8. Cristi Puiu

Cristi Puiu is one of the interesting names from Romanian cinema of the last several years. After Ceausescu’s government, the political scenery of Romania was complex and it had one of the most interesting sudden changes to capitalism. The children raised under Ceausescu’s period grew to tell their versions of it. For some critics, the first example of this new cinema came with Puiu’s first feature “Stuff and Dough” (2001).

We can find most of the elements identified with the movement in Puiu’s work. On his most recognized piece and best work to date, “The Death of Mr. Lazarescu” (2005) the camera style tells as much as the plot with its pseudo-documentary aesthetic, and the austere mise-en-scène describes a part of Romanian society before heading to the main theme of the film. It is only the first effort of “Six Stories from the Outskirts of Bucharest”, a six-part series about different kinds of love in Romania.

All of these visceral and realistic portrayals made the Romanian New Wave win recognition all over the world, and gave the film the “Un Certain Regard” prize from Cannes Film Festival. However, the highest prize was yet to come for Romanian New Wave for a film from a director who is several spots ahead on this list.

7. Martin McDonagh

Martin McDonagh had been placed as one of the major playwrights of his generation, even called the greatest by some critics. He is seen as a polemic figure characterized for his use of violence under light contexts and for his black humor. In one of his many criticized statements, he remarked that he prefers cinema to plays because he has a great respect for the history of cinema, and a slight disrespect for theater.

After trying with a successful shortcut in 2004, his first feature starring Colin Farrell was a success between the critics and at the box office. This blend of humor, crime and violence was received as fresh and make his style available for a much wider audience.

His next film, “Seven Psychopaths” (2012), had similar luck and added a reflection about his incursion on cinema. Even if he rejected this game later, calling the film “too meta”, the exploration of the new field is there and shows that McDonagh doesn’t want to take to the screen a copy of his plays.

6. Makoto Shinkai

Makoto Shinkai is one of the rare cases where the trademarks and style of the director seem to be completely developed since his first feature film. In “The Place Promised in Our Early Days” (2004), we can spot his main themes and animation motives. The relationship between love and friendship and its evolution through time is installed, as is the perfectionist animation, with special care on landscapes and skies.

On his prettiest film to date, “5 Centimeters Per Second” (2007), all these elements evolved and gained even more complexity. He also went deep with the relationship between characters and technology. The film put him on the world map and made his name popular outside Japan.

Quickly he started to win praise from critics and comparisons with the filmography of Hayao Miyazaki. Shinkai found all this hype exaggerated, and revealed how the influence of Miyazaki on his work was very important, but that he found himself on a lower level. On his latest film, “The Garden of Words” (2013), the level of detail in every frame increased even more, giving every tree and cloth the same precision of the main characters.

The greatest thing about Shinkai is that his greatest work is still yet to come, and his crafted and delicate style can bring us a masterpiece in the future.

5. Derek Cianfrance

With Stan Brakhage as a cinema history professor, he shaped his view about cinema. And if the films of Cianfrance are not close to the experimental approach of the master, his formal approach influenced his narrative and straightforward films. After his very-difficult-to-find debut “Brother Tied” (1998), Cianfrance found it difficult to produce another film.

With a bunch of close friends and two committed actors, Ryan Gosling and Michelle Williams, he made a romantic film that wasn’t what most people expected after seeing the poster and Gosling’s name above the title. With unscripted scenes, the film shows a bleak vision on romantic love.

Cianfrance makes a classically structured film, but with some touches of his different sources and influences. “The Place Beyond the Pines” (2013), had a totally different subject matter, but the cinematography was there, as well as his way of mixing classic elements with some experimentation.

4. Cristian Mungiu

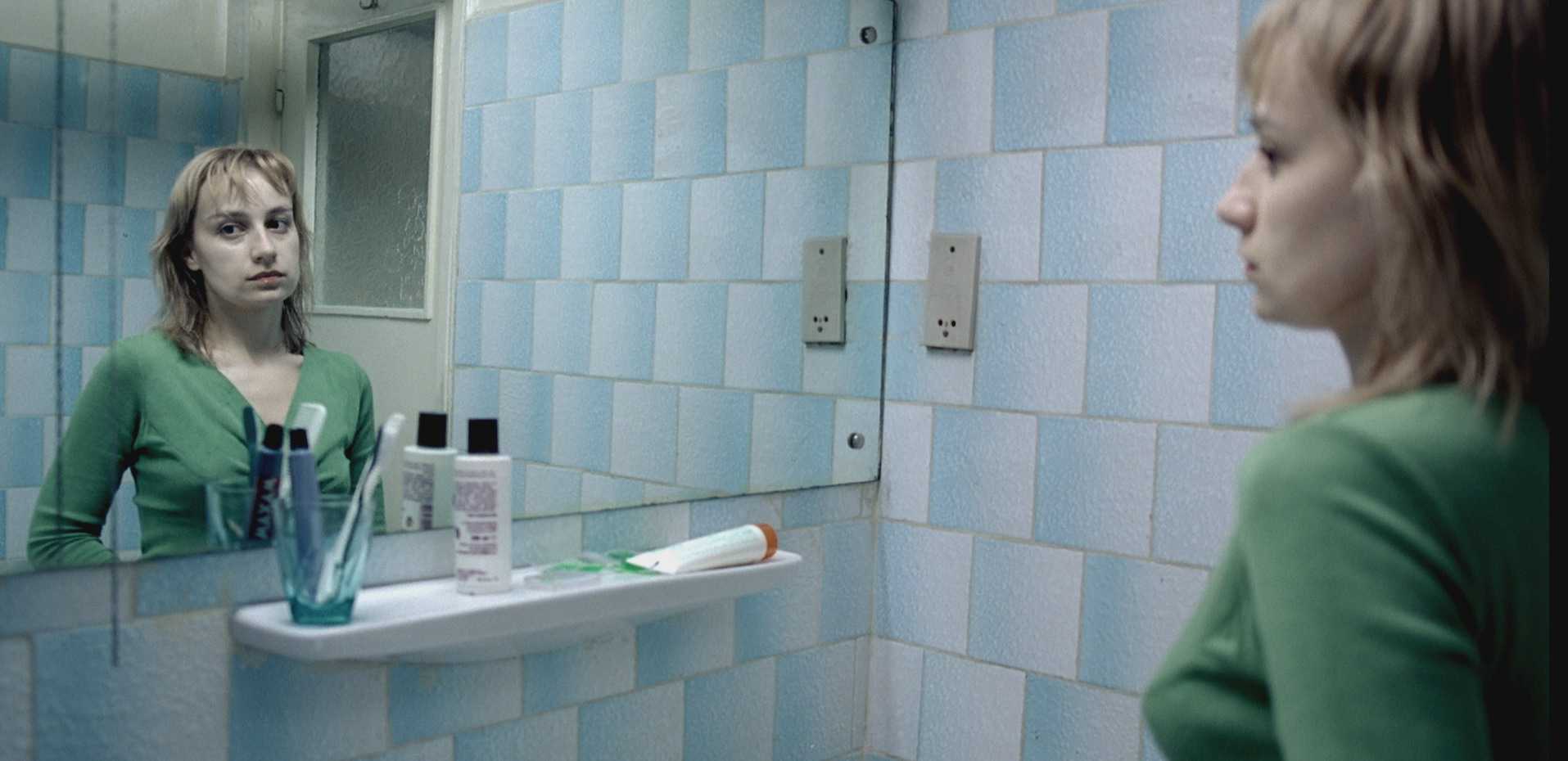

There is a very different approach from the formal aspect between the two Romanian directors on this list and the other directors. Even if the way they treat the camera are opposite (Puiu moving it a lot and Mungiu preferring static shots most of the time), their storytelling is closer on many aspects. Always with a political idea influenced by Ceausescu’s government or what it came next, this films show with rawness the forgotten part of the Romanian population.

With “4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days” (2007), Mungiu took this new-realism to a new level and won the first Palme D’Or for a Romanian filmmaker at the Cannes Film Festival. With a small plot about a woman searching for an illegal abortion during Ceausescu’s last years in power, the crude way that everything is portrayed makes this simple tale a very hard one to view.

At the end of every one of Mugiu’s films we are left with a sense of uncertainty and uneasiness that forces us to give everything some thought. In a time where the realism loses some power, the Romanian New Wave injects some new force to this kind of cinema.

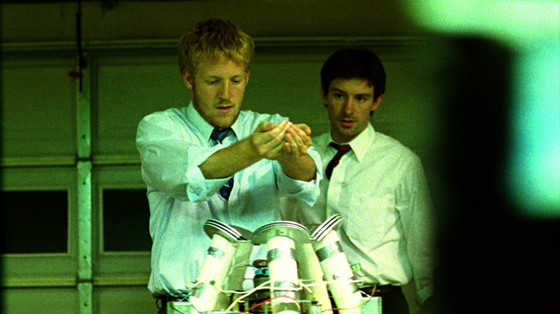

3. Shane Carruth

With only two films to date, Shane Carruth is already famous for delivering some complex and confusing films. From the time travel madness of “Primer” (2004), to the mind controlling parasites of “Upstream Color” (2013), the ideas behind Carruth’s films are real scientific problems. Carruth has a degree in math and has worked on software developing before completing his first feature.

Carruth seems to want total control of his concepts, from the scientific roots of them to the delicate cinematography, and if that wasn’t enough, he also stars in major roles on both films. His next film, “The Modern Ocean”, could easily be his leap to a bigger audience, working for the first time with all-star casting that includes Anne Hathaway and Keanu Reeves.

2. Charlie Kaufman

It seems odd to put a director with only one film to date in the second spot on this list, but Charlie Kaufman’s name had a respected space in cinema before his directorial debut. He is recognized as one of the greatest screenwriters of his time. His debut “Being John Malkovich” (1999), directed by Spike Jonze, was praised as an original plot with an ingenious sense of narrative. In following years he worked again with Jonze, but also with Michel Gondry and George Clooney.

In every film, with different levels of success, the script by Kaufman was always one of the highest points of the film. In 2008 he finally released his first attempt as a director. “Synecdoche, New York” (2008) was highly praised as one of the best films of the decade, and it looked like a more complex version of his previous works.

All the themes and fears expressed in his previous scripts were fully developed and made for one of the most personal films of the last years, a crazy new version of “8½”. At the end of this year we will have the privilege to see his second film, “Anomalisa”, a film that surprised everybody with its trailer and for being the first incursion of the director into stop-motion animation. The level of detail on the characters’ background looks amazing, and we hope that the film stands up to the expectations.

1. Miguel Gomes

Most of the directors on the list are praised for their detailed cinematography and for their general way of treating images. In the case of Miguel Gomes, there hadn’t been a filmmaker with so much experimentation on sound design. In “Our Beloved Month of August” (2008), there is a discussion between the film crew and the boom recorder where he can’t record the proper ambient sound because there is music on every recording.

On “Tabu” (2012), there is also some playing around with ambient sounds. There are some scenes in the jungle where ambience sounds completely quiet, and some interior scenes where you can hear an active jungle.

This is just one of the interesting aspects of this Portuguese director. The violence of colonization and the political background for the European crisis makes his films a fresh uncommon vision for not so widely discussed issues for cinema. His next film, an adaptation of “Arabian Nights” in the Portuguese context, is a monumental 6-hour film worth checking out for everybody with an interest in sound design, or in political films, or in cinema itself.