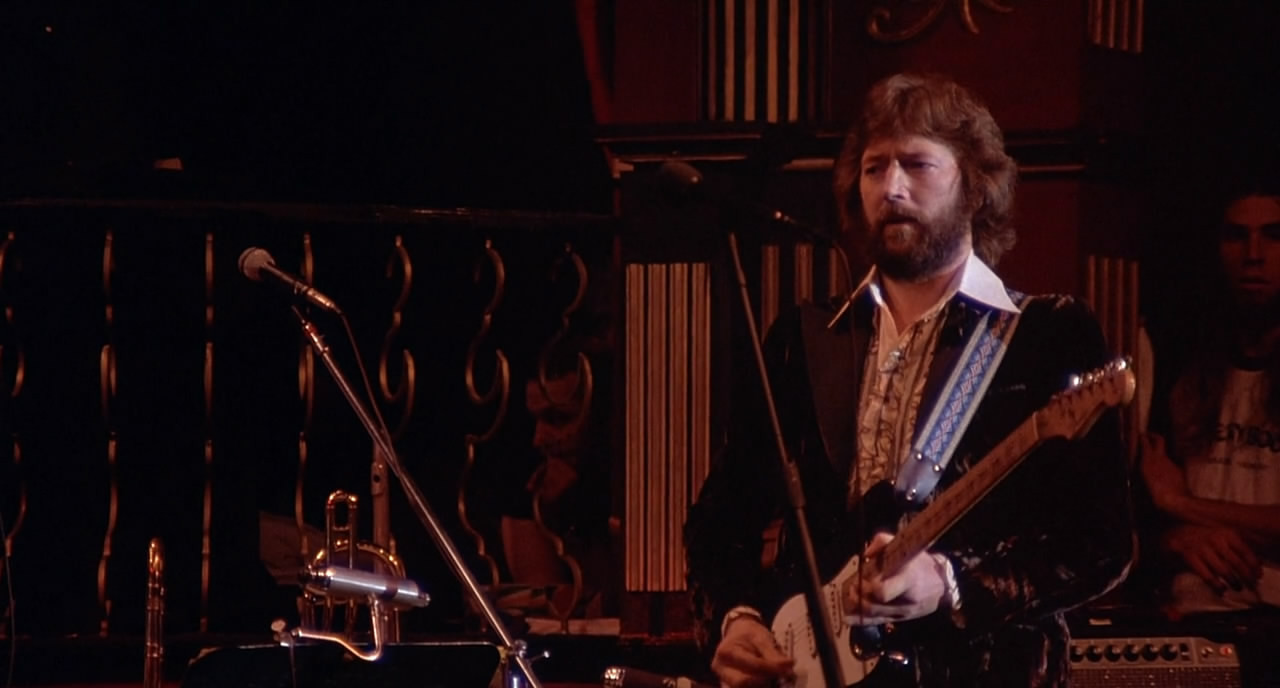

8. The Last Waltz (1978, Martin Scorsese)

The all-star farewell show for The Band came during the depths of the industry’s (and the filmmaker’s) white line obsessions – a lump of blow had to be optically removed from Neil Young’s nostril for “Helpless,” but the talent, including Dylan, Van Morrison, Muddy Waters, Joni Mitchell, and the act’s old boss Ronnie Hawkins, still shines; so does the music.

Shot in the indoor venue of San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom, the sharp photography is closer to that of a polished studio production rather than a point-and-zoom open-air occasion (e.g. Woodstock). Even if the cameras unduly favored Band guitarist and Scorsese pal Robbie Robertson, there’s no neglecting the brilliant contributions of Garth Hudson or the late Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Levon Helm. Their backstage recollections of life on the road, notably Hawkins’ promise of “more pussy than Frank Sinatry,” are worth a movie all to themselves.

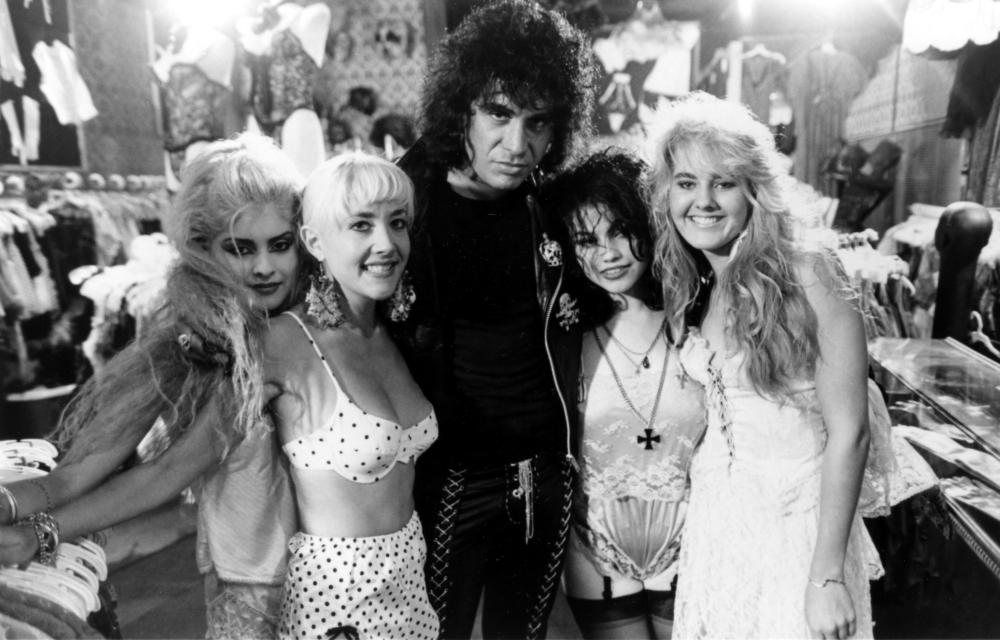

7. Decline of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years (1988, Penelope Spheeris)

While focused on the ephemeral LA hair-metal acts of the 1980s (Odin? Cryptic Slaughter?), there are also some illuminating interviews with veterans like Alice Cooper, Motörhead’s Lemmy, Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley of Kiss, and a relatively lucid Ozzy Osbourne. Bragging about being one of the “Toxic Twins,” a newly clean Steve Tyler is asked, “Are you proud of it?” and has to reflect a little: “Uh…no…”

Plus, the terrifyingly alcoholic poolside conversation with Chris Holmes of Wasp. Equally useful as a rejoinder to anti-rock religious zealots and besotted wannabes – notwithstanding all the sound and fury they convey on stage, most of these people are really pretty harmless.

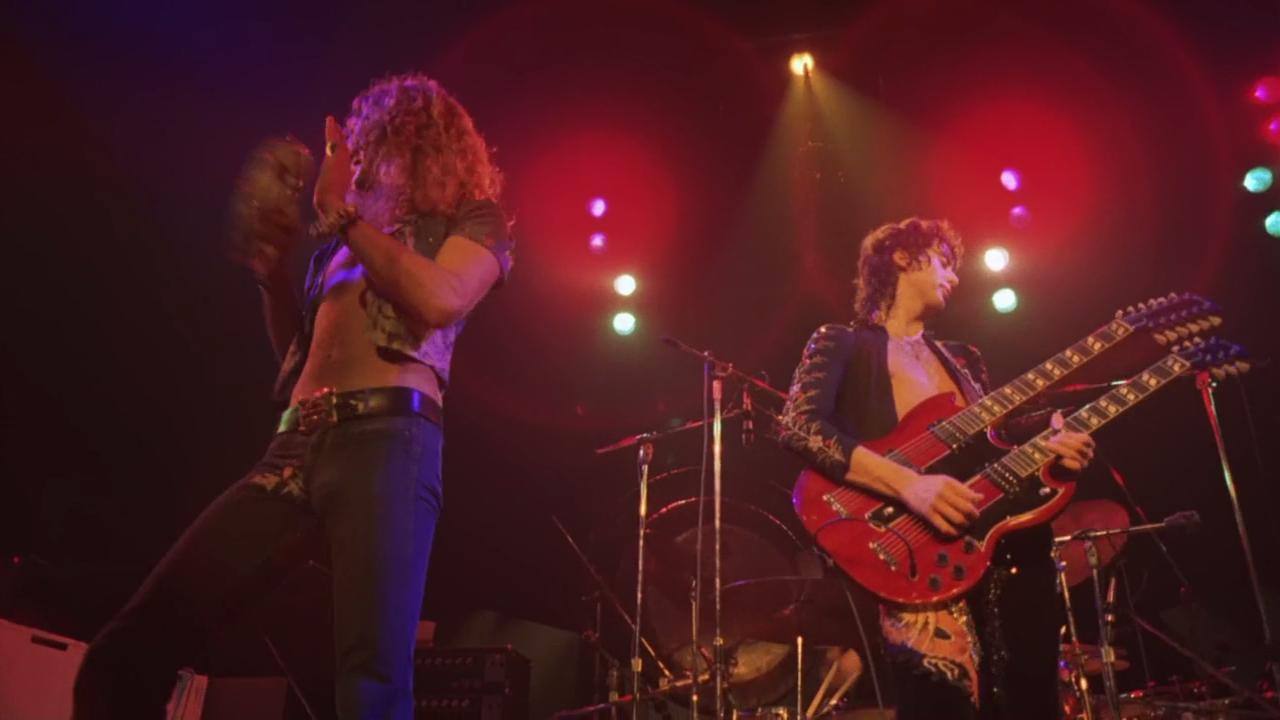

6. The Song Remains the Same (1976, Peter Clifton, Joe Massot)

Though Led Zeppelin subsequently presented superior live gigs on video, the sheer bombast of their 1973 Madison Square Garden concerts (some close-ups were actually filmed at Shepperton Studios the following year) made this a long time fan fave. Intercut with news of a still-unsolved 200,000 dollar cash robbery from the band’s hotel and elaborate “fantasy sequences” of the individual members, this, incorporating the half-hour “Dazed and Confused” and the fifteen-minute “Moby Dick” drum solo, is what rock ‘n’ roll excess is all about.

Remember to say, “Show us your eyes, Jimmy,” just before Page turns to the camera during his eerie solo intro. Cameraman Ernie Day, oddly, is the missing link between Led Zeppelin and David Lean – he also shot Lawrence of Arabia. Most poignant moment: Robert Plant introducing “Stairway to Heaven” over a NYC skyline, complete with Twin Towers: “I think this is a song of hope…”

5. Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii (1972, Adrian Maben)

A perfect complement to the hypnotic trippiness of Floyd’s sound, this classy, cerebral doc features the foursome making what will become Dark Side of the Moon in London and rocking out in the eponymous Roman ruin, with ancient mosaics and architecture forming an imaginative backdrop to epic instrumentals like “One of These Days I’m Going to Cut You Into Little Pieces” and “Set the Controls For the Heart of the Sun.”

The slow dolly shots of the “Echoes” performance – simple idea, spellbinding effect – will nearly melt your brain. Interviews with Roger Waters, David Gilmour, Nick Mason and Rick Wright, steeped in prog-rock profundity, are in their own way, almost as surreal; Gilmour denies that Floyd is “a drug-orientated group” and Waters holds forth on the impending “great economic collapse,” as if he has the faintest notion of what he’s talking about. Caution: do not attempt to operate heavy machinery while watching.

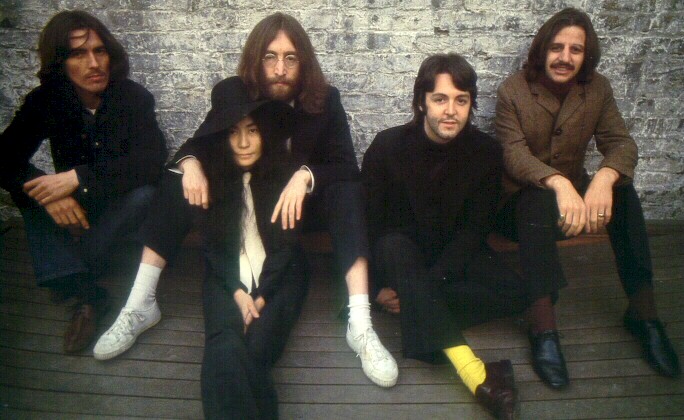

4. Let It Be (1970, Michael Lindsay-Hogg)

By turns fascinating, thrilling, and very sad, this intimate look at the Beatles near the close of their active career showcases some of the Fabs’ loveliest (the rooftop concert) and lowest moments (George plainly fed up with Paul while rehearsing). Invaluable for its glimpses of both the group’s creative processes, in embryonic versions of “Octopus’s Garden” and “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” as well as its inexorable breakup.

Indeed, having to make music while under the cinema verité scrutiny of Lindsay-Hogg’s camera crew likely hastened the Beatles’ disintegration: by this time, they’d long since passed the audition and should have had nothing left to prove. Like Gimme Shelter, Let It Be was initially intended as a flattering treatment of its central figures, but it unintentionally became an embarrassment, on a personal, if not musical level.

The labor-intensive shooting schedule at Twickenham Studios, working on a project only McCartney had much enthusiasm for, made a growing estrangement between the four that much more obvious. Visual and aural outtakes from Let It Be have been widely bootlegged, further revealing the underlying tensions that had crept into Pepperland.

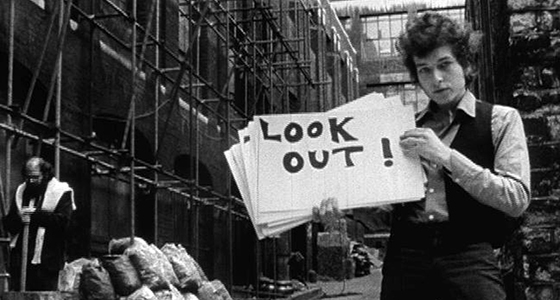

3. Don’t Look Back (1967, D.A. Pennebaker)

Bob Dylan’s enduring stature as a gnomic genius owes as much to this film as to any of his songs or public pronouncements. Never mind his numerous reinventions and departures in the fifty years since – this is how most of us want to think of him. Taken at the peak of his early fame and influence on a landmark British tour with friends like Joan Baez, Allen Ginsberg, and Donovan coming in and out, Dylan’s shown in all his inscrutable, amphetamine-fueled irascibility; his testy exchange with a Time reporter became a defining point in the which-side-are-you-on cultural debates of the period.

Then again, how would you handle it if your switch from folk to rock music had spurred an unprecedented critical controversy, if you were hailed as the voice of your generation, and you were all of twenty-five-years-old? In hindsight (but don’t look back), Dylan, Pennebaker, and Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman may have been creating an early attempt at a calculated media manipulation, the sort of thing that would win Madonna the admiration of po-mo academics two decades later, except with better tunes.

How else to explain something as original and as inimitable as the “Subterranean Homesick Blues” placard sequence, Dylan peeling off the lyrics like cue cards for the world’s most speed-crazed Beat monologue? What kind of rock ‘n’ roll star does that? Much of the picture seems to be about Dylan trying to confuse his analysts and dismiss his detractors, not just with his music, but also through his screen character: a young pop singer determined to defy whatever pigeonhole the establishment and antiestablishment press sought to keep him in, and the very idea of artistic pigeonholes themselves.

2. Woodstock (1970, Michael Wadleigh)

The most memorable performances – Richie Havens, Ten Years After, Santana, Sly and the Family Stone, and of course Jimi Hendrix – would have been enough to make this a classic record of what happened during Three Days of Music, Peace, and Love; we can thank Martin Scorsese for some of the editing magic that distilled a sprawling and often chaotic show into these choice selections.

Like other concert documentaries, Woodstock probably provides a fuller perspective of what went down than anything observed by most of those in the audience of August 1969. Hendrix’s famous Stratocaster reinvention of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” now seen as a key symbol of the event and the era as a whole, was actually played to a crowd that had dwindled to remaining diehards. Multiple split-screen effects heighten the mind-blowing quotient.

It’s the incidental, face-in-the-crowd details of the festival, however, that make this the definitive representation of 60s youth culture. Nothing says more about the era’s social divides, for example, than the interview with the genial sanitation worker who talks about his two sons, one there at Woodstock, and one serving in Vietnam. Whereas the Baby Boomer mythology around themselves and their entertainments can be awfully self-congratulatory, the bucolic fields of Yasgur’s Farm recorded for posterity here prove that some of that idealization is fully justified. PS: Stay away from the brown acid.

1. Gimme Shelter (1970, Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Charlotte Zwerin)

Had the Rolling Stones’ 1969 US tour proceeded without major incident, the Maysles brothers would still have captured a remarkably candid portrait of the band playing to crowds of countercultural true believers (the band’s previous American gigs were three transformational years prior), recording parts of Sticky Fingers at Muscle Shoals studios, and living and traveling like the dangerous rock outlaws it’s now hard to remember they ever were.

The first showings of Gimme Shelter, only a few months after the tour, inflamed the Stones’ reputation as harbingers of impending revolution. “Jagger and his henchmen come across as archetypal creeps to me (just as to the young they come across as archetypal demigods),” sniffed arch-conservative critic John Simon.

Keith Richards in Gimme Shelter became the epitome of drugged-out cool, and even the extended shot of Charlie Watts listening to a playback of “Wild Horses” is a virtual advertisement for the blended pleasures of good tracks and heavy dope, or vice-versa. Meanwhile, if you haven’t heard the black-ass version of “Satisfaction” Jagger sang for these concerts, you’re in for a racially charged treat of Ebonic proportions.

Nevertheless, the climactic Altamont concert, intended as a Woodstock west, and captured here as a hippie Inferno, takes the film into a whole other level of psycho-pharmaceutical intensity: the sight of the Hell’s Angel writhing in a dreadful, lysergic firestorm while the Stones play “Under My Thumb” is enough to put anyone off hallucinogens forever.

Then, the murder of Meredith Hunter just in front of the stage, played and replayed in all its 16-mm horror, took the quintet’s bad-boy image into the far more serious issues of criminal complicity and the dark underside of rock fandom. What began as a tribute to the Rolling Stones’ popularity has ended up as a hard-news study of the moral recklessness and latent violence within the society and the generation they inspired, the movie’s title song taking on a resonance no one foresaw at the outset. Little-known fact: some of the Altamont shots were lensed by a young freelance cameraman named George Lucas.

Author Bio: George Case is the author of several books on Twentieth-Century pop culture, including Out of Our Heads: Rock ‘n’ Roll Before the Drugs Wore Off (2010), Jimmy Page: Magus, Musician, Man (2007), and most recently Calling Dr. Strangelove: The Anatomy and Influence of the Kubrick Masterpiece (2014). His weekly blog, ” and Ideas,” can be found at georgecaseblog.wordpress.com.