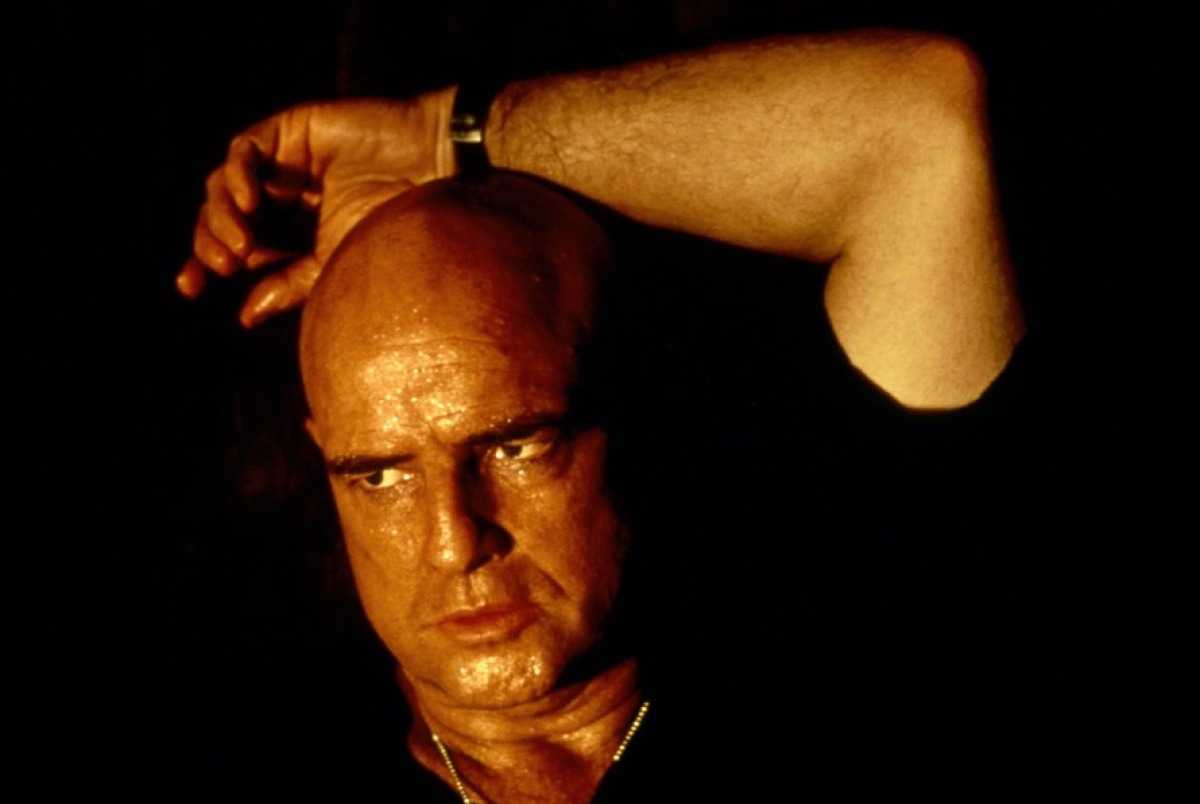

6. Apocalypse Now (1979)

153 minutes of great music, nice shots and great acting. After some initial issues, such as the legendary Marlon Brando being totally unprepared when he first appeared on the set, or the poor critical reception upon the film’s release (although it was burdened with glorious awards…but those were different times), Apocalypse Now is today a cult film praised by critics and casual viewers alike.

It tells the story of an American soldier, captain Benjamin Willard, who is sent on a mission in Cambodia to assassinate the renegade Colonel Walter Kurtz. This story takes place during the Vietnam War. The Birth of Tragedy is the philosophical concept that expands and develops slowly throughout the film.

Like the ancient Greeks, modern spectators need to witness the abyss of human suffering to understand their own purpose and the true meaning of life. But this film complicates such an idea, since the viewers who seek meaning from the film will find only characters who likewise desperately search for some meaning to their existence.

Captain Benjamin Willard is essentially a loser who believes that this mission may be the one that will give purpose to his meaningless life. Colonel Walter Kurtz, formerly a highly-decorated Special Forces officer, has gone mad pretending to be the king of some small Cambodian tribe.

The men are two sides of a coin. An ex-Apollo who doesn’t enjoy being a hero anymore and wishes he could be a Dionysus, and, on the other side, a life-long Dionysus struggling to sit on Apollo’s throne. It’s all about the beautiful intellectual dichotomy between Dionysus and Apollo, constantly gaining and losing ground against each other. Either one is meaningless without the presence of the other.

This movie was highly influenced by Werner Herzog’s masterpiece Aguirre, the Wrath of God.

5. Citizen Kane (1941)

Considered by moviegoers, movie lovers, film critics, filmmakers, and so on to be the greatest film of all time (although of course, everything is relative), Citizen Kane employed innovative techniques in editing, storytelling and camera movement. The film has earned tremendous respect mainly due to Orson Welles’s young age at the time that he co-wrote, directed and edited the film.

The key word is Rosebud. It’s the last word coming out of Charles Foster Kane’s mouth at the moment that he dies alone in his mansion, Xanadu. A group of reporters start digging into his past to find the meaning of the last word. They meet people who knew Charles Foster Kane from his youth, and through flashbacks we explore the past life of the richest man in the USA.

After his poor but sweet childhood, he becomes more and more rich and powerful, beginning in his early twenties. Thus he ends up losing the grand idealism he held at the beginning of the film, and he becomes an American dream come true. But where there is a great rise, a fall is sure to follow. At the end, while alone in his deathbed holding a snow globe, he only needs Rosebud near him.

Philosophically, the film shows the golden point where Will to Power meets Perspectivism. This may be the reason why it got one of the best screenplays ever. (This is not relative; it is absolute.) Citizen Kane’s rise is guided by his Will to Power derived from his Master Morality. While on the top of the world, his Perspectivism arises.

There is no objective truth. He is like a God from the perspective of the others, but from his own perspective… he doesn’t know who he is anymore. The collective values may have no significant meaning in comparison to one’s will. So, living in a house that most people could only dream of, burdened with a rock star reputation, Charles Foster Kane finds that Rosebud is the only thing that he desires.

4. Dogville (2003)

The first film of Lars Von Trier’s project USA – Land of Opportunities takes place in a minimalist stage, inspired by Bertolt Brecht’s epic theatre. Dogville is composed of nine chapters and one prologue.

It tells the story of Grace, a beautiful young woman running from mobsters who takes shelter in a small town in Colorado named Dogville. Tom, the spokesman of the town, encourages the little isolated community to hide Grace from the mobsters. In return, she will work for them. Everything seems to be fine.

But when the sheriff comes to town with a “missing person” poster of Grace, the community wants a better deal from Grace in exchange for continuing to hide her. And when the sheriff comes once again with a wanted poster, they turn Grace into a slave and keep hiding her. Yet Grace hides a deadly secret, so it turns out not to have been such a great idea to mess with her.

The point of the film, as Lars personally claimed, is that “evil can arise anywhere as long as the situation is right.” In other words, the point of the film is the basic philosophy of Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil and On the Genealogy of Morality.

Once again we see the Master-Slave Morality. Every man should be guided by his inner laws, but when masters and slaves invert, there will be heavy dramatic consequences because they are not respecting their inner laws.

Grace first appears in the film as master and the Dogville townsfolk as “slaves”. After changing places, they finally reveal what they truly are.

3. The Sacrifice (1986)

The last film written and directed by Andrei Tarkovsky was conceived while the master was still in the Soviet Union. He was diagnosed with cancer during the editing process in 1985, but he had been unaware of his condition while writing and shooting the film; the film’s main theme regarding death is in fact coincidental. Anatoly Solonitsyn was originally chose to be the lead actor, but he had died from cancer in 1982.

Alexander, a journalist, former actor and philosopher plants a tree with his son, “Little Man,” who is temporarily mute. He tells the son the legend of Ioann Kolov, pupil of an Orthodox monk named Pamve, who was ordered by his master to climb a mountain every day, to water a dead tree he had planted until the tree came back to life, which, after three years, it did.

At this point, Otto, a part-time postman and also a philosopher, arrives with a birthday postcard for Alexander. Alexander spontaneously informs his friend that his relationship with God is nonexistent. After Otto leaves, Alexander’s wife Adelaide, an actress, and the family doctor, Victor, come to take the Alexander and his son home. (Alexander’s home is a beautiful house which was burnt down twice during the shooting of the film.)

Everyone celebrates Alexander’s birthday. When the party ends, a news program announces the beginning of a nuclear war between political superpowers. Alexander desperately prays to God, offering everything he owns in exchange for God preventing the war. Otto tells him that he may save the world if, that night, he visits the maid Maria, whom Otto believes to be a witch.

Alexander visits Maria, then awakes the next morning to find that everything appears quiet and peaceful. He then tricks his family and friends into leaving the house on a walk and, while they are out, he sets fire to his beautiful home. An ambulance suddenly appears, seemingly from nowhere, and takes him away.

Then we have the final scene: As Maria rides away on her bicycle, she notices Little Man, who waters the tree he and Alexander had planted the previous day and says, “In the beginning was the Word. Why is that, Papa?” The boy is not mute anymore. Tarkovsky dedicated The Sacrifice to his own son.

The most confusing detail of the film is the strange sequence of events when Alexander prays to God and spends a night with the witch. The world was saved, but to whom should we attribute this miracle? Otto mentions Nietzsche’s dwarf at the beginning of the film. “Everything straight lies,” says the dwarf to Zarathustra, adding that “Time itself is a circle.” The legend of Kolov is not an accidental detail. It presents the Eternal Return.

So Alexander is offering a gift, the ultimate gift to humanity through his beyond-human sacrifice. The auteur Tarkovsky presents the Eternal Recurrence as an antidote to Nihilism.

The entire film remains open to profound interpretation. Andrei was likely crafting a story that reflected his own confusion and insecurity. Perhaps he considered Eternal Return to be a concept that unified all of his films. Tarkovsky contemplates the man who makes something beyond himself. Ultimately, the outcome is the same whether the cause was God or the witch.

2. Napoleon (1927)

This epic silent French masterpiece by Abel Gance tells the story of Napoleon from his early years until the invasion of Italy, with Napoleon leading French border army. It is an intense, six hour biopic which is very well known for its innovative techniques and for a fluidly-moving camera in a time when most camera shots were static.

The film displays impressive use of fast cutting, hand held camera, POV shots, multiple camera setups, superimposition, multiple exposure, underwater camera, and other techniques, all culminating in the final twenty-minute triptych sequence. Techniques used in Napoleon heavily influenced the French New Wave.

Napoleon was supposed to be only the first part of a six-part project, but after the director shut down this plan due to its high budgetary demands, only this single film saw completion.

The film begins with a young Napoleon attending military school, managing a snowball fight like a true commander, yet being insulted by other boys. Since this first scene, the audience not only sees Napoleon’s Will to Power but is also emotionally engaged in the experience.

Ten years latter, during French Revolution, Napoleon serves as a young army lieutenant on the outskirts of battle. He returns to his parents’ house in Corsica. After some true political danger, he flees to bring his family to France. While serving as an officer of artillery in Siege of Toulon, his genius talent for commanding earns him a promotion to brigadier general.

Jealous, less-talented revolutionaries imprison him, but the prison cannot hold him for long. Napoleon promptly escapes from prison and begins forming strategies to invade Italy. He marries Josephine and rises through the military ranks to Commander-in-Chief of the Army of the Interior; all the while, he maintains his plan of invading Italy.

There are no spoiler alerts, since one may read the history of Napoleon and the French Revolution in any elementary textbook.

Napoleon is probably the most typical figure who manifests Nietzsche’s Will to Power. In this marvelous film, Napoleon is an energetic presence whose very appearance proclaims “I deserve my prestige!”

Napoleon’s lifelong Will to Power, beginning in his childhood, eventually earns him the Power he so desires.

1. The Turin Horse (2011)

This is the last film of the living legend Bela Tarr, after which he announced that he would quit filmmaking. This black and white masterwork is shot entirely in 30 long takes which show the repetitive daily life of a horse, his owner, and the owner’s daughter.

The opening credits tell the story that, on January the 3rd 1889, Nietzsche witnessed the brutal whipping of a horse and supposedly suffered a mental breakdown as a result. Nobody knows how much of the story is true or fictitious.

This film never had a conventional screenplay. The financial backers received only a short prose piece written by Krasznahorkai instead of any more detailed document.

Unlike all the other films in this list, Turin Horse is not just influenced by Nietzsche’s principal philosophy, but it portrays the cause of this tremendous philosophy: the heaviness of human existence. The repetitive shots are real life shots. A man, his daughter, and their horse struggling to survive in a world that has much in common with a post-apocalyptic world.

The Eternal Return in here is not something strange or inhuman. The nihilism comes from some simple everyday characters. There is no barrier between the world of the characters and that of the audience. What you see in the film is what you may see everyday: real outsiders, not a bunch of hipsters pretending to be misunderstood.

The visitor gives to the girl a copy of the Anti-Bible. Expanding Nietzsche’s thoughts the man doesn’t blame only God for humanity falling, but both God and humans.

Bela Tarr said that the visitor who comes to the man and daughter was “a sort of Nietzschean shadow.” The filmmaker, who always wanted to be a philosopher and was a long life detractor of classical storytelling, considered Turin Horse a simple anti-creation story.

Bio: Lediona Kasapi is an independent filmmaker who thinks that a good film is one that deserves to be watched inside an art gallery.